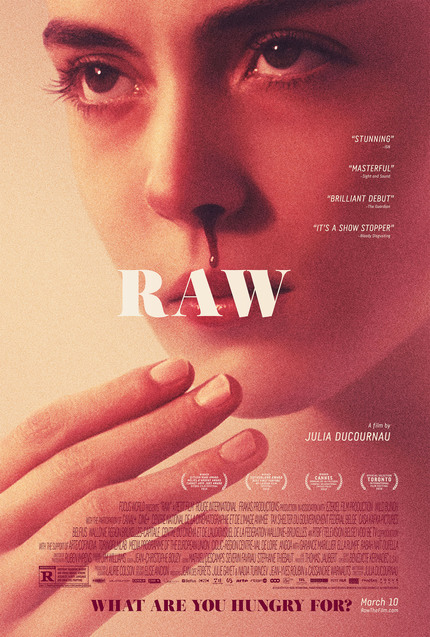

RAW Interview: Julia Ducournau on the Thematic Charge and Cinematic Language of Her Cannibalistic Shocker

2017 is off to one hell of a start for fans of horror. Hot on the heels of box office breakout Get Out American audiences are soon being treated to another high caliber genre effort that does not shy away from social critique. What sets Julia Ducournau’s debut apart from the former, however, is that Raw wraps its thematic audacity in the gooey viscera of cannibalistic carnage that is sure to titillate gore hounds.

The film follows doe-eyed vegetarian Justine to veterinary school where she is reintroduced to her older sister Alexia. Shortly after arriving she is subjected to hazing rituals, one of which forces her to eat a raw rabbit kidney. The all but involuntary consumption awakens her carnal cravings in more ways than one.

I had the pleasure of meeting writer-director Ducournau and actress Garance Marillier, who astounds in the lead role. Both were very generous with their time and spoke passionately of their labor of love. Read on for my talk with Ducournau and be on the lookout for my interview with Garance Marillier, set to be published later today.

[note: minor alterations were made to the transcript below to make the interview as spoiler-free as possible. Even so, be advised that Raw’s themes and character arcs are discussed.]

ScreenAnarchy: Raw is an enormous success. From Cannes 2016 to Sundance 2017 with several high profile genre festivals in the months in between; it’s quite unique for a film to play such a broad range of festivals yet also fitting because Raw contains the ingredients to please all manner of audiences. From body horror to social commentary, dark comedy to drama your film functions on different levels. The music (with its organ elements) even gives Raw a touch of the Gothic. Did this eclectic mixture come together organically while writing the screenplay or did you know beforehand you wanted to tell a story with crossover appeal?

Julia Ducournau: Very organically, actually. I don’t set myself the challenge of ‘ok, I’m gonna mix genres and choose them from all possible genres that exist’. The first time I ever wrote and directed something, when I was in film school in the first year, I had no idea what I was doing, obviously [Laughs]. But it just came together like that that my work was indeed very dramatic, very graphic, with let’s say a reality that was ‘on and off’. These were really short films, three minutes or so. There was no comedy yet. That’s maybe what I hated about them because I really need to be able to relate to a character through humor. I do think that the character [Justine] makes you laugh at the beginning of the movie; that’s to say a character with whom you laugh, and not a character you laugh at. You laugh with her. I think it really creates a bond between you and this character that lasts for the whole movie.

I really believe in the power of comedy, especially when it’s in a context that is very dark. And I do believe that darkness makes laughter way deeper than it can be when it’s alone. It gives some kind of perspective to laughter. For me all these genres just came up, I think, organically out of me, and I always tried to make it a bit more precise, trying to tackle my own language and understand it – how it works, and everything. I really see it as a language, to be honest. I can’t all of a sudden decide to make a musical, for example. I love musicals but I haven’t seen that many and it’s not my language, it’s not something I can incorporate in my vision of the world right now.

Again, I do think that genre doesn’t work without laughter because laughter can really come up as a catharsis in genre films. It can also come up as something that kind of flatters or accentuates the genre, in a sense that it makes you feel at ease when you see a comedy scene and you laugh with a character, and then BAM, with the eruption of genre all of sudden you feel this sensation of ‘wow, what’s going on, what’s happening in this moment’ … It gives une réaction épidermique [a knee-jerk reaction]. Both go very well together, and drama with laughter as well, as explained before.

That’s how those elements came up and now I’m trying more and more to master my language as much as I can.

But I imagine it’s a difficult balancing act. With so many components, how did you ensure one did not overpower the others, and succeed in making a film that’s tonally consistent in a unique and hard to pinpoint manner?

