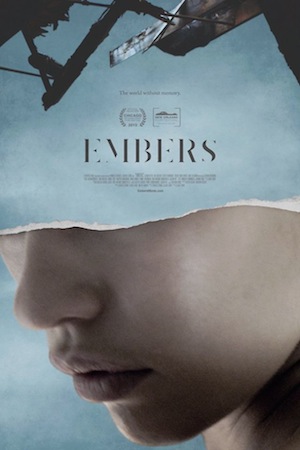

Slamdance 2016 Review: EMBERS, Fresh And Fascinating Sci-Fi

When we talk about ourselves we are building the conversation off a varied, often strange and impressionistic collection of moments stored over the culminating years of our lives. When we talk about ourselves, we talk about our memories. The time you fell off your bike and scrapped your knee. How did that make you feel, and what does that memory of that feeling do to you now? The moment when a grandparent died. How did that make you feel? What about a kiss, a kindness, a cruelty... that first time you fell in love with someone. Memories and feelings are often so closely related -- with societies and cultures essentially acting as the ultimate legacies to memory -- the question arises: can we truly understand or know existence without one or the other?

Who are we then without our personal memories, the narratives we've built up over a lifetime. What if everyday was a reset, without the encroaching towers of culture and art and judgement? Who would we choose to be on that day? How would we feel?

These are the questions that burst forth from the core of Claire Carré's debut feature Embers, a heartfelt science fiction yarn that works as a timely allegory on our culture of volume and over-saturation, and as a invigorating hypothesis on the fluidity of identity and the nature of self and of freedom. Carré's measured and curious filmmaking follows a philosophical tone more reminiscent of Richard Linklater and Wim Wenders rather than most genre familiars.

Embers' story structure and world are presented in such a simple way as to be quite striking and involving. The basics are as such: Survivors of a global neurological epidemic wander through a post-memory world, waking up everyday into another tabula rasa. It should be stated that while personal histories and identities (knowing your name, where you live, what you do for work) have been erased by the virus, procedural and emotional memory, that kind of sense memory (how to cook, how to clean yourself, how to kiss, how to speak) remain mostly intact. In turn, short term memory and experience can be sustained in this world as long as you give focus to it. Though if you so much as fall asleep, that experience of self, of that day, will be lost forever.

Carré and co-writer Charles Spano frame this new reality across a patchwork of stories, some that literally interconnect, while others merely link by theme.

The lyrical and tender heart of the film lies with Jason Ritter and Iva Gocheva as a man and a woman who awake side by side; unfamiliar faces in an unfamiliar bed. Are they lovers? Possibly married? They both wear the same bracelet. They must know each other. They must be in love with each other. And so, as two people falling in love for the first time or the fiftieth, they set out across a blighted urban landscape. Meanwhile, teenage Miranda (Greta Fernández), is quarantined with her father. They are possibly the only two humans left alive who are unaffected by the virus. While her father makes all attempts to preserve the art and culture of the past, Miranda is left floundering. Her existence is barely more than a series of exercises and rituals which do not change. In this regime of no-flux, she is becoming restless.  Secondary stories include an older professor (Tucker Smallwood) who furtively, and perhaps fruitlessly, puts the puzzle of what happened to the world together, hoping that solving such a mystery will yield a cure. A silent boy (Silvain Friedman), seemingly with untouched memory but lacking speech, eventually arrives at the teacher's doorstep. As an interesting emotional parallel to the peaceful and curious nature of the boy, our final narrative follows a young man (Karl Glusman), racked with anger and violence. He is a flame raging on an already burnt plain.

Secondary stories include an older professor (Tucker Smallwood) who furtively, and perhaps fruitlessly, puts the puzzle of what happened to the world together, hoping that solving such a mystery will yield a cure. A silent boy (Silvain Friedman), seemingly with untouched memory but lacking speech, eventually arrives at the teacher's doorstep. As an interesting emotional parallel to the peaceful and curious nature of the boy, our final narrative follows a young man (Karl Glusman), racked with anger and violence. He is a flame raging on an already burnt plain.

We often relate a good deal of action and violence to the sci-fi genre. This is perhaps even more particular in the post-apocalyptic sub genre (One has to look no further than the intimidatingly excellent Mad Max: Fury Road for that). Yet even smaller, headier sci-fi offerings, such as Ex Machina, can end in a cacophony of what I sometimes feel is unnecessary violence; violence that seems to wash away all that has come before it, perhaps unintentionally stating that humanity's primal base is to survive by use of force. What's interesting to note here is that, despite (or perhaps because of) the violent man's story line, Embers posits the notion that humanity's primal base is actually that of love. Considering the above, this is a rather refreshing notion, and one that acts as a great signifier of just how varied and potent the genre can be. For when at its most human, and thus I feel at its best, science fiction is about just how far our capacity for empathy can take us.

Embers may not offer its truths on a mind-blowing and cosmic scale, but what it stands for is very much of that spirit, and of that range. It is a film that reaches deep inside humanity, inside our collective soul (a collective history beyond memory), searching for that basic instinct, that inherent self beyond self. Once found, it then arises with open arms, ready to embrace the moment. Ready to embrace the universe.

Embers, as the closing night film at the Slamdance Film Festival, screens tomorrow, 1/28 at 5:30, at Treasure Mountain Inn, Park City, Utah.