Review: 20TH CENTURY WOMEN Rocks the Roost

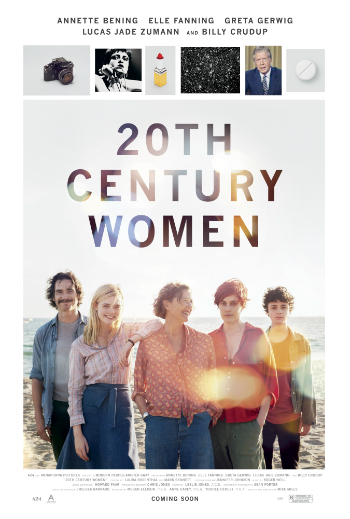

Writer-director Mike Mills' late 1970s semi-autobiographical comedy drama stars Annette Bening, Greta Gerwig, Billy Crudup, Elle Fanning and Lucas Jade Zumann.

You must remember this...

Filmmaker Mike Mills remembers a lot of things. His own life is the source material for his films. 2010’s Beginners was about his rough relationship with his father; now, 20th Century Women is about him growing up with his mother.

Darkly comic, brutally honest, deliciously awkward, and provocatively “other,” 20th Century Women casts a literary tranquility all its own. As a late-1970s period piece, its sense of place and time, its careful quotations of other books, songs, and movies, the almost hypnotic, Philip Glass-lite -- in a good way! -- score by Roger Neill is compelling. The lifestyle of all surrounding characters as transient yet not going anywhere, the quality of the tag-team narration by both mother and son… Beautiful.

Annette Bening is Dorothea. “She was in the Great Depression,” her son Jamie would say to explain away certain eccentricities. It's true, as it explains everything and nothing in one fell swoop. Earlier in the film, he paints a more fulfilling, if scattered, verbal portrait of his mid-fifties mom: “She writes down her stocks every morning. She smokes Salems because they’re healthier. She wears Birkenstocks because she’s contemporary. She read Watership Down and learned how to carve rabbits out of wood. And she never dates a man for very long.”

Bening rocks a greying, disheveled head of hair, and does indeed smoke like a chimney. Her character is persistent in enabling her and her son’s survival, yet completely at sea in the changing world all around her. She’s open minded, but she’ll never “get” punk rock. It will get her, though. (Or at least, her car. See the film.) She’s a proactive woman stuck in a reactionary role. It’s a laser-like performance by Bening, one of the year's best.

The punk rock revolution is brought into the house by pink-haired, punky cancer-sufferer Abbie, played exceptionally by Greta Gerwig. Between this and Jackie, Gerwig has effectively shed her “Gerwig-iness” that, while charming to a point in all those Noah Baumbach films and (ugh) their imitators, has been wearing increasingly thin.

Abbie is a fragile and self-absorbed photographer/artist who’s already dismissed her own future. She clings to of-the-moment feminism and feminist theory, although she’s not militant about it. Her influence on Jamie is palpable and amusing; who knows how formative it will be.

She’s sleeping with William, a man’s man and earth-mother all rolled into one sweaty, lusty, handyman mechanic/hippie. It’s Billy Crudup, who’s also in Jackie, and also having a great year on screen.

This character, though, could do better for himself if he’d learn to trust and commit. And maybe laugh at himself. For obvious reasons, he’s not a '20th century woman.' Yet, here he is. He’s got a wandering eye that betrays his soulful qualities, but those are ever undercut by his New Age and clairvoyant-y comments. He gets laughed at, but he’s also getting laid. And none of it is getting him anywhere.

William is dismissed as a possible father figure for Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann). As co-narrator and Mills' own surrogate, Jamie is the clear crux of the film. "I know him less every day," Dorothea matter-of-factly tells the viewer.

As an emerging young man in a wildly matriarchal West Coast household, his tendencies toward contemporary feminism and the arty side of punk rock (lots of early Talking Heads music) are also unique qualities among his friends. He soaks it all up and holds his own surprisingly well, particularly amid his hormonal frustrations with Julie, a pretty young broken flower played by Elle Fanning.

She regularly enters Jamie's bedroom through his second story window, spending the night in his bed. It's all purely platonic, much to his libidinous chagrin. She's out there messing around with other guys, then decompressing about her unsatisfactory exploits to him. Trapped forever in a very rigid "friend zone," he wants to both help her and have her. Again, the film gets this tension just right.

The pop culture and societal tapestry that informs the world of 20th Century Women is vital and well woven. Beautiful asides from sources ranging from Judy Blume to Jimmy Carter, with an assist from the great film Koyaaniqatsi, carry weight that makes their resonance in this world relatable. Maybe if Carter's maligned “Crisis of Confidence” speech bore Roger Neill's score, it would've landed as intended.

Far less unknown is the film Casablanca. The tragic romance for the ages is evoked both in this film and Damien Chazelle’s La La Land; for different reasons, each. Yet, the film rings as true as ever in these troubled times, as well as the troubled times gone by. Because the problems of two people don't amount to a hill of beans in this world. Not now, and not then. Except, yes they do.

With 20th Century Women, writer-director Mike Mills has delivered one of the great late surprises of the 2016 movie year. Funny, resonant, universal but specific, the film may not always be comfortable, but that's what makes this coming of age semi-autobiographical piece a worthy read. Do not miss this messed-up, ugly, gloriously intoxicating American beauty. It is to be remembered.

The film opens today in select theaters in New York and Los Angeles via A24 Films before expanding in the coming weeks across the U.S.. It will open in Toronto on January 13 and in Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Winnipeg, Halifx and Ottawa on January 20.