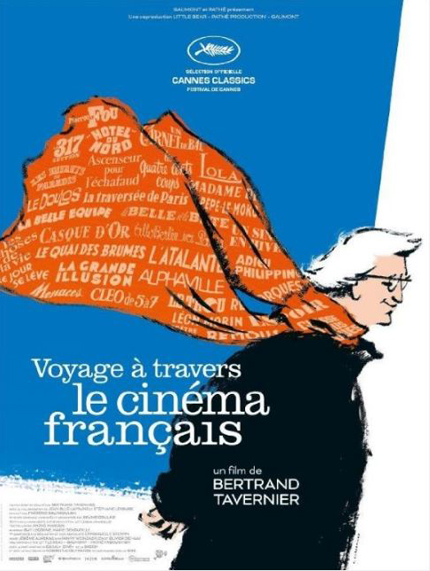

Review: Bertrand Tavernier's MY JOURNEY THROUGH FRENCH CINEMA Proves to Be an Invaluable Resource Guide

French filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier takes a deeply personal dive into the impact of French cinema on him and his films.

In A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (1995), the famed director announces in the beginning of the film that he can't be objective about what films he would mention in the historical documentary. Justifying his personal take on the endeavor, he said. "It's an imaginary museum and I can't open all the doors. We don't have time for all of it."

In My Journey Through French Cinema, veteran French filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier takes the same route; the doc is not a French cinema history, from Lumiere to Luc Besson, but rather a deeply personal take on the impact French cinema has had on his upbringing and later as a filmmaker. So it starts with Jacques Becker (Dernier atout, Casque d'or) and ends with Claude Sautet (Les choses la vie, Un coeur en hiver).

Clocking in at 3 hours and 20 minutes, My Journey is definitely not a clean cut doc that has a definite ending. In order to make sense of the chronology and to give context to Tavernier's narration, it is necessary to go through the director's own background a little: Tavernier (The Clockmaker, Coup de torchon, Life is Nothing But), born in 1941 to working class parents in Lyon, is a member of the liberation generation. He associates the liberation after the end of WWII, celebrated in the sky above Lyon, with the magic of the theater-going experience.

Having suffered malnutrition during WWII, he was a sickly kid who spent most of his childhood watching films. His isolation made him a cinephile well versed in American films as well as French. His first movie job was working for Jean-Pierre Melville as an assistant. Then he landed a job as a publicist for a studio (which produced Breathless), then as a film critic. He worked for Claude Sautet before making his debut as a filmmaker with The Clockmaker in 1974.

A bit younger than Godard, Truffaut and the rest of the French New Wave directors who rejected old ways of filmmaking (for the sake of the explanation, I'm grossly generalizing here), Tavernier is an ideal candidate to chronicle French cinema somewhat objectively. He is a filmmaker with an old-school sensibility but also had intimate working relationships with the French New Wave directors.

All throughout, he points out the differences among French films and that of Hollywood films. He grew up seeing the films (made in 1940s-50s) of Jacques Becker, Jean Renoir (La bête humane, Grand Illusions), Marcel Carné (Children of Paradise, Remorques), Julien Duvivier (Pépe le Moko, Panic) and Jean Vigo (L'atalanté, Zero conduit) among others.

These directors, although influenced by Hollywood directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks and Ernst Lubitsch, had an innate distrust in plots and put more emphasis on empathy and emotions. Thanks largely to gifted writers like Jacques Prévert, unlike plot driven American movies, we unhurriedly follow characters and invest in them, as they discover their destination as we the audience do at the same time, like in Carné's beautiful, lyrical Port of Shadows.

Since it's a personal film, Tavernier keeps talking head interviews to a minimum, unless it's old interview footage or a recording from years ago. He puts emphasis in the differences of French cinema from its American counterpart. He also concentrates on three categories: directors he admired growing up, music composers, and directors he worked for in one capacity or another.

Using the legendary actor Jean Gabin, who starred in many classic French films, as a springboard and transition device, Tavernier jumps through many directors who worked with him and shares many anecdotes. According to Prévert, Marcel Carné was not an actor's director. He notes that Carné was the only director who wasn't capable of writing a scene. But he was master of shot/reverse shot and preferred using a wide lens instead of different combination of lenses.

