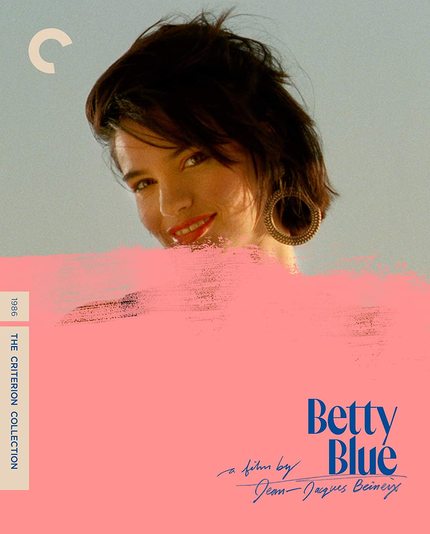

Blu-ray Review: Criterion's Revealing BETTY BLUE

Sex, skin, color and texture command central focus in this restored and deeply flawed French arthouse drama.

Fair warning... In the interest of taking a more meaningful look, this critique contains references (non-specific) to the ending and various story points of Betty Blue and other films.

The central extremism of the Freudian Madonna (mother)/whore dichotomy can, in theory, be a narratively handy thing. But that’s really only when its inherent falsehood and tendency to lack any middle ground whatsoever is critically explored. The complex is an age-old thing, detailing the psychological deficiency in which a man is only able to view women as either saintly matrons or debased sex objects.

In film, however, it’s far more common to find the mother/whore theory taken at face value, almost as though the filmmaker himself is suffering the complex right before our eyes. A solid such case for consideration is director Jean-Jacques Beineix’s 1986 wandering opus, Betty Blue.

For Beineix, obviously a filmmaker of literal vision if not narrative discipline, the mother/whore dichotomy becomes the embodiment of his third feature film’s title character. With an indulgent running time that borders on the ridiculous- exactly three hours- one would think that Beineix could find the time to go in between or even beyond these two constructed poles of female self.

Alas, no. An ace shooter he may be (Those sunsets! The way the neon reflects on the wet street!), but so too is any given male porn star. Betty Blue is content to stand back and watch as Betty herself slowly unravels in her inability to ever truly embody either the mother (someone to settle down and have children with) nor the whore (an uninhibited and insatiable sex goddess) that her committed lover wants. (She would be first the latter, then the former, natch).

This not only shortchanges an entire gender (albeit one that has become all but accustomed to it), it forsakes a prime tenet of cinema. Which is, that in and around the inherent directness of the medium- a central strength, to be sure- there is the potential for subtle observations- essential grace notes that can be everything- lurking in the cracks, hovering on the fringes. Such instances are not altogether absent in Betty Blue, they’re just absent completely for her. (Cue another nude scene.)

When Betty (Béatrice Dalle, never holding back), a young girl of nineteen, becomes the lover of the slightly older, centered and sensitive handyman, Zorg (Jean-Hugues Anglade), things progress from hot (that opening shot- a long slow dolly-in of them passionately making love- a lush climax of any given trashy romance novel, front-loaded here) to bare (the amusing informality of how these two walk around nude when it’s just the two of them is, for its candor, among the film’s positives) to unhinged (Wait, this girl is violently nuts!!) to hopeless.

When Betty can no longer be that sexual lynx in the eyes of Zorg, what’s a girl to do but wildly razor-cut her hair into abrupt tufts and grotesquely smear clownish makeup on her face? (The answer: punch through a window or two, shout a lot, and land oneself in a French small-town sanitarium. Catatonic and unable to conceive is no way for a once-vibrant girl to live. So deduces the bereft Zorg, at any rate.

Perhaps that previous paragraph can be read as containing spoilers, but really, how can that possibly matter? Betty Blue is the very definition of a film where this happens and then that happens and for while they do this and then they go off and do that and eventually she announces she’s pregnant, but that’s complicated as well, and then they get one of life’s left turns that no one, except for most anyone, could see coming. It’s a hollow movie that can’t be bothered to try to transcend its horsecrap premise, or to acknowledge it as such.

Beineix is interested in color and texture and bodies and skin. Which is fine, except, that’s literally it. And the three hours of Betty Blue, trying as they might, cannot sustain any of those four things for more than, you know, ten minutes? (Although, the film wasn’t always this long- this is the extended director’s cut). The tease of more works up to a point (your milage will no doubt vary, but let’s drop a pin at the midway point), but sooner or later, the frustration sinks in that with this movie, you can’t get no satisfaction. Though it tries. And it tries. And it tries. And it tries.

The story of a man and a woman, madly physical, living on love (and in this case, sometimes chili) and little else does indeed go back a ways. One thinks of director Ida Lupino’s oft-overlooked 1949 polio melodrama Never Fear, in which a couple of professional nightclub-dancing lovers see their commitment to their sensuous, sultry floor show suddenly vanquished when she is taken down by the degenerative illness. Again, it’s the woman’s inability to figuratively be either “the mother” or “the whore” that drives her downward mentally. In this case, though, the said inner conflict emerges early as the film’s central conflict can and will see itself resolved.

