Peter Martin, Stuart Muller, Jaime Grijalba Gomez, Shelagh Rowan-Legg, Christopher O'Keeffe, Eric Ortiz Garcia, Jim Tudor, Ernesto Zelaya Miñano and Ard Vijn

contributed to this story.

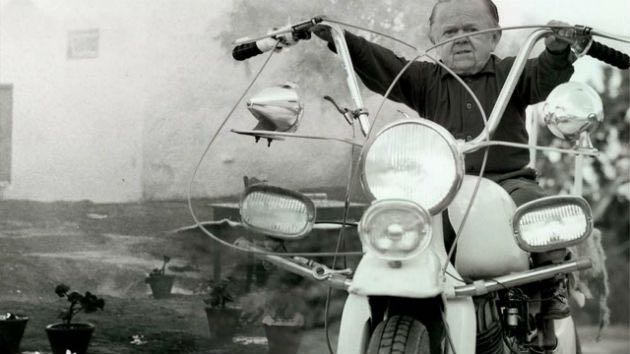

Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970, Germany)

Peter Martin - Managing Editor

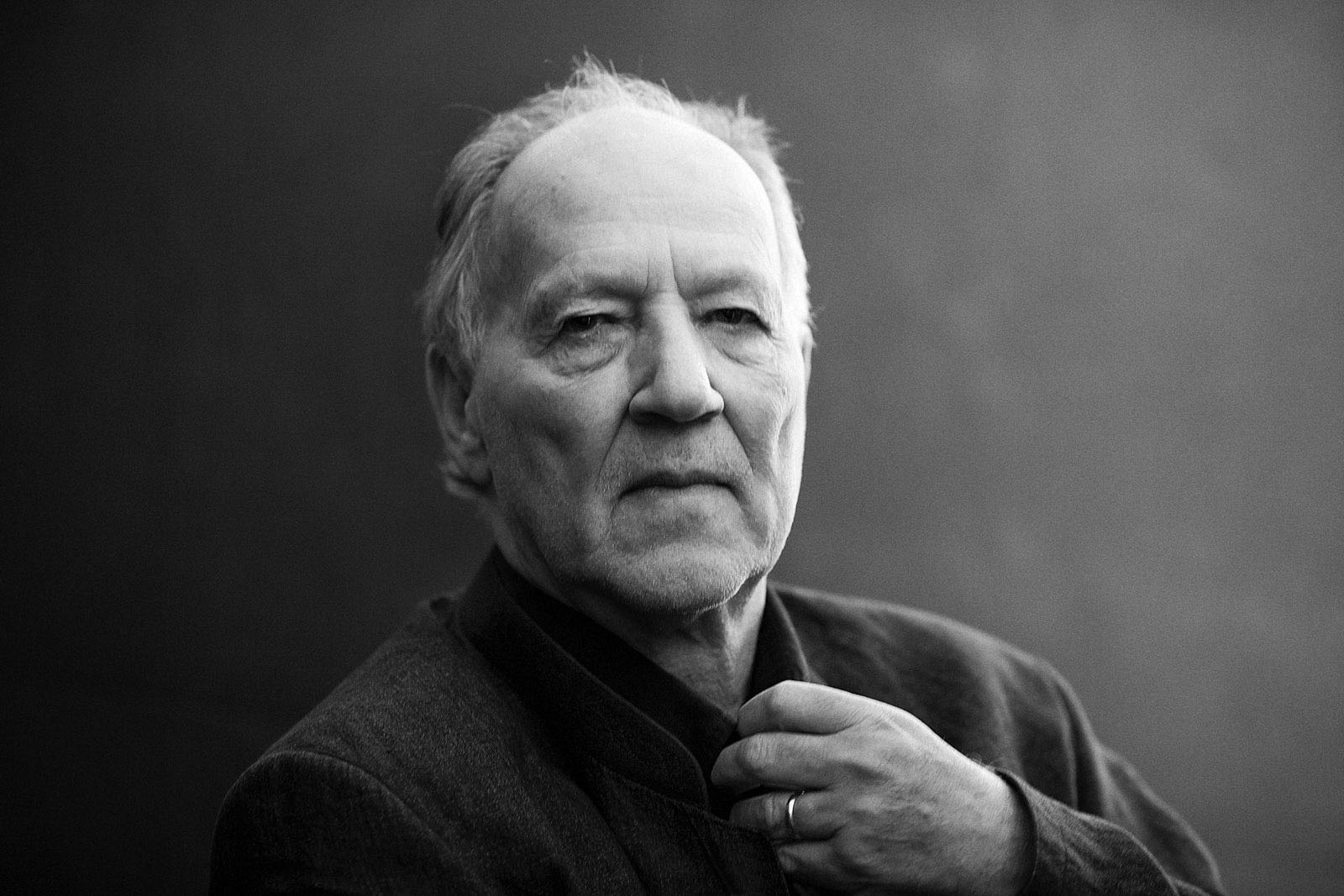

When I began exploring arthouse cinema in the late 1970s, Werner Herzog's name kept popping up as a representative of New German Cinema. But I leaned more toward Rainer Werner Fassbinder at the time, to the exclusion of nearly every other German filmmaker, so my first exposure to Herzog came when I saw the world premiere of Les Blank's documentary Burden Of Dreams at Filmex in Los Angeles in March 1982. Herzog's tortured, magnetic personality mesmerized me, and since then I've always favored his documentaries, which he also narrates and/or appears in, over his fictional creations.

For this series, however, I felt I owed it to Herzog to watch as much of his work as I could, and so to begin I chose this early effort, his second fictional feature, made when the filmmaker was just 27 years of age. It's a dramatic picture with bursts of comedy about a group of inmates/patients in an institution who rebel against the guards and director. And, yes, they're all played by little people.

The film begins in a linear, if mysterious, fashion and then gets increasingly disjointed as the rebels become more frenzied in their activities. Herzog mixes together long, handheld "follow" scenes with leisurely establishing shots; the story itself becomes more compelling as it goes, and the casting of little people adds another level of discomfort for viewers who are not little people. Presented in black and white in the classic aspect ratio (1.33:1), it is aggravating and perceptive at the same time, and made me question my own reactions, a bold re-introduction for me to the work of Werner Herzog.

Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970, Germany)

Stuart Muller - Contributing writer

Even Dwarfs Started Small was Werner Herzog's second film (1970), which is quite astonishing because the film exudes his trademark competence, and confidence, in blending fact with fiction to reach a higher truth. This is already accomplished filmmaking by the young director. It is also challenging filmmaking, confronting the viewer with disconcerting imagery, discombobulating characters, and disquieting themes. Despite the gravitas, the film is unabashedly funny, even goofy, and perhaps this is why I couldn't help but be reminded of Peter Jackson's The Hobbit movies once I started thinking about it.

