70s Rewind: THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION, Reviving Sherlock Holmes

Stories told to us in childhood can shape our entire lives.

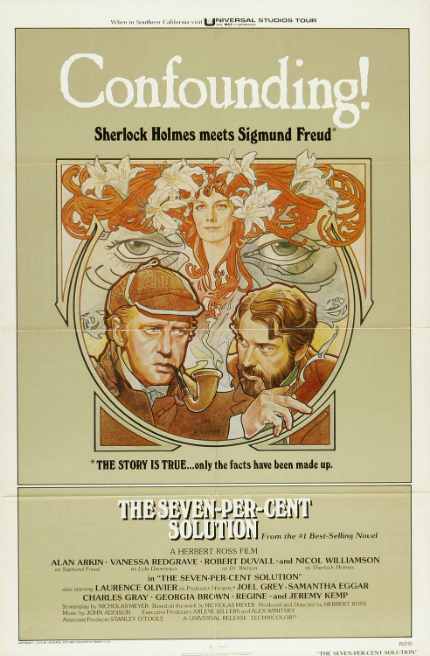

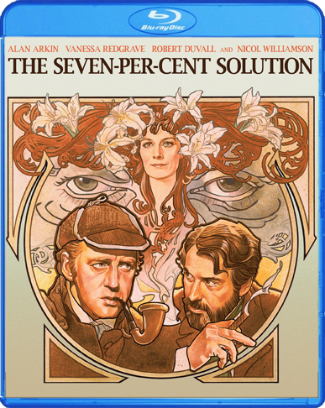

Nicholas Meyer credits his father for the book that defined his career. In an interview that is included on Shout Factory's marvelous Blu-ray edition of The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (first released in January 2013 and available here as of this writing), Meyer recounts a story from his own childhood that inspired him, first to investigate Sherlock Holmes further and, years later, to write a book about Arthur Conan Doyle's famous detective.

Happily, the pastiche novel, first published in 1974, as well as Herbert Ross' big-screen adaptation, first released in 1976, both stand the test of time as delightful interpretations of well-known characters. Even better for those who have read Meyer's novel, Meyer decided to change the mystery that forms the backdrop for the second half of the tale.

Meyer had to fight Ross to make that change because Ross wanted the screenplay to remain staunchly faithful to the novel -- which, of course, Meyer himself had written! Thankfully, the writer won the battle and the film is all the richer for that creative decision (and others).

Ross' push for novelistic faithfulness may be better understood in the context of his career. Beginning as a dancer, Ross established himself as a choreographer and director on the stage in the 1960s. He transitioned to film, making his directorial debut on the musical drama/remake Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969), starring Peter O'Toole and Petula Clark; followed by the stage adaptation The Owl and the Pussycat (1970), starring Barbra Streisand and George Segal -- which I found very very strange as a young man -- scripted by Buck Henry; and the drama T. R. Baskin (1971), scripted by Peter Hyams.

Ross then directed another stage adaptation, the fitfully funny Play It Again, Sam (1972), written by and starring Woody Allen; the clever mystery The Last of Sheila (1973), written by Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins; Funny Lady (1975), a sequel to the popular musical, starring Barbra Streisand; and The Sunshine Boys (1975), an adaptation of Neil Simon's play, written by Simon and starring Walter Matthau and George Burns.

In retrospect, what strikes me about those films is that they all are drawn from stories told by writers with strong, distinctive voices. This is true about The Seven-Per-Cent Solution too: Meyers' voice shines through on the page and the screen.

After graduating from college, Meyers says he wrote a couple of scripts for television, including the memorable The Night That Panicked America (about Orson Welles and War of the Worlds) before he was sidelined by a screenwriters' strike. His companion at the time suggested he finally write a story about Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud, which he had talked about for years. Meyer was surprised when his book sold, and even more surprised when it became a bestseller. Aiming to become a filmmaker himself, he agreed to sell the film rights only if he could write the screenplay. That, in turn, led to his career turning a new corner.

In the early 70s, I fell in love with genre stories; science fiction, especially, caught my young literary fancy. Though I read, and liked, mystery stories, they never caught fire in my imagination -- probably because I lacked the ingenuity to dream up my own mysteries -- and thus I never felt compelled to read the classics of that particular genre. So Sherlock Holmes passed me by entirely; I don't recall reading any of Arthur Conan Doyle's stories or novels.

All I can remember seeing on television is one of the Hollywood adaptations from the late 30s and 40s -- 14 titles in all -- starring Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and Nigel Bruce as his companion, a rather buffoonish Doctor John Watson. Screen adaptations continued popping up in various films and television shows, not to mention in other media as well, but as far as Hollywood was concerned, Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970) may have prompted extreme caution.

