Review: DARK NIGHT, A Meaningful Document of America at Seismic Crossroads

Tim Sutton's third feature film is an elegiac work of expertly expressed cinematic artistry.

Close your eyes. Picture the various scenes:

You gotta keep your head down. She runs her hands through your hair; it's so short it must feel like walking barefoot on freshly cut grass. The burnt orange dye bleeds into your scalp. You gotta keep your head down. It feels good. She says it's supposed to feel like you're dying. She says this as she lunges, weights in hand, sweat gleaming off her skin, badges of honor for the pain she's in. She says this. She feels this. She screams. You don't get to hold your son everyday. You're holding your son. You're cleaning your guns. It feels like you clean your guns everyday. She is lying on the beach, sun glistening off her skin. You walk over the front lawns, holding your rifle like a pro. Why do you feel this way? You are holding a turtle like a hamburger. You are trying to find the life in its eyes. Where is it? She blinks. Lights flash across her face. At first we think its the light from a projector, flickering dozens of images, sacred in their chaos, across a movie theater screen. Maybe its fireworks. Maybe it's not. They are emergency lights. A benevolent red/blue. She blinks. She sits on the curb. Where is her breath?

Breathe into the tension. And let go. But don't disconnect.

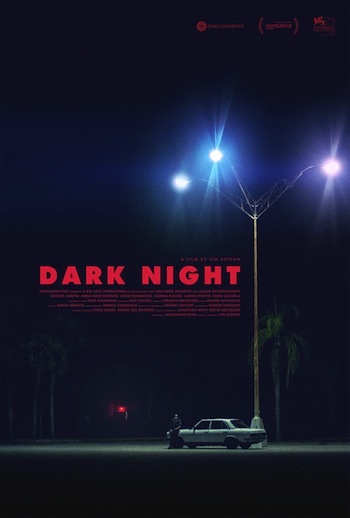

Filmmaker Tim Sutton returned to Sundance's NEXT program in 2016 with his third feature film Dark Night, an elegiac work of expertly expressed cinematic artistry that looks at America as it is today, in the midst of a rising tide of isolationism and acute loneliness. Dark Night, despite being inspired by the cineplex shooting in Aurora, Colorado, is not a gun control movie.

If it has a social agenda it is one that rides on sheer emotion and sympathy first, charting a geography of apathy across the secret blight of suburban America, landing on the stained Sarasota, Florida as the umpteenth ground zero. Sutton's focus is not on the shooting though. The film works as a collage of different and intersecting lives, some named, others nameless, most young, all moving towards the event we get a glimpse of in the film's opening.

We first visit Aaron (Aaron Purvis), the young social outcast and the subject of a documentary film crew,. Home schooled since his brutal middle school days, he is a dark philosopher who has seemingly already cracked all of society's putrid, brittle innards, finding the gnarled truths kept therein.

Then there is the latina teen (Rosie Rodriguez) who works at the big box store on the weekends. She eyes the pretty white girls. She's happy. She's been hanging out with them more. They even invited her to the beach. The war veteran (Eddie Cacciola) can't keep it together enough to see his son. He goes to group meetings. Other men laugh. Other men cry. He goes to the gun range.

Meanwhile, the boys just want to skateboard and vape. The girls want to go swimming.

A young woman named Summer (Anna Rose Hopkins) perfects her body till it hurts. She poses for selfies, she updates her Youtube, she goes on auditions for local modeling and acting jobs. Robert Jumper (played by Robert Jumper) goes home to his mother. He has milk and cookies. His father is out of the country. She gives him money. Robert Jumper counts the steps from his white Mercedes to the cineplex.

Sutton's lyrical docu-drama aesthetic frames this swatch of melting-pot stories (populated by nearly all non-professional actors) to gloriously tender effect. Dark Night is not a film that wants to point fingers. It is a film that wants to cradle, to hold close the fear and apprehension of the American people.

Lit by the dim glow of their computer and phone screens, our on-screen counterparts encourage us by their own apathy to see our own ability to disconnect from the world around us. How can we hold sympathy for others, let alone any empathy, when our perceptions become so fragmented, rising on a culture of branded white noise. Or can it be that the young of today are finding salvation across these new realities? Perhaps a crisis of selfies isn't so much a crisis of faith as much as it is a moment of affirmation.