Roman Polanski, with his 1992 erotic neo-noir Bitter Moon, takes things much, much further as that film very effectively seems to be taking and running with the exact skeletal structure of Betty Blue, infusing it with what’s missing: intrigue. Raw, perverse, intrigue. Both films’ central male characters are struggling writers whose talents their lovers believe in wholeheartedly when no one else will. (And, both actors who play these writers [Peter Coyote; Anglade] are top billed over their female leads [Emmanuelle Seigner; Dalle] who are doing the bulk of the heavy lifting- not just backwards and in high heels but also while naked).

The relationship arcs play out exactly the same, though crucially, Polanski (in theory) understands that what Betty Blue lacks is a self-awareness of itself as polished trash. So, that’s exactly what Bitter Moon is. And dare one say, for whatever it may be worth, it’s by far the better for it. It’s got a framework of the angry impotent villain and his femme fatale luring an utterly normie husband and wife (Hugh Grant and Kristen Scott Thomas) into their moral decay, just ‘cause.

This is Polanski having his Betty Blue cake and eating it too. He asks, “What if Zorg weren’t passive but abusive? What if Betty took revenge on him and landed him in a wheelchair? (Not unlike the heroine of Never Fear). What if the rotten assumptions at the heart of the mother/whore dichotomy really got the best of everyone involved?” Now you’ve got a movie. Maybe not a classic, or even a crowd-pleaser. But at the very least, a movie. In the case of Bitter Moon, it is more than the sum of its glossy and firm parts. Betty Blue, on the other hand, is all body parts, firm and nubile to be sure, and with some other gloss. And that is all.

Released to Blu-ray by Criterion at the end of 2019, Betty Blue falls far short of the expectations of quality cinema that the company has carefully cultivated. It is, in fact, one of the slightest entities to ever brandish a spine number and “wacky C” logo. They attempt to make up for it with a submenu full of bonus material:

• A high-definition digital restoration approved by director Jean-Jacques Beineix. This is a major selling point, as the rich and bold pastel-hued cinematography is central to Betty Blue’s seductive aesthetic.

• Blue Notes and Bungalows, an hour-long 2013 documentary directed by David Gregory for Severin and Second Sight. It’s interesting to see Criterion utilizing material created by another boutique label that operates in its shadow. It’s a terrific and unifying move, as there’s plenty of room at the Blu-ray table for both Criterion and Severin (as director Sean Baker will be the first to tell us), and Second Sight, for that matter. Gregory’s doc itself gets at everything most anyone might be wondering about in regard to the film. Who fell in love with actress Béatrice Dalle while filming? Why this longer cut of the movie after the fact?

• Making of Betty Blue, a short video from back in the day featuring a much younger Beineix being interviewed in the interest of promoting the film.

• Le chien de Monsieur Michel, a short film by Beineix from 1977. This sixteen-minute film may lack the polish and scope of Betty Blue, but it surpasses it in being a pure sympathy-generating endeavor. In it, a poor lonely man who’s been reduced for begging for butcher scraps for a pet dog that doesn’t exist finds that cultivating his sham is more work than expected. The effective blend of absurdity and desperation here reveals a mark that Beineix ultimately misses with Betty Blue.

• A seven-minute French television interview from 1986 with Beineix and Dalle.

• Dalle’s original video screen test; wherein we’re taken to the exact moment that Beineix discovers his leading lady.

The printed insert essay, a contextualizing defense of the film by Chelsea Phillips-Carr, is so well written it’s almost convincing. But that backhanded compliment is not meant to refute her words by any stretch. While any good student of high school Speech and Debate is able to take an assigned topic and spin it accordingly, Phillips-Carr does the best job possible in coloring Betty Blue as something other than the gloried blue movie that it is.

The essay gets into the fact that Beineix, a successful director of exorbitant MTV-influenced television commercials, approached Betty Blue as if he were photographing products for sale. In the receding tide of the intensely political and “real” realities of the Nouvelle Vague, this methodology was probably conceived and received as something more legitimately fresh than it should’ve been. Phillips-Carr tells of a whole French mini-movement built around the elevation of surface aesthetic (owing to book covers, advertising, comic strips), also applicable to filmmakers Leos Carax and Luc Besson, dubbed “cinema du look”.

There’s something to this, as Beineix, with this film, is quite likely as influenced by the libidinous and zany animated work of Frank Tashlin. The girl defies gravity, and there’s no shortage of kooky side moments and gags. (Trying to work a piano crane, the pulling of the wrong levers results in multicolored liquids being comedically sprayed in Zorg’s face as though he were one of the Three Stooges).

If Betty Blue truly warrants inclusion in Criterion’s stated mission of “publishing important classic and contemporary films from around the world,” then its prominent placement within this subsection is why.

Otherwise, Betty Blue is like the work of Michael Bay in sheep’s clothing. It’s a sexy sheep, sure, but... that’s just it. Although widely thought of as right at home in an arthouse (Sex and subtitles and auteur audacity, oh my!), the movie is in many ways as commercial as such things come. (Think the film version of Fifty Shades of Grey).

Betty Blue is adapted from the hit novel 37°2 le matin by Philippe Djian and directed as though it were a commercial, for crying out loud. Indulging one’s Madonna/whore complex may not allow for any middle ground, but Betty Blue is otherwise as pitched down the middle as a sexy French drama can be.