Review: In LABOR DAY, Real Men Bake Pies

That's the tragedy of the new drama, Labor Day (based on the novel by Joyce Maynard, who also wrote the source book for Gus Van Sant's To Die For). And make no mistake, that's drama read "melodrama", as in Douglas Sirk-ian 1950s level yarns, so unapologetically awash in far-fetched dysfunction and hot-house volatility amid gloriously stretched-thin plausibility. Such is the melodramatic intent and vibe of director Jason Reitman's new uncharacteristic film. (Reitman being the maker of snarky stylish comedies of the now, always about troubled individuals, such as Juno and Up in the Air.)

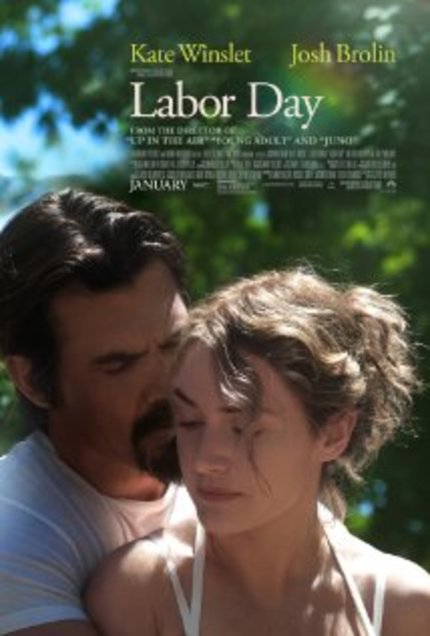

Much of the attention focused upon Labor Day has been about how absurd and/or foolish it is. And by "it", I mean the characters, as played by Kate Winslet, Josh Brolin, and Gattlin Griffith. They say, do, and allow the kinds of things that above-it-all audience members live to criticize: Who'd voluntarily drive an assertive stranger back to their home just because he insists it "has to happen"? Who'd allow themselves to fall in love with said strange man who's clearly considered dangerous?? And upon the lady of the house eventually falling for this manhunt target, why wouldn't they bother to come up with a cover story to appease the myriad of neighbors and law enforcement who come a-knocking???

It's 1987 in a sleepy east coast community. Brolin plays Frank, an escaped convict who was in prison for murder. When he meets up with single mom Adele (Winslet) and her adolescent boy Henry (Griffith) in their small town department store, he somehow finagles his way back to their home, taking up refuge there while the cops, community and media hunt him down. The accusations of absurdity come with the fact that in the world of the film, this is all a good thing: Frank turns out to be a great guy to have around, and the testosterone-radiating cure to what's ailing soul-damaged divorcee Adele. Lonely-heart Adele and Henry sooner than later come around to not minding occasionally being tied to chairs, playing the part of prisoners, every time someone knocks at the door. After all, Frank means well - if he were to be caught in the house, he couldn't bear the thought of this mother and son being charged with sheltering a known criminal. If they can simply keep up appearances (a vital part of so many classic melodramas), it means Frank can stay longer, and continue doing his handyman hoodoo all over the home and car.

But of course times have changed in terms of the way audiences and even critics accept such melodramatic tropes. Hence, Labor Day is already infamous in critical circles as the new audience-interactive mockable movie sensation of the decade, with filmgoers encouraged to show up with their buddies ready to verbally mock it ala some sort of "Mystery Science Theater 3000" for romance novel-derived movies.

While such a thing could be fun to a point, it'll never take. If any such would-be hecklers were to get deep enough into Labor Day, I doubt they'd find a lot what awaits them to be hilarious comic fodder. That said, the pot-boiled reality of it all does evoke a certain disconnect from the way we live now. It's self-serious, hot and bothered weepie-sadness on a stick; the kind of "other peoples trouble" escapism that may appeal more to middle aged women than anyone else. It might just be the Fast & Furious of two-hankie weepies.

And I bought it. I bought almost every minute of it. I may be the wrong gender in the wrong decade in the wrong region, but I honestly bought all up. I liked that Brolin's character is resourceful enough to know when to tie up his hosts, and careful enough not to blab that in his heart of hearts he didn't want to do it, as it would only placate them. They would figure out the deal soon enough anyhow.

I liked how Winslet is a Real Woman, and I liked how Brolin is a Real Man. Not undamaged, not untroubled, not without hopes. But real in that base estrogen feminine/testosterone sweaty kinda way. If nothing else, this is exceptional casting, as these qualities of old school "authentic" are lost on so many contemporary movie stars. Word is Reitman waited to make Labor Day for years until Winslet was available. Smart move. As for Brolin, it's honestly too bad he's had so much trouble landing in a hit. Labor Day likely won't help that, but hopefully he'll escape his rut, as his unique presence is appreciated in even his overall least effective films.

Finally, I liked how the movie stopped for a good few minutes for Brolin to teach them how to bake a peach pie the old school way. For whatever reason, I shared the fascination the camera maintains for this sequence of utter process - hands kneading and pounding out dough with lingering exactitude and precision that other films reserve for handguns and sports cars. Then, the pie bakes the in the oven in an uncool time lapse shot. I don't even like peach pie very much, but man, did I like the saccharine curveball of this out of left field sequence.

Jason Reitman, in attempting to resurrect the "women's film" of yore, has managed to cook up a rare thing at the movies today - individuals in a precarious situation too human to read as out-and-out movie characters, yet too characterly to strike viewers as entirely real. This is the stuff of Douglas Sirk and his earlier contemporaries when they set out so long ago to entertain the masses with such compelling strains of melodrama. (And yet, Labor Day finds time to be a coming of age film for young Henry, as well.) Labor Day isn't merely like a film from another time, it's from a different medium, out of place. Thus, it's somehow fitting that Labor Day isn't opening anywhere near Labor Day. Reitman is parlaying his success to force this film upon us the way Brolin's Frank forces himself upon Adele and Henry; it's up to us to fall for it or not. This movie simply doesn't belong anywhere these days. And sometimes, that's a good thing.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.