On one hand, Dark Night does work as an honest depiction of working class and middle class lives, as well as the youth who find themselves as outliers; not homeless, per say, but not of an economic class which fits into data and statistics. These are the wanderers. While this is not a film that wants to live on class commentaries it feels important to note this as I see few American narrative films these days that just simply show our country as it is today; a country of many faces, many hopes, many fears.

On one hand, Dark Night does work as an honest depiction of working class and middle class lives, as well as the youth who find themselves as outliers; not homeless, per say, but not of an economic class which fits into data and statistics. These are the wanderers. While this is not a film that wants to live on class commentaries it feels important to note this as I see few American narrative films these days that just simply show our country as it is today; a country of many faces, many hopes, many fears.

As Sutton's first two features, Pavilion and Memphis, proved to be poems of and for our era, so is Dark Night. In 30 years time, looking back across millions of hours of professional and amateur movies and video, I feel Sutton's work will live as a prime, acutely distilled example of American's inner lives exposed, bleeding out across the framework of gentrification, social unrest, gun violence and outlier cultures who can't quite articulate their revolution; their need for expression of a new kind.

Working for the first time with cinematographer Helene Louvart (best known for Wim Wenders' Pina), Sutton treats suburbia as a triptych landscape, rising into the dream of the moment, while tackling the curious lure of both frontier past and derelict future. The lawns of crusty bungalows grow high. Stretching out like spider's webs, parking lot lights flicker, silent witnesses to coming rage. Louvart's camera tracks along apartment walkways, sidewalks, beach fronts, highways, framing our wanders and dreamers, the tormentors and tormented, in clean full shots, painting them as targets for our sympathies and our weariness.

The young women and girls of the picture are often lensed with a very conscious if slightly abstracted voyeuristic touch, subtly addressing the often default objectification females on film. The men and boys are often framed from behind, the camera slowly pushing in on their tensing shoulders and necks.

What Sutton is addressing here, ever so carefully, and without overexposure, is why the medium often defaults to merely sexualizing women and depicting men in the throes of their violence. Is this actually the cinematic legacy we are passing onto our youth, and how much of that is a larger cultural reflection that leans to something of a dispossessed misogyny? Such questions linger like a summer breeze well past sunset.

Key collaborations that help hone the film's dreamy, if ever wary mood come from editor Jeanne Applegate (formerly of Pixar, and most recently on Sebastian Silva's loopy Nasty Baby) and composer Maica Armata. Applegate and Sutton make cuts only when absolutely necessary, allowing the breath of the shot to land and expand out across the screen in beautiful long takes. This allows for the undercurrent of tension to ebb and flow with a frightening accuracy of just when and where it rises and falls and how it hits you. Sometimes a cut comes as an absolute relief to the utter vice grip of a scene, while in other moments it lulls us into a serene, meditative place.

Armata's dissonant guitar score, along with her original songs, work in much the same way. As Sutton has noted in Q&As, they also add a cold note of narration -- like a greek chorus -- to the unfolding stories on screen. The how and why and what kind of music that plays is so crucial to the makeup of the film that my original headline was in fact "Ballad for the New American Apocalypse". The film is also then very much a dirge; for all the past shootings and the ones to come; for all their victims and the shooters themselves.

Upon my two viewings during the 2016 Sundance Film Festical, I declared Dark Night as the first great film of 2016. By the end of the year it ranked as my favorite non-documentary work from America. So with such declarations comes a great swell of desire on my part to talk to as many people about the film as I can. This review is a first step to championing such brave and humane work. Dark Night is a meaningful document of America at a seemingly seismic crossroads. Whether or not you believe art can lead to healing and education as I do, I look forward to seeing what a proper theatrical and future VOD release holds for the film and what kind of conversations and considerations it will inspire.

Review originally published during the Sundance Film Festival in January 2016. The film will open in New York on February 3 and in Los Angeles on February 9 with further cities to follow.