Fantasia 2016 Review: FURY OF THE DEMON Offers Film History With An Occult Twist

Suspension of disbelief is a critical element to the pure enjoyment of a movie. Whether it is the premise of the story, the matte lines (or digital uncanny valley) of the special effects, or even character motivations, a good storyteller must overcome our awareness that we are watching something created in order to achieve full immersion into a film.

But when it happens, it is its own kind of magic, audiences collectively under the spell of the film can laugh together, cry together, get righteously angry about an aspect of society, or perhaps, enter a state of shared hallucination or dementia. I mean, look at how the new Ghostbusters film is driving people bonkers on the internet, on both sides of the political chasm it seems to have opened.

Filmmakers should be aware of the power they wield, and some of the savvier (and devious) ones know they can tug the threads of suspension of belief delicately, to offer careful falsehoods mixed with gut-level truths and confidence building images to achieve this effect in interesting and exciting ways. Think of what William Friedkin did to his audiences' fears and beliefs with The Exorcist, or Orson Welles' fiendish manipulation of film structure and gamesmanship with F For Fake, or Myrick and Sánchez's subversion of the documentary form with The Blair Witch Project.

Think of the entire propaganda arms of so many countries and the winning of hearts and minds through the moving image. Quentin Tarantino had a bit of a heyday the the metaphor of the power of cinema (both the content and the physical object) by having his heroine use the actual nitrate prints of films (propaganda and otherwise) to physically destroy the heads of state of the Third Reich and completely re-write history into fantasy in Inglourious Basterds.

Movies of all kinds have delighted and amazed audiences all the way back to the dawn of the medium. As culture goes, the wide accessibility and low cost of the movies was akin to the 19th century vaudeville, where short comedies, dramas, freakshows and musical acts shared the spotlight with the ever celebrated stage-magician. Many of the performers would in the 20th century make the transition to filmmaking.

In the case of both popular art forms, the tales and legends around the actual artists, both celebrated and infamous, are often as captivating as their actual performances or body of work. Because any stage show was performed live, evidence beyond a few black and white photographs or those fantastically illustrated playbills and the style all but disappeared in the 1930s. The ephemeral nature of that art only increases the value of the myths and legends of the day.

The same can be said earliest period of motion picture making, tucked into a furious and volatile period of the last five years or so in the eighteen hundreds, so many inventions were on the cusp of blooming into the beginning of the next century. Films were these single reel shows, free of editing or splicing, and the art form was the playhouse of innovators and oddballs, pioneering geniuses, ambitious entrepreneurs, and no small shortage of crazy people.

Movies were considered a trendy fad that would soon fade, and thus much of the work was made, exhibited and promptly lost. Like those all but forgotten stage delights, most of these films had people talking about them (remember film is only a couple generations of humanity in its entire existence), and yet enough of them have been preserved, stored and restored, to put our imagination of what has been lost into concrete and more exacting terms.

Film lovers get deeply excited about the possible discovery of a lost or forgotten (or butchered) film, like the full 462 minute version of Eric Von Stroheim's Greed, or Fritz Lang's serial, The Spiders, this extends to not-quite-made pictures such as Stanley Kubrick's A.I. (eventually made in full by Steven Spielberg) or Welles' The Other Side of the Wind (currently a major editing/restoration effort after 40 years on the shelf).

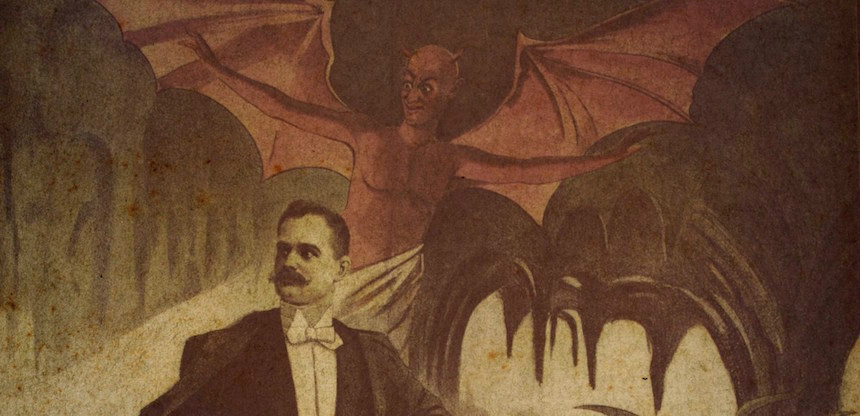

OK. That was a long intro to review of a relatively short film. Fabien Delage's La Rage Du Demon is a 1 hour documentary about he discovery of a lost Georges Méliès picture. The prolific French illusionist was kind of the Nikola Tesla of cinema special effect techniques, and one of the key starting points of the medium. Like Tesla, after kickstarting a sizeable part of the practical and imaginative elements in his field, he fell into a kind of poverty and obscurity (pidgeon feeding and loneliness for Tesla, toy and confection retail for Méliès) until finally being re-discovered and celebrated.