Cameron Crowe's book Conversations With Wilder (first published in 1999) includes various mentions about the film and makes it sound like a doomed project. Wilder says he really liked what had been shot, feeling it was the most elegant film he'd ever shot, but thought it was too long. He had final cut; since he had to travel to Europe to start pre-production on another film, he asked a film editor he trusted to do a cut. Without his knowledge, the producers got involved.

When he saw it, Wilder thought it was a "disaster," leaving out entire episodes that he wanted to be included. Later the negative somehow ended up "missing" and he walked away from the project.

The picture, as it exists today, is a fascinating mixture of good and odd elements. It's not any sort of traditional, straightforward mystery, nor it is easy to identify as a Billy Wilder picture. And though it stars Robert Stevens as a distinguished Sherlock Holmes, Colin Blakely plays Dr. Watson as though it were a character in a Billy Wilder comedy, which, of course, he kinda is ... it's a very confusing film, and didn't get much of a release in 1970.

Indeed, Sherlock Holmes' popularity in general may even have waned a bit during the early 70s, which may have been a contributing factor to the instant popularity of Meyer's novel. Reading it for the first time recently, I found it to be a fresh and modern take on venerable characters.

Holmes' addiction to cocaine, which is mentioned in the original Doyle stories, is the initial hook (and explains the title), and its severity leads his friend John Watson to maneuver the detective to Vienna, Austria, so he can be treated by Sigmund Freud. In time, another mystery manifests in Austria, which prompts further adventures.

Eminently compelling and already screen-friendly, it's entirely understandable that director Ross would want Meyer to simply recreate the story entirely for the screen. In the month or so since I read the novel, I've been reading some of Doyle's original stories, which are captivating on their own merits, and am even more impressed by Meyer's skill in suggesting Doyle's original, somewhat archaic, prose style and structure, while adding his own literary inclinations.

As Meyer explains in the 2012 interview, he did not intend either his novel or the film to be 'a Sherlock Holmes mystery.' Rather, he was more fascinated by telling a story "about Sherlock Holmes." In other words: What makes Sherlock tick? And how do you revive a famed detective from a life-threatening addiction?

My awareness about cocaine was completely non-existent in the early 70s, even as a Los Angeles resident, though the drug's use was already climbing in the U.S. This too may have contributed to the book's popularity -- ooh, cute idea, Sherlock Holmes on coke? -- even though it emphasizes the very detrimental effects of addiction.

In any event, the film's initial narrative weight is carried extremely well by Robert Duvall in a very modest performance as Dr. John Watson. He embodies the character as portrayed in the original stories: a loyal military veteran and respected medical doctor who is fascinated by Holmes' skills as a detective. If anything, he is a bit stilted and, definitely, in no way buffoonish.

In any event, the film's initial narrative weight is carried extremely well by Robert Duvall in a very modest performance as Dr. John Watson. He embodies the character as portrayed in the original stories: a loyal military veteran and respected medical doctor who is fascinated by Holmes' skills as a detective. If anything, he is a bit stilted and, definitely, in no way buffoonish.

Alan Arkin can rightly be described as the star; both the character and his performance as Freud steal the show with their straightforward sincerity and strength. (Duvall's Watson is quite rightly defined by his extreme modesty, which feels accurate to Doyle's stories.) Nicol Williamson's always entertaining, stage-honed instincts toward large performances (see The Wilby Conspiracy, for example) serve his character well here. Laurence Olivier (as Moriarty), Vanessa Redgrave, Samantha Eggar and Joel Grey round out the principal cast nicely.

In 1977, Eric Clapton's version of J.J. Cale's song "Cocaine" (first recorded in 1976) became a hit, and a year later, I distinctly recall a friend of mine arriving for a night out already high from the drug.

Meanwhile, Nicholas Meyer next made the fabulous Time After Time (1979), which remains strong in my memory (but deserves a revisit). Herbert Ross next directed The Turning Point (1977) and The Goodbye Girl (1977) before closing out the decade with California Suite (1978).

Arkin would next be seen on TV and then starred in and directed the comedy Fire Sale (1977). Not too long after that, he starred in The In Laws (1979), which sits on my shelf from Criterion, calling out for a revisit almost every day. Duvall appeared in a little movie titled Network (1976), released just about two months later, while Williamson made a great guest appearance on Columbo and then moved on to Neil Simon's The Cheap Detective, while Vanessa Redgrave would next win an Academy Award for her performance as the titular character in Fred Zinnemann's Julia, a Blu-ray that is also sitting on my shelf, waiting for a rewatch.

In the 21st century, Sherlock Holmes adaptations have flooded screens, so it's difficult not a version of the consulting detective somewhere. Still, I'm glad I finally watched the very entertaining The Seven-Per-Cent Solution on Blu-ray and look forward to watching it again. In the meantime, I've invested in my own collection of Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories and am enjoying them immensely.

As for myself, I never tried cocaine.

70s Rewind allows the writer to safely indulge in his love for all things 70s, especially movies.