Admittedly, this is less for Herzog's intended allegory of the necessary tension between control and freedom implicit to the human condition, made manifest through the revolt of an institutionalized band of dwarfs who throw off the yoke of control and progressively devolve into impish hooligans in the absence of supervision. But it's certainly so for the swathe of chaos they collectively wreak, replete with food fights, singing and cheerful rambunctiousness.

In both Jackson's and Herzog's films the dwarfs feel uncontrollable; in defiance of their individual small stature, together they are quite formidable. One can only imagine the tactics Herzog must have employed to rile his band of eccentric little actors up, and sustain their antics for the camera. Looking at the picture above of Herzog during the filming, one can almost catch a Gandalfian twinkle in his eye.

Always one to lead with his heart, Herzog apparently threw himself into a cactus bush during filming in an act of solidarity with his cast after one of the little actors was run over and another caught fire. Hardly surprising when you watch the scenes. This little film is batshit insane and brilliant.

Aguirre, The Wrath Of God (1972, Germany)

Shelagh M. Rowan-Legg - Contributing writer

For some reason, I’ve seen more of Werner Herzog’s documentaries than his fiction films (his Nosferatu remains tied for my favourite vampire movie). So I’ve been playing catch-up with his extensive fiction oeuvre, and was anxious to see another example of his work with Klaus Kinski. Luckily, with Aguirre, I was not disappointed.

One of the themes that seems to run through Herzog’s work (at least from what I can tell so far) is man’s complete ineptitude and useless fight to conquer the natural world. Call it the poetry of despair and futility. While I don’t speak German and was reading subtitles (assuming those subtitles were taken directly from the original English-language script), that poetry was represented in the words, lending the film part of its surreal quality that was less about historical reenactment than a moral and ethical lesson on trying to tame the untameable, or grasp at something that no human has a right to attain.