If you are reading this review, you are likely familiar with his most iconic image, that of the rocket-ship embedded in the face of the moon. Méliès was and is considered by many as esoteric wizards of unfathomable genius, and the great grandfather of all special effects and fantasy films in the history of the medium.

But again, I digress. And if I keep doing this, it is because that is the nature of Delage's doc - erudite flights of fantasy offered by well known film enthusiasts, scholars and directors (including Méliès great-great granddaughter Pauline) from around the world, who serve as talking heads and guides to the work of Georges Méliès, the company he kept and the mythic stuff of his work. One of the side-effects of this film is that it is a kind of gussied up early cinema history in a tight box. It's makes the drier kind of Film101 textbook approach come at you. But beware (or embrace) the landmines of this approach, because Delage is an enthusiastic trickster too.

The particulars which involved a screening of the eponymous Méliès film, La Rage Du Demon, thought lost, but recently discovered in a dusty archive, has the odd effect of driving few the people who manage to see it into fits of unconscious hysteria and rage. Screened in 2012 by recluse patron of the arts Edgar Allan Wallace in an exclusive, private event for a select group of celebrities, producers, scholars and socialites, the screening broke down in chaos, and the print once again disappeared. Eyewitnesses of the event recount their strange experience for the filmmaker.

A similar incident is discussed, a documented one that occurred in 1939 when the film surfaced and was screened in front of the Tod Browning feature, Miracles For Sale. And there are stories of yet a third incident in 1897, when La Rage Du Demon was first made and released to analogous audience craziness, resulting in three deaths in the auditorium.

Anyone who has taken an early film course will immediately mythic lore of The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station, the Lumière Brothers' infamous short of a train driving at the camera, which is said to have scattered audiences out of the cinema for fear they would be run down! Another digression, dammit! Albeit one that is brought up in the film.

Suffice it to say that conspiracy theory and film history have always had an amusing double-helix about them, and Delage has a lot of fun with his particular kick at the can. His interviewees have just the right balance of sober and enthusiastic credulity, and their theories and investigations are a satisfying blend of professional curiosity and Coast-to-Coast AM Radio.

A large portion of the film spends time convincing us that La Rage Du Demon is not, in fact, a work of Méliès, but rather a shadowy occult protégé of his named Sicarious, a faustian character who frequented underground saloons where the drinks were served on coffins, and was possibly responsible for the murder a girlfriend before disappearing himself. Yes, somewhere in there Sicarious managed to find some spare spare time to 'invent' film editing before Robert Paul and Edwin Porter.

Delage is not above tipping his hand (and his hat) to film history, making this a fun if slightly inside joke to enthusiasts of the history of narrative film. He also dabbles in some classic witchcraft scientific-lore, with one off-the-wall scholar suggesting ergot or mould in the cellulite print being scattered into the auditorium each time the film runs through the sprockets and arc lamps of the projector causing a kind of biological or chemical psychosis.

Lovecraft's portals of perception pop up as well at one point, indicating Delage's thesis that film and magic is the stuff of dreams and the unknowable mysteries of the universe. He grounds this by shooting the interviews as workmanlike as possible that might even hide in plain sight, his sense of the mundane-campiness in how doc filmmakers have their subjects places in the frame in front of museum displays, cinema seats and other meaning laden image systems to earn audience confidence.

Sitting comfortably in the interior space of a triangle bound by Peter Jackson's Forgotten Silver, Benjamin Christensen's Häxan, and Martin Scorsese's Hugo, Fabien Delage's mock-doc on the subversive power of cinema also shares a healthy portion of creative DNA with Theodore Roszak's wonderfully subversive novel Flicker -- a kind of literate Da Vinci Code for cineastes (and a jillion times better than the Dan Brown novel) -- that elevates the academic endeavour of archiving and preservation to the point where it flirts with being sexy and dangerous. Perhaps, in the end, this is the most accomplished act of suspension of disbelief!