Review: BIG EYES Goes Bleary In Spite Of Itself

Goths and mopes responded en masse to his production of The Nightmare Before Christmas, families responded to his mischievous colorful streak in Pee Wee's Big Adventure. Everyone responded to 1989's Batman. That's the zeitgeist effort that's made him a household name, replete with a collective frenzy for Batman trading cards and t-shirts which ran roughshod on the film itself. He's gone effectively gory with Sleepy Hollow and Sweeney Todd, and frustratingly vapid with Planet of the Apes and Alice in Wonderland. Indeed, when Burton tries to cop himself, he's just another soulless Tim Burton impersonator.

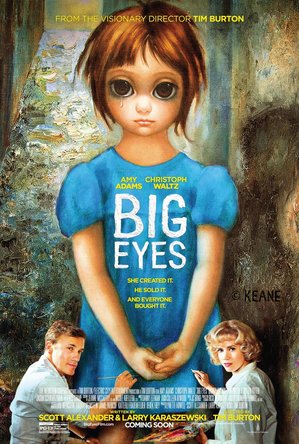

Burton's latest, Big Eyes, is the director desperately trying to climb out of the box he's contentedly spent the last three decades occupying. He's jumped ship from his cozy confines of Warners and Disney to the Weinstein Company, and promisingly re-teamed with Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, the screenwriting pair behind Ed Wood, widely considered Burton's finest film.

The movie tells the story of Margaret Keane (Amy Adams), a timid woman typical of 1950s America in her willingness to be subservient to the male-driven culture around her. But she's also a thinking, feeling painter clamoring for an outlet, an audience. When she meets Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz), the man she will marry and adopt the name of, she believes she's found both true love and an artistic soulmate. Margaret is proven wrong on both counts.

Walter is revealed to be not just a fraud, not just a huckster, but an abusive plagiarizer. What he authentically is, however, is an ace marketer and seller - the likes of which the art world hadn't yet known. Before long, he's not only taking full credit for his wife's work while keeping her literally locked away churning out more and more and more of her paintings of big eyed children and animals, but he's selling them as reproductions, books, postcards, you name it, anywhere and everywhere he can. It's the advent of mass produced kitsch art, and the world can't get enough of it. Whatever soul Margaret is pouring into her many paintings of sad faced optically enhanced cherubs is immediately snuffed by their handling. Never mind their own inherent cutesy grotesque nature...

Big Eyes, like Ed Wood, is a true-life period piece about a misunderstood artist, one who's work has been dismissed, pigeonholed, and over-commercialized. Needless to say, this is territory Burton knows a thing or two about. Hence, the crashing disappointment of Big Eyes. Ultimately, it's not the convergence of any personal statement on behalf of Burton, nor his newfangled attempt at addressing gender politics that surprises most about Big Eyes. No, that honor goes to the realization of just how flat the whole affair is. Never before in his career has the soaring potential and admittedly rare attempt at personal reflection and vision been so snuffed, so blah.

In his attempt to climb out of his predictable-weirdo box, he's sadly fallen into another box. With Big Eyes he's adopted the skin of a Douglas Sirk melodrama, sans the effective bite of one. There's something untrue and confining about Big Eyes. It demonstrates glaringly little evidence of the things we love about Tim Burton, the very things that make Burton Burton - his crafty stylization, his whirling vortexes, his mischievousness, his gothic flair.

In their place we have weak-sauce Weinstein Company failing Oscar bait. (Amy Adams, in a part that screamed with awards season buzz up until anyone actually saw the film, perhaps plays quiet and mousy too well for her own good this time!) Burton and company forsake their own attempt to make a statement about the plight of women in a man's world by allowing the very man who's confined Margaret - a monster of man by any account - to be a grandstanding clown, the pulse of the film, the wrong kind of one-man three ring circus. A certain justice may prevail by the film's fizzled-out, "That's it?" courtroom ending, but there's a harsh improperness that it is Waltz, and Waltz's character, that we come away talking about.

Bigger themes and serious issues never were, and likely never will be, the stuff of Tim Burton. Which is fine - the man does repression, isolation, and introversion better than most, and on a scale most can't approach. Perhaps the disappointing failure of Big Eyes, a miscalculated swerve into the world of mainstream bio-pics, isn't such a surprise, then. There certainly is evidenced potential, though. Look no further than an early visual of Margaret taking a job in a crib factory, hand painting cute cupids onto headboards. The artists sit inside the cage-like cribs, in perfect impersonal rows. Burton's recent comments to Vanity Fair magazine come to mind, in which he detailed the hopelessness of his graduating from CalArts' animation program to working professionally on Disney's The Fox and the Hound - the literal only gig in town for his profession - which had him feeling imprisoned in a two-year sentence of drawing "cute foxes". The entire rest of Big Eyes lacks anything near the punch of this early moment.

On the positive side, the film tells the story of a prominent 20th century artist whom, whether you like her work or not (and many do not), has been long overdue for rightful recognition on this level. Likewise, Big Eyes, in what's missing, helps us see what it is that we like and need from Tim Burton, a film artist who's schtick we've all been taking for granted. Here's hoping he will go on to make something else worthy of Ed Wood, Edward Scissorhands, Big Fish, and Frankenweenie. Big Eyes, like the work of its heroine, is mournfully disposable.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.