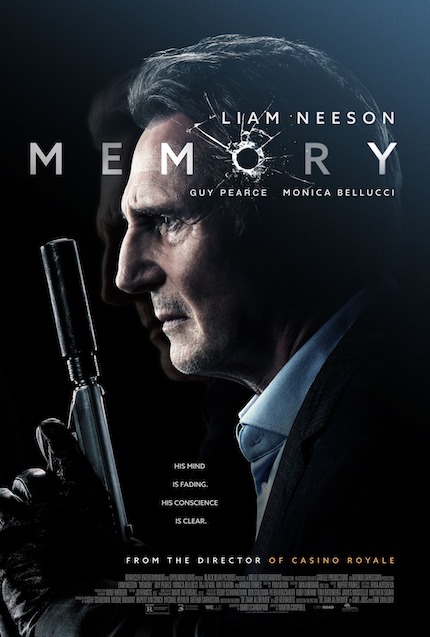

Review: In MEMORY, Liam Neeson Returns to Familiar Action-Hero Mode

Liam Neeson, Guy Pearce and Monica Bellucci star in an action film directed by Martin Campbell.

The return of Martin Campbell, the Brit director who successfully rebooted the James Bond franchise not once but twice (GoldenEye, Casino Royale), on opposite sides of the millennium and gave English-language audiences Antonio Banderas as the title character in The Mark of Zorro, counts as something to both welcome and/or celebrate.

That's especially true after a prolonged absence from the kind of stylish, slick entertainments (2011's headache-inducing Green Lantern misfire notwithstanding) that made Campbell one of Hollywood's go-to directors for more than a decade.

After two middling, modestly budgeted, ultimately disposable efforts (The Protégé, The Foreigner), and now a third, underwhelming film in a row, Memory, a remake of a little-known, barely remembered 2003 Belgian crime-thriller, The Memory of a Killer (aka The Alzheimer Case), it’s fair to wonder if Campbell has lost permanently whatever edge he once had as a mainstream filmmaker.

Filmed during the pandemic in Bulgaria (semi-convincingly doubling for El Paso, Texas), Memory pairs Campbell with genre stalwart Liam Neeson as Alex Lewis, a longtime hitman with an unsurprising set of very special skills and an inflexible moral code that defines not just what he does, but who he thinks he is. It’s a code, of course, the corrupt Powers-That-Be will eventually try to compel a reluctant Lewis to ignore.

Despite Lewis’s graying temples, deliberate gait, and AARP membership, he’s still an efficient, ruthless killing machine, dispatching henchmen half his age without breaking a sweat or chipping a well-manicured nail. There’s just one problem: Lewis suffers from dementia-related memory problems. Frequent pill-popping seems to alleviate the worst of the symptoms, though only temporarily. Given the need to know where he is, what he’s doing, and when he’s doing it, Lewis’s memory issues pose a serious risk to his short-term and long-term longevity.

An early contract kill bears this out as Lewis forgets his car keys at the most inopportune time (i.e., moments after leaving a garroted victim behind). Neeson grounds the pulp conceit around Lewis’ deficits in a typically naturalistic, realistic performance, treating Lewis and the film that surrounds him with the seriousness and gravitas Neeson brings to practically every performance regardless of the quality (or lack thereof) of the material. Even when Neeson’s coasting, as in the recent Blacklight, a disposable entry that came and went just two months ago, he’s imbuing his performances with a rawness, emotionality, and authenticity atypical for an action-first, character-second genre.

Lewis confronts a lifetime of bad choices head on when he refuses to complete his latest contract, the murder of a 13-year-old Mexican girl, Beatriz Leon (Mia Sanchez), who knows far too much about a cross-border human trafficking ring. In turn, Lewis's decision to spare Beatriz makes him a (hit) man marked for elimination by said human trafficking ring. The paint-by-numbers story also involves a duplicitous real-estate mogul, Davana Sealman (Monica Bellucci, a welcome sight, if predictably underused), her sexually deviant fail-son, Randy (Josh Tayler), and the FBI head of a cross-border task force, Vincent Serra (Guy Pearce), pursuing Lewis who eventually finds himself facing a dilemma of his own.

As an official representative of law and order, Serra remains duty-bound to stop Lewis before he kills and kills again. On a personal level, however, Serra increasingly sees Lewis, if not as an outright ally, then as a useful instrument in bringing down anyone associated with the human trafficking ring.

Serra also represents a reactionary point-of-view embedded in the genre’s tropes and conventions, the police or federal officer hamstrung by the criminal justice system and its inherent bureaucracy who eventually relents and adopts the idea that a little extra-judicial justice is what the world — or in this case, the perpetually turbulent U.S.-Mexican border — badly needs to restore an idealized social and political order. Lewis doesn’t so much represent Serra’s opposite as much as his brute-force double, doing what Serra has not so secretly wanted to do without the fear or possibility of professional or personal consequences.

Ultimately, though, it’s hard to escape the feeling that Memory, Neeson and Pearce’s committed performances aside, all too often falls into surprise-free, generic, formulaic filmmaking, the result, at least in part, to Dario Scardapane's adaptation of the Belgian original and the underlying source novel. Campbell directs the handful of action scenes with a directness and briskness that reflects his general competence as a filmmaker.

Those same scenes, though, never stand out, suggesting Campbell took the assignment more out of necessity or need than actual interest in directing this particular screenplay or working with Neeson. Given Neeson’s seeming inability to deliver an uncommitted or unpersuasive performance, Memory comes as close to watchable as anything in Neeson’s oeuvre over the last decade (Silence excepted).

Memory opens Friday, April 29, only in movie theaters, via Open Road Films. Visit the official site for more information.