While there is plenty of action, for me, it almost bordered on a poetic (yes, that word will keep coming up for me) slow cinema, in the slow degradation of the company and their descent into madness. No one better represents this than Kinski, and it seems that in spite of his difficult relationship with Herzog, they bring out the best in each other as an actor/director team. Kinski matches Herzog’s languid, grand shots of the jungle with his own jungle-like performance, determined and yet teeming with dangerous life driven by an intense anger that sets the screen ablaze. I often found myself equally mesmerized and wanting to look away from Kinski’s eyes. Whatever his off-screen behaviour might have been, he was able to hone it to such a degree that he commands the screen, even against such an amazing backdrop. I’ve since discovered that Kinski’s German dialogue was dubbed, but with him, it’s not so much his voice but his eyes that perform.

Even though the film is more of a fictional interpretation of alleged historical events, for such events that have taken place so long ago, perhaps such interpretations are preferable to more ‘accurate’ renderings. I can certainly see why the film remains such a favourite.

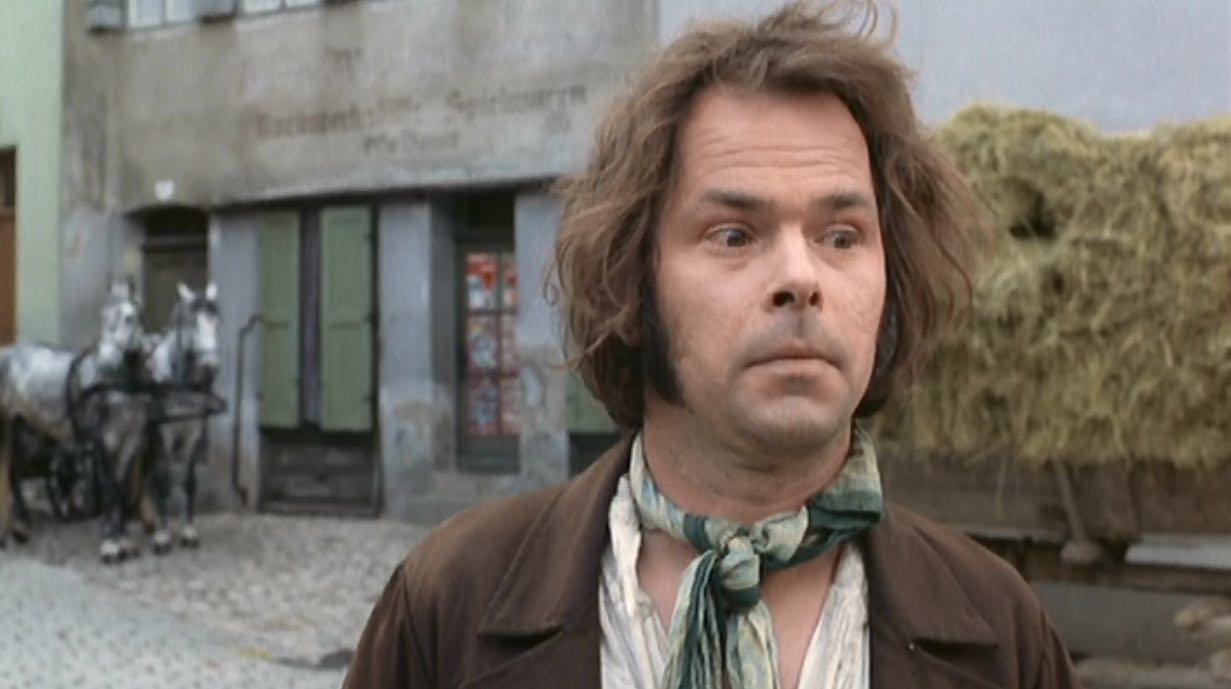

The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser (1974, Germany)

Christopher O’Keeffe - Contributing writer

1972’s The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser opens on a long, static shot that comes across as fairly typical of the director; long grass swirling beautifully, yet violently, under the force of the wind. I was captivated by the image, and with the benefit of seeing the director’s later works, with Grizzly Man particularly in mind, I assumed I would be watching a manifesto on the harshness of nature on a young innocent, but the film is so much more than that. In contains moving episodes of kindness, beauty and a breathtaking central performance, and although there is a harsh and cold cruelty it comes from the world of man and not nature.

