Miguel Gomes On Desires And Fears And People In The ARABIAN NIGHTS Trilogy

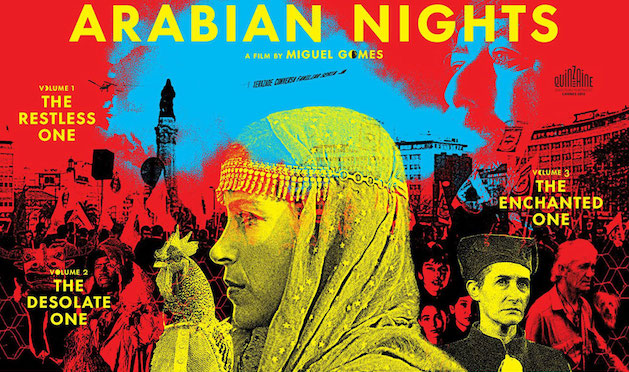

The gargantuan-sized Arabian Nights, presented in three 2-hour volumes, has been playing festivals around the world and rolling out commercially as well. The second part of the trilogy is even Portugal's submission for the Best Foreign Language Oscar. When I caught the film in its 6-hour+ roadshow format back in September, it was only a fraction into the film when I knew this would be the best cinema experience I had in 2015. Sitting here in the new year, on the eve of the Toronto release of the film (at TIFF Lightbox), this has borne out to be true.

Thus, when the opportunity arose, it was a pleasure to be able to converse with director Miguel Gomes via Skype from across the Atlantic in Lisbon. Patient, and impeccably polite, with a penchant for substituting the word sensation for feeling, Gomes comes across as someone who knows what he is seeking when it comes to an idea, image or a visual stratagem. And Arabian Nights is an efficacious fountain of all of these things as it engages far ranging subjects including his Portugal's lengthy austerity-crisis, the cause & effect in administering justice, libertarian criminal folk-heroes, the nature of storytelling, and the minutiae of training original birdsong to chaffinches.

Below is a transcript, abridged and edited for time and flow, of our conversation lasting somewhat past thirty minutes (or for a different measure of time, in his case, two and a half cigarettes.)

Kurt Halfyard: I know you have had this question a thousand times, but perhaps I have a somewhat different spin on it. When I saw the Arabian Nights Trilogy at the Toronto International Film Festival, I saw it as a single viewing, with a full credit block and 10 minute intermissions between parts.

Miguel Gomes: That is a tough thing to do isn't it? For me, that is a tough thing. I have the sensation that each film needs an intermission. A real intermission. I have heard people saying that they have seen it both ways, for example, one volume a day with a significant gap between, and, like you, all three in a row. Some of them did prefer to watch it together in a row.

I am not sure if you are aware of Anurag Kashyap's Gangs of Wasseypur. It is a six hour socioeconomic crime epic made in northern India. Netflix recently purchased the film to show on their platform, but they are re-formatting it into a miniseries, either to be binge-watched as one does, in a marathon viewing, or in six parts instead of the theatrical two parts; that is, potentially to be watched in significantly smaller units, controlled by the viewer. How would you feel about Arabian Nights being handled in this format?

I think it is a good thing, because the film will be available in another way. That personal question directed at me, as a viewer, may not count for very much, but for me, I do not like to watch films on a laptop. I am getting older, and so, I have this conservative idea that films should be seen on a big screen, in a theatre. But I like some things about this idea. I like the idea that the viewer can change the order, or can take a break when they want to. Inside the cinema we are completely immersed in the film; it is a completely different experience. The sound is completely different, and the image is different. And yet, I am happy with the other things you can get by watching it another way.

The Arabian Nights trilogy was a film that very much defied my expectations of what such a film might be. I do not even recall what my expectations were, beyond the austerity and Scheherazade storytelling form, but they were certainly defied! Over the course of the experience, I felt there was a rhythm established in both humour and how you were working as a filmmaker. And even that rhythm, as things went further along, would be pleasantly flouted in new ways. I wonder what your sense was towards timing and transitions when constructing such a large collection of disparate stories and styles together. Was there a comedian's (or magician's) philosophy of doing one thing with one hand, while doing a more subtle, or even contradictory, thing with the other?