Film scoring is a big interest for Tavernier. Unlike prevailing scores from beginning to end in a Hollywood production in the studio days where directors had no say on music, French directors carefully chose their scores and music composers. They were discreet about when to use music. You can’t help noticing the memorable melodies after watching Vigo's L'atalanté by Maurice Jaubert, who also scored music for Carné for Port of Shadows and Le jour se leve, and Duvivier's Un carnet de bal, among others.

Tavernier is an unabashedly old-fashioned filmmaker. He firmly believes that filmmakers have to possess both arrogance and humbleness -- you make films thinking that you can change the world, but you must be humble enough to realize that if you can touch two people with your films, your job is done.

Tavernier talks fondly of Truffaut. His direct comparison of Truffaut with Jean-Pierre Melville is very revealing. Truffaut was gentle and calm and his nature was reflected in his films. Melville, however, was a brute to work for. But he had a sense of humor. The only reason Tavernier got hired as an assistant was Melville read a scathing review of Bob le flambeur by Tavernier. He thought Melville's craft amateurish. To young Tavernier, his films are either utter crap or masterpiece. He saw the director of Le samurai and Léon Morin, prêtre up close and personal and decided that he wasn't a good original writer but a fabulous adaptor. His usual cinematic elements -- bars, dancers and mirrors -- were from his real life.

Shooting everything in his studio, using the same stairs and entryway multiple times throughout different films, Melville was a crafty, economical director. With no music, out of frame action and long sequences, even though he was influenced by Hollywood gangster films, Tavernier concludes that he was closer to Bresson than Wyler.

It was in response to Melville's suggestion that Tavernier became a film publicist. "You are a terrible assistant, but you'd be good at defending films. Why don't you become a press agent?" He got a job at Rome-Paris Films, a small company that was basking in the surprising success of Godard's Breathless. There he met and interacted with Godard, Truffaut, Agnes Varda, Jacques Demy and Claude Rosier.

Although he was not a part of it, he understood what the New Wavers like Godard and Truffaut were trying to do. He remembers Henri Langlois and his influence on a generation of filmmakers. For a young cinephile, Langlois's eccentric programming was an eye opener. Tavernier was there, along with his classmate Volker Schlendorff in 1968, outside Cinémathèque Française when the police clubbed the young crowds demonstrating the closing of Cinemathèque.

He introduces Godard's Alphaville by way of Eddie Constantine, an actor who starred in many b-movie spy thrillers (by Hollywood blacklist director John Berry), playing the role of Lemmy Caution, which Godard borrowed. He goes on to speak about Godard's propensity for cinemascope, colors in films like Contempt and Pierre le fou, with much admiration.

He remembers fondly about Claude Sautet, who became Tavernier's mentor. He says Sautet was on the fringe of the French cinema industry and the mean boys at the Cahiers du Cinema didn't give him the time of day, probably because he often depicted bourgeois lifestyle. Not only Sautet directed films but he was a script doctor for many of France's most popular films.

I've seen some of Tavernier's films from his long and illustrious filmography. I was struck by his subtle, humanistic approach when I saw Captain Conan, his WWI film in theaters in 1996. Encountering films like The Clockmaker and Coup de torchon recently for the first time was a pure joy for me. I definitely see the lineage all the way up to Jacques Becker, who presented his working class characters as real as possible -- we see a carpenter really working those carpentry machines, a print setter actually dirtying up his hands, etc. In his films, we see the silly slapstick elements and unrehearsed playfulness of the New Wave. In his films, we see great subtlety in the writing and performances of the late Sautet.

Obviously, My Journey Through French Cinema is a lot to take in one sitting. It's also a goldmine for any cinephiles as an invaluable resource guide. Tavernier is doing us a great service here through his experience as a cinephile and a filmmaker. I am eager to check out more films that are featured in this documentary for years to come.

My Journey Through French Cinema is scheduled to open in New York on Friday, June 23 at the Quad Cinema, followed by a national roll out.

Dustin Chang is a freelance writer. His musings and opinions on everything cinema and beyond can be found at www.dustinchang.com