Kaspar Hauser’s situation is revealed from the beginning via an inter-title that explains how a boy was found one day in a village, unable to communicate or even walk, who would eventually come to recall being detained in a darkened room his entire life. Throughout the film we follow the young man’s development as he is taken in by the authorities, educated by a kindly prison guard and then by a benevolent man of wealth, forced to learn quickly, grasping to understand the new and confusing world around him.

The performance of Bruno S. in the role of Kaspar is mesmerizing, and from his expression, movements and delivery it’s hard to believe that he is not in fact the foundling boy himself. When the strange young man eventually becomes able to speak, his dialogue and intonation add a depth to the meaning of his questions, of the world and of himself, that might not have been conveyed by any other actor. Kaspar, whose own emotions are often unreadable, stirred in me everything from sadness to laughter, with his blank, expressionless stares and alien movements. Herzog never makes fun of his subject but there are some brilliantly humorous scenes in which the naïve young man perplexes the educated men around him with his novel way of thinking, and it is this exploring of new concepts that is central to the film.

The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser is an incredible story and the fact that Herzog’s film appears as if it is constantly swamped in mist only adds to the mystery of this entertaining and absorbing film.

Fitzcarraldo (1982, Germany)

Winner of the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival

Jaime Grijalba - Contributing writer

I just recently watched my third Werner Herzog film, Aguirre, The Wrath of God, and I was left really surprised with what has been called 'early Herzog', supposedly his best era, though he has put together a filmography to this day that, apparently, is devoid of any major failure. Now, when confronted with Aguirre’s usually paired companion piece, Fitzcarraldo, I was amazed by the way he manages to extract some kind of compelling narrative from extraordinary and sometimes enervating characters, he makes up the strangest of situations that at the same time become believable to the viewer.

Fitzcarraldo is an epic of failure, of the futile, of how someone with a dream, an objective, might not always be the most warming or sympathetic person, though we end up falling and rooting for Fitz. I think that the portrait that Kinski and Herzog paint of this character is one of obsession, something akin to what Buñuel did in the 50s with his various portraits of sicknesses of society and mental breakdowns.

I think it would be accurate to compare Buñuel and Herzog, maybe someone more intelligent than me can connect the dots and find the power that they both bring to the screen through their actors and classical compositions. Here's the thing, there's not much revolutionary in the way that Aguirre or Fitzcarraldo or Bad Lieutenant were shot, I think they are beautiful pictures shot around problems, catastrophes, real hazards done to people, real problems. They become something special because they manage to maintain a classical approach and an ordinate way of exposing information even though everything seems to go against that approach, and that is truly commendable.

Buñuel uses a similar style of blocking and directing in debt to the classic films of Hollywood, but he also subverts it just enough so his films are themselves a criticism of that same style, figuring out and also denouncing how the images work. But enough about Buñuel, let's save it for when Buñuel is the director of the month.

But yeah, Fitzcarraldo is a film about how the futile seems to be the refuge of the losers, and at the same time, the ending is so triumphant that one can't help but smile.

Fitzcarraldo (1982, Germany)

Winner of the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival

Jim Tudor - Contributing writer

Madman. In the cinema of Werner Herzog, particularly his collaborations with crazy-eyed actor Klaus Kinski, the word is most common. In Aguirre, The Wrath Of God, Kinski plays a madman conquistador. In Cobra Verde he's mad into slavery. In Nosferatu, he plays a vampire (is that not inherently mad?). And of course in the documentary My Best Fiend, he is outed by the director as a true madman – one that only another madman could know.

Indeed, in those early years of Herzog's far-reaching global challenges set to film, with his don't-leave-or-I'll-shoot! method of motivating actors, the unhinged overlord Herzog belonged with Kinski. So it should come as no surprise that for their sprawling 1982 burst of crackpot cinema, Kinski plays a madman bent on building an opera house deep in the Amazon jungle. In so doing, they fall mega-timbers and hoist a steamship over a mountain. (All practical! Eat your heart out, D.W. Griffith…)

Whoever says, as it's sometimes uttered, that “it's easy to make a movie about how screwed up everything is, it's delivering a quality message of hope that's difficult”, has obviously never seen Fitzcarraldo. Nowadays, it's safe to say that Herzog has left his gun-totting despotic persona far behind. But whenever he begins a sentence with “When we were making Fitzcarraldo…”, you're assuredly about to hear a tale just as crazed, just as obsessive as anything the film's own grand narrative has to offer. Its making is the stuff of legend, spawning its own integral behind-the-scenes documentary, Burden Of Dreams. (The Hearts Of Darkness to Fitzcarraldo’s Apocalypse Now.)