For me, it was important to have diversity. The way you place things, and change the tone of the film from tragedy to comical absurdity, was very important. I thought the potential richness in the film would be from these shifts in tone. This can be most unstable for the viewer because now we are used to the experience of cinema to be consistent in tone. To be honest, most of the times, I get bored with this. I think films should be in movement and I think the viewer should be in movement with the film.

Sometimes we talk about the question of whether a film was a slow pace or a fast pace. For me it is not the length of the shots that define how fast or slow a film feels, it is how you travel with the film. What is the movement that the film is doing, and what is the movement within the viewer. It was very important to me to have all these different paces, and all these different chronologies. I take pleasure with these changes within the structure of the film.

In the prologue of the first volume, it was very important to establish the rules of the game. That it would be about people who really did lose their jobs, and that it would be like a documentary, a much more directly connected version of cinema to reality, without filters, without narrative strategies right beside the strange-acting filmmaker running away from his own film, and also feel like a John Carpenter film, with these men with guns fighting a plague of wasps - apocalyptic cinema. The film had to have space for all of these things. You see them all together in the beginning to share the rules with the viewer and that can then make a journey together though different ways of cinema, reality, storytelling and moving through Portugal.

The journey itself is modulated by the musical cues, repeated songs like Perfidia, or birdsong. It is almost a way of helping the audience change mood? Maybe you can elaborate on that.

Even if the film is not an adaptation of the book, Arabian Nights - there are no tales taken from the book into the film - it is an adaptation of my personal impressions reading that book. That means, this book, and the film, should be a wild labyrinth. In Arabian Nights, you will read a tale, then 500 pages later, you will get almost the same tale, but with small differences. You have the sensation that you are returning to a certain element. You recognize this element, but it has changed over the span of time. It was important, for me, to have something of this. To re-encounter the same situations, the same songs, but when they re-appear, they are new. A new sound, a reggae version, a big-orchestra version, the Mexican version, you recognize Perfidia, but you also see the differences. This comes directly from the structure of the book.

And the way you use text on screen? The way it is put up, and where it continually comes into play. This had a musical feeling to me as well. Even the end-credits have a full index of the film sorted by time, like liner notes on a record. I have never seen that done before, and it was delightful. I felt the text was almost a character in the film.

It should. We used what I like to call a 'silent voice over,' because you can only hear it in your head. It is not said by a character. When I was editing the film, the moment where I tried it for the first time, I had this sensation between putting it over by image or by sound. I preferred the image. To save the [audio] for the other sounds. It was less imposing to use text than a voice. By the last volume of the film, it starts to resemble a book, with an increase in text. As soon as we started doing that, we said, "let's go in that direction."

Obviously the movie is dealing a significant economic crisis and a specific Portugese national character: people losing their living, and all the pressures and constraints that come along with that. But what I gathered from the specifics of film was that it is about the simple dignity of work. And that government imposed austerity measures stripped that away. Even the bizarre notion of rough, hard men teaching chaffinches new ways to sing songs in urban poverty, that there is a discipline and dignity that goes into even the strangest of human efforts.

I have the same feeling. It was mostly in the way that the government was talking about the situation that was offensive. There were lots of people losing their jobs, and we heard the Prime Minister of Portugal saying ... forgive me, i don't know how to translate this ... "Don't be such as sissy." I think this was absurd! You cannot do what they were doing and at the same time disregard what is happening to people. It was an absurd moment, and a painful one.

It is very important to shoot things I like. Even if the characters are a bit childish, or a bit ridiculous, in some way, somehow, they should keep, or should have, this dignity. And so, it is my job to do it that way. This is connected with the things I like. I really enjoy The Rules of the Game by Jean Renoir, which deals with characters on the verge of desperation, and they are doing very foolish things, they are very comical. But you always have the sensation that the director has a connection with them, a sympathy for them, even if he is showing them doing absurd things. I got the message from that film, I cannot do it any other way.

On the other hand, I also feel that there are some power structures that the film is quite savage how it deals with these things, I'm thinking "The Men with Hard-Ons" chapter for instance, or the empathy of the couple committing suicide in a later chapter. The film often feels like a marriage between Monty Python and Vittorio Di Sica.

The humour comes from me, i guess, it is part of my personality. And the film is how I look to the world in a fluid and natural way. It is also, if you think about it, a good strategy to avoid emotional manipulation, and not to force the viewer to decide what they should think or feel. This is a good filter between the film and the viewer.

