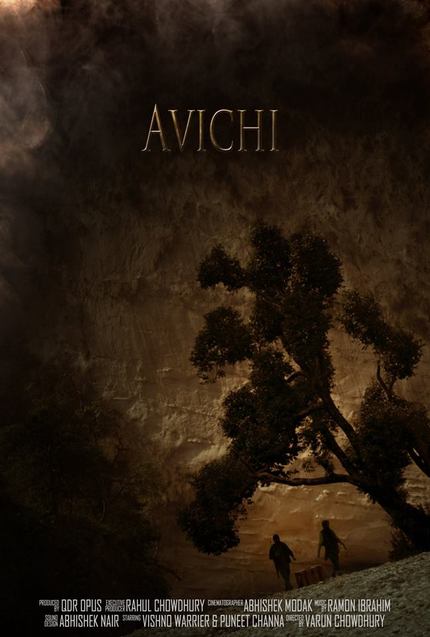

Kolkata IFF 2017 Review: AVICHI Rewrites The Rulebook For Indian Cinema

Puneet Channa and Vishnu Warrier Star in Varun Chowdhury's Silent Apocalypse, AVICHI

Have you ever wondered what a cross between The Road Warrior and The Seventh Seal might look like? Well, with Varun Chowdhury's debut feature Avichi you get a glimpse into that world, and it is an exciting vision. A film that challenges all that is expected of Indian cinema - melodrama, light and color, music and dance, physics defying action - Avichi expands the palatte for subcontinental films to include meditative apocalyptic drama of which everyone involved has a right to be very, very proud.

Avichi is a sanskrit word that describes the concept of soullessness. In Buddhism it describes the lowest level of Hell in which those who have committed the gravest of sins may attempt to be reborn. Chowdhury's Avichi is a barren landscape over which two nameless men tread with no ambition but to survive and perhaps to atone for the sins and losses of their previous lives. When two men bond over the mistakes and losses of their previous lives, but the chance for redemption is only offered to one, how will they react? It's a fascinating exploration of fragility, masculinity, and the depth of empathy that is unlike anything I've seen in years.

One of the huge stumbling blocks for Indian regional cinema is a language barrier that none but the most dogged of cinephiles are willing to climb. Avichi circumvents this challenge by removing language from the equation almost entirely, save for a few on screen texts in English. A dialogue-free experience made me incredibly wary, but the performances from lead actors Puneet Channa and Vishnu Warrier were pitch perfect in expressing the kind of deep pathos required to engage an emotional connection with a story that is intentionally open to interpretation.

The lack of dialogue is both a blessing and a curse. Speech and dialogue are our connection to the characters in any film, even if the language is not one that we speak, we are able to understand story and motivations largely due to the kind of exposition that spoken language provides, and art-house films like this are no exception to that rule. However, in India, a country with hundreds of native languages and dozens of language based film industries, this can put up barriers. Avichi's commitment to telling a universal story without any spoken dialogue at all is not only incredibly risky, but also potentially very alienating, though the team accomplishes their goals masterfully.

While it may sound like a challenging watch - and that's not entirely untrue - the film is truly engaging because of the work of a team beyond just the on screen leads. Right from the start of the film it is apparent that we are in safe hands. The cinematography by Abhishek Modak is exceptional, his use of framing and light is key to delivering the perfect backdrop on which Chowdhury's story can take place. There are amazing vistas in Avichi that highlight and enhance the experience for the viewer and give the performances of Channa and Warrier the kind of setting required to express their increasingly tortured existence.

Modak's cinematography is exceptional, but he's far from the only artisan on the project who deserves notice. Without dialogue, all of the creatives on the set needed to work together to provide the kind of palette that would express Avichi's story and vision, another such talent is the composer, Ramon Ibrahim. Ibrahim provides a mix of Indian raga and a sort of Appalachian noir feeling through his music that is incredibly effective in driving the emotional journey of these characters. Pensive and weepy strings punctuate the film and help us to feel what these two travelers experience in a way that is nothing less than perfect.

Avichi is not a perfect film. It's a little rough around the edges, for sure. It's a bit to clean visually when it should probably feel a bit more lived in, but it is absolutely beautiful and poignant, and - most impressively - unafraid to be what it is. At a touch over ninety minutes, the film doesn't overstay its welcome, but also understands that its audience will be selective. After all, this is essentially a silent film, a market which isn't exactly burning up the box office.

What writer/director/editor Chowdhury has accomplished with Avichi cannot be understated in an increasingly competitive environment for Indian independents which finds them fighting for screen space all across the country. Not only does this film challenge the expectations of its homeland, it does so in such a way that I'm impressed that it got made at all. As much as it dismays me to say this, I have grave doubts about Avichi's commercial future, but none about the future of its creators. From the amazing cinematography, to the incredible score, to the powerful acting performances, right on down the line to its impressive art direction, Avichi will be a powerful calling card for all of its creative talent.