In a filmography that often finds inspiration in the unfinished (the fate of Aguirre’s mission, the source play for Woyzeck), Fitzcarraldo may be the crowning feat, as it begins in “the land where God did not finish Creation”, and again ends with Kinski's fully-deluded “god” character embracing an outcome other than what he set out for. The opera house may go unfinished, but lo, there is opera in the Amazon! And the insane tension of it all – logic versus ambition, man versus nature, etc. - fully mirrors the film's infamous forging.

Kinski and Herzog were truly two of a kind, those madmen. They deserved each other, even as audiences deserved far, far less. They were one of the great director/actor pairings, their work unique, terrestrial, interior, pioneering, bold, and deathly. And Fitzcarraldo may be the last truly massive epic.

Where the Green Ants Dream (1984, Germany/Australia)

Eric Ortiz Garcia - Contributing writer

From a character that plays a cassette with the Spanish-language narration of some 1978 World Cup matches of Argentina; an old lady who is looking for her lost dog; to a guy that constantly sings Tommy James and The Shondells’ “Hanky Panky”; Werner Herzog’s Where the Green Ants Dream is a film full of very odd bits. Thematically, though, it is clear, direct, and beautifully sad.

In the mid-eighties, Herzog traveled to Australia and showcased an Aborigine group. He also brought a bunch of actors - including Bruce Spence - in order to portray the employees of a mining company. The film then features a story about the conflict between the Aborigines and the white men over a sacred land.

Spence plays the only white man who, ultimately, has a genuine concern for the people that his company is affecting. He tries to explore more about them, their beliefs, and even the peculiar species that green ants are. But acting like this will only lead him to rage and eventual resignation, as it seems the British Empire still has an influence on the territory.

Where the Green Ants Dream is notable for its natural portrait of the Aborigines, and very memorable for the several striking issues it exposes. It will be hard to forget that image of another native clan that never left the place where their sacred tree once stood, even after a supermarket was built exactly there. Or the scene in which an Aborigine speaks a language that nobody else understands, not even the other indigenous people, as he is the last survivor of his clan.

It’s a worthwhile Herzog effort, for sure.

Lessons of Darkness (1992, Germany/France/UK)

Ard Vijn - Contributing writer

I have a confession to make: the Herzog film I wanted to see for this month was My Best Fiend, but less than 20 minutes in I saw the opening shots of Aguirre, The Wrath Of God and my jaw dropped, making me decide to switch to that film immediately. When I told friends that Werner Herzog shoots narratives like they're documentaries (you're REALLY watching hundreds of people descend a steep mountain, you're REALLY watching a madman on a raft overflowing with monkeys...), the response I got was to watch some of Herzog's documentaries, and especially the stunning Lessons Of Darkness. So I did.

Lessons Of Darkness is a 54-minute look at Kuwait, mostly shot right after the first Gulf War, when the border with Iraq was one big wasteland, and the desert was peppered with lakes of crude oil and burning wells. For his film Baraka, Ron Fricke shot some scenes there on 70mm stock, but Herzog easily gets the drop on him even when using "just" super-16. Kuwait looks like a damned place on a different planet, and the long, long shots, often shot from a helicopter, accentuate the madness and sheer scale of what you see.

When the film premiered in Berlin, Herzog was booed off the stage by an angry audience, and accused of mis-using the war's aftermath for the sole purpose of art. The aestheticizing criticism isn't entirely unwarranted: Lessons Of Darkness is more a visual poem and less a documentary. The whole choice of segmentation, classical music and musings by Herzog (obviously more done for effect than for authenticity) is awesome when done with burning oil wells, but he also has victims tell of actual intimate human tragedy, and using that as "paint" was a bit much in my opinion.