You say in the prologue as the onscreen filmmaker character, that abstraction gives you a headache. I found that despite being so specific to Portugal, Arabian Nights very much captures something universal. In the way people pursue things as individuals, and en mass, meaning a country. Have you read the various cultural reactions, the foreign reviews of your film. Do they surprise you?

I do read some of them. I was a film critic, and that changes my perception of this issue, now as a film director. I see other filmmakers get, I have the impression, really angry when they read a review that they do not agree with at all; or they are really happy. Maybe I have a bit more distance. When I was a critic, I wrote about films, and seeing films with other critics in press screenings, as you know, there are lots of way to watch a film. There are very different reactions. I was used to this kind of diversity. I was much more close to the way some of my fellow critics saw films, and distant from some, as well. It was not something that I feel in a very natural way. There are so many ways of watching a film, or liking a film, I have the impression that cinema was from the start is and remains sharing an experience with lots of people that I do not know. By leaving the theatre, we are all having different kinds of reaction. There is a collective kind of thing, which is great, but at the same time, it is very personal, only you and the film. The film was either talking or not talking to you. Everyone has very different interests, or humour, on sensibility. Basically, everyone is different, and different reactions are very normal.

Was there a story or an idea you wanted in the film, but circumstances prevented it from happening?

There were lots of ideas, so many ideas, we had this crew of journalists that were working with us, to provide the basis for our stories. There was one that we really wanted to do. A situation involving the many Brazilians in Portugal. The were leaving at that moment because of the crisis. They were leaving in this huge cruise ship. It was less expensive to bring their furniture and belongings into a room on a luxury boat, beds and drawers and things mixed in with the pools and parties on the ship. We wanted to do this, we tried to get a boat for a whole year. But it was impossible. We also had this map of Portugal, and we marked the spots where each of the stories were. We had the sensation that we were not covering the whole territory.

In the south, there is this landscape that I didn't use in the film, it is very different. We were working on a story to film there, we almost succeeded. It was about a guy who went a little bit crazy, he was working in a church, he thought he was underpaid by the priests. He started to draw swastikas all over the church, and he was doing sabotage in the church all the time. By the end, there was this transmission of christmas, a tradition on live television of mass. This guy went so crazy about the crisis that he went to war with the sacred. I really wanted to shoot that, it was a wild story,

But there is always a day when my producer says, "no money." We had two more stories to shoot.

After doing a film of this size, would there ever be an urge to make, say, 'Arabian Nights: Appendix A'?

No. I am fed up with Arabian Nights! I have enjoyed finishing the film; it was very tough to make this one. When we finished one story, we were starting on another, and the work was non-stop. There was a story that we started to research, and I said, "Stop. This can be a film on its own." Maybe one day I will come to this story.

Story telling is storytelling. You intimate in Arabian Nights that stories are the desires and fears of people. How do feel about genre?

There are so many worlds within cinema, over a hundred years and there are so many codes and references. We have to work with all of them. I am aware of genre codes, such as the American musical comedies in the 1950s. That was another society, another moment of film history. We cannot do exactly this thing, but we have the memory of them. It is important that we can use these mechanisms in another way; in a way that we have to find out.

On the question of the fears and desires of people, it does create something I think is very crucial. In Arabian Nights, we have space for real stuff, but also for the imaginary. The imaginary comes from living in a certain moment, and wanting something to happen, or being afraid of something happening. The Imaginary comes out of our experience of living through situations. Reality and imaginary are bound in a very tight way for me. You have to do cinema with both!

You mean along the lines of Picasso's quote that "Art is lies that tell the truth."

That was Orson Welles, no?

From F For Fake? It is such a good quote. Who knows how many people appropriate it.

I don't think it was actually Orson Wells, but I think he could have said it. Yes, I think cinema should definitely not look as life. I do not want to be someone who is angry with the state of cinema, but sometimes I am disappointed when contemporary films spend all the filmmaking effort to achieve something that looks like reality. When it is shot in a sort of reporters kind of way. It's bullshit. We know it is a film, don't take us for being stupid. Sometimes it is good to show the artificial worlds of cinema with the hope that we are talking about real problems, or this has the connection with peoples lives. We want truth though.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.