[Laughs] Three years of writing. It’s a lot of precision work. The fact is that the way in which I use temporality in my movie is not classic or Hollywoodian, it’s not very fluid and doesn’t go from one character to another. The way I write is really from scene to scene, in blocks. I tend to compare it to capturing impulses. My movie is very much about impulses and I write in an impulsive way. I tackle the impulse of the scene every time and don’t care what’s in between scenes which gives a kind of rhythm that is superfast. If you take one scene out of this evolution, then basically your card castle falls apart in seconds. So you really have to balance everything and plan … My scripts are super precise, very detailed, and are almost already edited. What you’ve seen in the movie is almost exactly the script.

I was going to ask about that next. I knew I would like your film the moment we are introduced to Justine, when she’s sitting in the back of the car and she pushes the dog away from her, but as soon as those grey and imposing building of the veterinary school are in sight she pulls the dog closer to her. This is a small visual detail that speaks volumes about where the protagonist is at emotionally.

Of course.

So you place a lot of emphasis on the importance of visual language and I was wondering how much of that is already in the screenplay?

Everything [Laughs]. Just like you said, for me movies in general and genre movies in particular are all about images. Images build a language of themselves. For me if you watch the film at home you should be able to turn off the sound and understand what’s going on with the character, not only just in terms of plot, but what’s happening inside each character, what they’re feeling, just by watching your screen. For me, if I manage to do this, that’s everything I could ever want. I don’t like explanatory dialogue at all and that’s why you’re right, it’s a lot of details like this that I always try to include when I film. I’m thinking ‘oh, she feels like this or that. How can I show it?' Not: 'how can I explain it to audiences?’

As a cannibal drama, Raw reminded me of the Spanish film Somos Lo Que Hay …

It’s Mexican, actually. But yes, I saw that one.

As a dark coming-of-age film that combines horror and comedy it shares DNA with John Fawcett’s Ginger Snaps …

Which I still haven’t seen. It’s been a year that people point out parallels … I really have to see it and meet the person who made it, apparently, because we have a lot in common, I am told. [...] I really want to see it badly.

The graphically explicit scenes recalled the body horror of David Cronenberg. Were you directly influenced by any films when writing and planning Raw?

Hmm, the thing is that when I write I try not to watch the movies that have been influencing me in my life in general. I just don’t watch them again in the whole process of the three years of writing Raw. I do not want to be tempted to reproduce anything. I do believe that I, like everyone, belong to a history and in the moviemaking world I belong to a history of cinema. So of course I am not only influenced but a lot of directors and their work have gone through me throughout the years. These movies led me, irreversibly, to what I’m doing now. That’s what I believe in in a way, in terms of influences. I let myself digest them – no pun intended, but now I can apparently only make puns when I talk about my movie [Laughs] which is frustrating. But they go through me and then I just try to make what’s in my head without questioning if it comes from this or that.

When you work with your crew, so when you’re done writing, somehow you have to give them some reference points to help them imagine what you have in your head. For example, with Ruben Impens, my DOP [Cinematographer], I told him lots about Korean movies for the lighting. I’m crazy about Korean DOP’s by the way … It’s always crazy and this kind of really claire-obscure I absolutely love. For Garance, at some point, for two scenes, I showed her Zulawski’s Possession just to show her how an actress can really let go of everything she is in real life, and just fucking let go. How free she is in that scene is amazing. But these movies are not necessarily my influences when making the movie, not consciously at least. […] even if these movies are some of my favorite ones, also including Crash or Suspiria, when I was doing it, I had no idea that it was somehow influenced by them.

The only direct reference that there is in my movie is Carrie for the blood shower. I didn’t include it because Carrie is one of my favorite movies (I like the movie but it’s not in my top-five), but I knew that considering the premise of my story everyone who has seen it will think about it because of the school setting, the blood, the young virgin ... So I decided to have fun with it, to just wink at it and then after it’s over, we can just move on, you know.

When I spoke with Garance she told me that the gore scenes were actually not the most difficult to film. Instead, the basement party, early on in Raw and shot in one take, was more challenging.

Yeah, absolutely, on paper it was the most difficult one and technically it surely was tough because I had a lot of ambition for this scene. There were a lot of people, 300 extras, and the crew on top of everything in a very closed-in space … It was kind of claustrophobic. But let’s say that I had fantasized about this shot for so long. I had prepared myself for so long, choreographed everything in advance because of course you can’t come on set with your camera and start to figure out, ‘ok, where do I put the camera’ … It was really a lot of work but then, to be honest, it was my favorite scene to shoot because it was a real communal effort, directing everyone, and I love the fact that everyone wanted this scene to look good once they understood what I was going for, and after I explained to them why, usually in movies, I don’t like party scenes because it takes my away from the scene … I always notice that one extra who is pretending to dance and stuff like that …

While there’s no music actually playing …

Yeah, exactly! I hate that. I tried to do something really different, which is why actually there was music on set for, like, the whole day. Super loud, and we would only turn it off for the dialogue. It was really a group effort because everyone understood and wanted a new kind of party scene. When we managed to have two perfect takes, which by the way is more than I expected to have, it was a total blast, everyone yelled and continued dancing. It was amazing. That scene was the most difficult, technically, but also the best one I shot.

You end that scene, very interestingly, with a close-up shot of a stuffed animal hanged by its neck, to signal the start of a loss of innocence for Justine.

[Laughs] Of course.

The stuffed animal is a plush sheep, a herbivore, and the transformation Raw follows is that of a vegetarian who will become not just a carnivore, but even a cannibal.

You went far on this one. The sheep, to be honest, was chosen because of the saying ‘to follow someone like a sheep or behave like a sheep’ [‘se comporter comme des moutons de Panurge’] and this is what hazing is about, docile sheep.

Conformism due to peer pressure.

Exactly. That’s why I chose the sheep, but also because I think they’re cute.

Justine is a very nuanced character. A protagonist who is neither black nor white, and particularly a woman who is neither beauty nor the beast, who has both tragic and monstrous qualities. How important was it to create such nuance?

Oh man, that by the way was really hard to achieve when writing her. It took me a very long time to be able to stand by my character because for a long time I was aiming for this nuance but didn’t find it. People liked Justine anyway because she was funny and everything, but I did not … I could not see her depth for a long time. I mean I got my story, my structure, my secondary characters and everything but her I always had a problem with. Very far on, in the fifth draft out of seven, I understood something; this is where it clicked. When I got it is when I saw her flaws of character. This is when I could identify with her as a human character because before I could not understand this kind of ‘white sheep’ … Is that an expression?

You mean this totally pure, innocent figure.

Yeah, exactly. I couldn’t identify with this woman at all. When I realized she could also be a shitty sister, like when she’s correcting her sister’s papers, when I understood she’s also a bit self-involved, and self-centered, then I started to have a grasp on her. I understood the importance of what was gonna happen to her, how important it was that she discover her humanity by undergoing this birth of monstrosity. Because at the beginning she thinks she’s so perfect, you know. Of course she feels vulnerable and everything in this context but she’s a good student, she’s the A-grade student. She comes and has finished her test before everyone else, and she’s happy about it, and then she’s gonna become the most flawed person in the world with what happens to her. This is where she can actually grow up for real. This is how I managed to have a grasp on her but she was really not easy to write at all.

Maybe I’m reading into your film but coming from a background in literature, with a naïve, innocent protagonist named Justine, and a story that is about sexual awakening as well it’s easy to think of the world of the Marquis de Sade [“Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue”, 1791].

Of course, that’s exactly why I called her Justine.

But the interesting thing is that your Justine is never just a passive victim of circumstance or an object. In her coming of age, to an extent, she starts to imitate the behavior of her sister, Alexia, who reminded me of Juliette, the way Angela Carter described her in “The Sadeian Woman” (1978). So I was wondering, was Angela Carter’s world and her feminist writing an influence on your film as well, direct or indirect?

I am familiar with it, however, I never thought about her work while writing my film. I did think about the Marquis de Sade, that’s obvious, but I want to comment on two things. Justine discovers pleasure through what she experiences. Of course she’s an object but for me she gains power when she manages to have a grasp on what’s happening with her by feeling pleasure in it. She’s not that passive and that’s actually why I called her Justine because of this progression towards orgasm, towards pleasure. The second thing is that Justine doesn’t try to imitate her sister. The only moment in which she wants to become her sister is before this starts happening because her sister is so confident and everything and Justine wants to get in the frame, she wants to be like everyone else. However, her sister is completely integrated in the group, which Justine is clearly not.

Justine has admiration for her sister, she craved meeting her again and missed her, but the only moment you can tell she really wants to be like her is during [a certain dorm room scene] [edited to avoid spoilers]. There is a tribe that I read about in Claude Levi Strauss’ “Tristes Tropiques” (1955), Claude Levi Strauss being a big anthropologist who worked a lot on cannibalism … A very famous and smart guy. He wrote about this tribe in Brazil that practiced the rite of eating a piece of their enemies’ body when they’re dead in order to both annihilate them and to digest their forces; to make them theirs.

To incorporate part of them.

Absolutely, and that’s what’s happening in this scene. It’s not by chance that Justine is in the room with her sister because I could have chosen anyone else, but it’s because she wants her strength. She wants to be her at this moment. So, this scene has several other meanings, such as a rebellion against the establishment which her sister embodies through the hazing rituals and everything, there is that too, but this tribal thing is really at the center of my film. Afterwards, when Justine starts to spot the perverse effects of her nature being revealed in her she starts to make her own way. Her sister has actually become her nemesis. […] she realizes her sister is an animal, she only abides by her primary instincts [… edited for spoilers]. Justine doesn’t want to be an animal. For me their trajectory is an X. You have an ascending trajectory of Justine towards humanity, towards the consciousness of right and wrong, and you have the descending trajectory of the sister towards animalism.

Both of which converge at a single point, before diverging again.

Absolutely.

Your film is a critique on the dangers of conformism but also sexist socialization.

Definitely, yes, a critique is the least you can say. It’s not just the way I see how the world is today and how I tried, from a feminist angle, to propose other possible options. My film is feminist in how I treat the female body in it. Of course, as I told you, I’m obsessed with bodies but not all bodies are the same and not all bodies are to be treated the same way. Here with this young woman who discovers sexuality I thought I had a lot to defend because, usually, young women’s sexuality is portrayed as something that is very cerebral, that is very much in the head, projected on what’s ‘after’: 'Is he gonna call me? Is he the right guy? Am I gonna pass for a slut? Will I get a reputation?' That’s the thing they propose to you, people who are in doubt, constantly in doubt.

But doubt is not sex, it’s not sexuality. The head is not sexuality. The body is sexuality, is animalistic, desire, and I wanted to put this young woman’s sexuality back in her body. I wanted it to be shameless and unapologetic, and aiming at orgasm like any other body when it comes to sexuality. That was incredibly important to me. The second thing with this body is that I tried to show it in its very ‘raw’ triviality. The fact that it’s trivial is very important to me, that Justine sweats, that she pukes, that she pees, that she has dark rings under her eyes, and is ugly sometimes and endearing at other times. I always find trivial things to be very endearing. I mean, as I told you, the flaws are how I can have a grasp on the people I write. I really like that, and it works for the bodies as well.

The fact that we see her like that and that she’s not sexualized and is not glamorized helps me take her out of her niche, like for instance Disney’s niche of glamorization or sexualization, to show her instead as a universal body. Everyone has hair, sweats, everyone farts … All of a sudden it’s not just a woman’s story. It’s an everyone’s story because the question that is at the center of my movie is: What is it to be human? And this does not only concern women.

And that’s how you transcend gender roles of ‘the’ masculine and ‘the’ feminine, whatever those are, and whatever the societal conceptions of those roles may be. You take it back to that primal urge.

Correct. For me, there is a promise of equality in there, that’s for sure.

This is a very exciting time for genre films. In the past few years we have seen many new voices, many female voices as well, creating intriguing works or modern classics. From Sarah Adina Smith and Ana Lily Amirpour, to Karyn Kusama and Jennifer Kent who used the boogeyman as a metaphor for grappling with trauma in The Babadook. You use the genre element of cannibalism to address the horrors of real life. How do you see yourself in this tradition?

Well, I agree with you about these amazing female voices that you cited. I’m very much a fan of like 90% of them; the other 10% I simply haven’t seen, yet [Laughs]. But I must say that in this wave that you’re describing I would also include men. Movies like The Witch or It Follows are exactly in the same vein. The thing is that, people very often ask me about other women directors in genre film and I do understand this question because it is almost historical that in such a short amount of time so many female voices in genre have managed to express themselves; that people who have the money gave it to women so they could express themselves in film. I can only hope it’s a very good sign for the future and I can only pray that this is not considered to be a trend. That would be the most terrifying thing I could imagine, that half of the planet is a trend. But I would include men in this recent tradition. Definitely The Witch is in this vein and It Follows as well.

Both films center around interesting female characters and offer layered takes on sexuality.

Absolutely, I totally agree with you. And they talk about it perfectly. I mean, this is the thing when you write something. You can write any character, a man or a woman, a giant rat, a baby, an old man, whatever, you name it. It’s your job, you have to have imagination and to put yourself in the field. It has nothing to do with the gender of the people who are making it. I can relate to men, no problem, so why can’t men relate to women?

I have a feeling we could easily spend another 30 minutes discussing your work, but you have already been very generous with your time, so I will simply ask a final question. In a 2016 interview with IndieWire you mentioned you were writing your second feature film. What can you tell us about this project? How far along is it?

[Laughs] Unfortunately I can’t tell you more than what I told IndieWire for many reasons, the main one being that I have a pact with my producer not to say too much about it just yet. Secondly, with the crazy year we’ve just been through, honestly, it’s been very very hard to write. So in April I’m just gonna lock myself inside a closet and just write for eight months and don’t talk to me. That’s what it’s gotta be. But all I can tell you is that in terms of language – people often ask me this question, ‘are you still gonna be in the genre realm?’ – of course, what I’ve done with Raw, this crossover of genres that I explained to you and that is so dear to me and I’m trying to master, I’m gonna keep on working on that because I’ve only made one feature. It’s not like I did ten, and I’m tired of it.

I really enjoyed this conversation with you.

Me too, thank you very much.

Raw, a tasty treat for fans of intelligent and visceral genre cinema, hits select American theaters on March 10.