That aside, it's visually one of the most impressive films I've ever seen. Knowing that the footage is real is bizarre, as what is on screen is almost unbelievable.

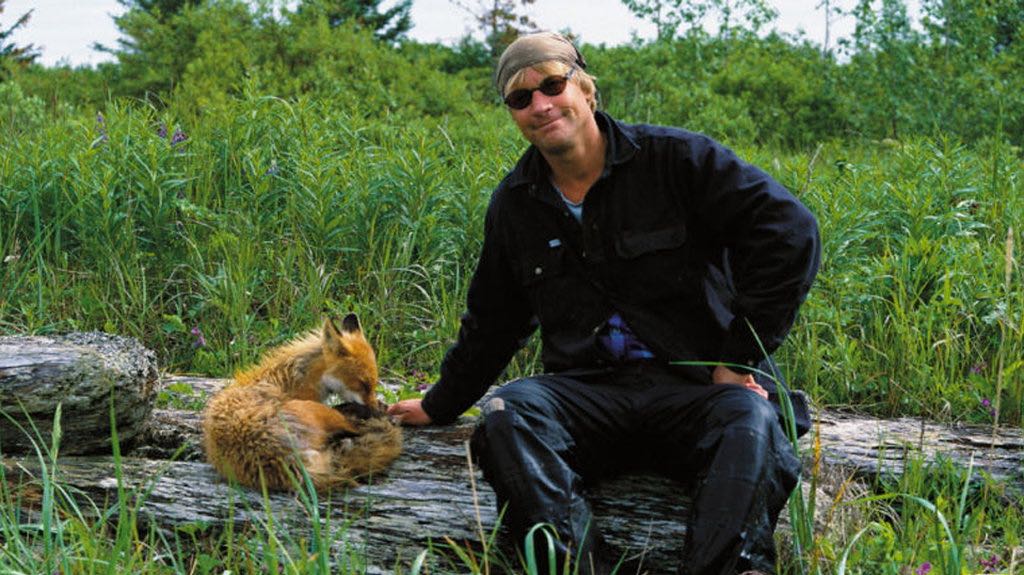

Grizzly Man (2005, USA)

Winner of the Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Documentary award from the Directors Guild of America

Ernesto Zelaya Minano - Contributing writer

Werner Herzog has always defied nature. For proof, there’s the now-famous story behind the filming of Fitzcarraldo. When one watches Les Blank’s Burden Of Dreams and sees the director recklessly trying to move a riverboat up a hill, without giving a whit about his safety or that of others, it’s a portrait of an obsessive man who, like his own characters, hasn’t learned the lesson that Mother Nature is fickle and not to be messed with. It’s easy to see then why he would be attracted to the story of ill-fated environmentalist Timothy Treadwell.

Like Herzog, Treadwell defied nature and paid the price. A man who lived among grizzly bears in remote Alaska, wanting to leave society behind, who thought he was one more amongst peers; all without realizing that Nature would never allow it. Herzog sees something of himself in Treadwell, a sort of kindred spirit in filmmaking; they both had a guerrilla spirit of shooting their surroundings in as real a manner as possible, revealing deeper truths about the world and themselves. But even Herzog had to admit that Treadwell took it too far, and no matter how many years he spent in Bear Country, he would never be one with them.

Treadwell reminded me of Christopher McCandless, another guy who wanted to leave his mundane, everyday existence behind and find himself in The Great Outdoors. A careless mistake killed McCandless, but Treadwell knew what he was getting into and chose not to see it; one could even say that, deep down, he knew what was coming and was content to accept his fate. You can call them both irresponsible nutcases, or you can admire them for attempting something not everyone has the guts to do, even though they secretly want to; both sides of the argument are balanced beautifully.

Herzog has a stoic, serious demeanor and a thick accent that makes him sound like a Bond villain, but this documentary looks past his somewhat intimidating image and shows him as a compassionate and caring person. When he asks Treadwell’s ex-girlfriend to never listen to a recording of his death, there’s a clear concern in his pleas. He knew not to exploit this material, and the result is a subdued and oddly poetic look at the life of a very peculiar individual.

More about Fitzcarraldo

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Now Playing: SCREAM 7 Not So Scary, GHOST ELEPHANTS Not a Myth

SCREAM 7 Review: Well, That Was Brutal

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada