Full Disclosure: ScreenAnarchy's Lists of Shame - April (Part 2)

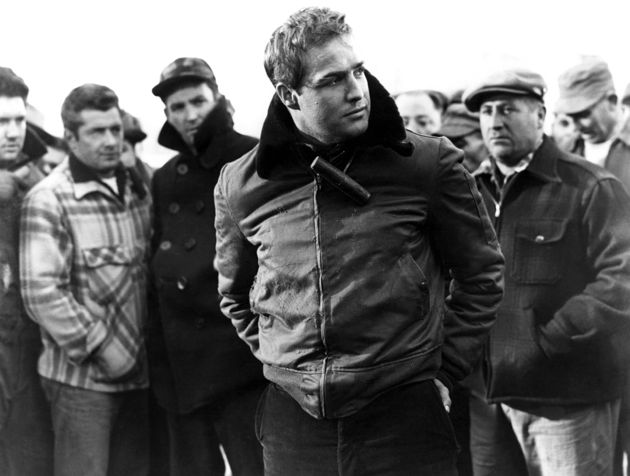

On the Waterfront (dir. Elia Kazan, 1954 USA)

Winner of 8 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Screenplay, winner of 4 Golden Globes, including Best Picture - Drama and Best Actor - Drama

J Hurtado, Contributing Writer:

All I knew about Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront going in was that it was the source of the "I coulda been a contender" speech that Jake La Motta performs in Raging Bull. I knew that Marlon Brando played a former boxer, and that he had fallen from grace for one reason or another. What I was not prepared for was the gut-punch I got from a story so typical of '50s cinematic rebels. The dismantling of the American Dream and disintegration of the perfect American family are key elements in making this film one that transcends its component parts and becomes a timeless epic of defeat and redemption.

While the impossibly rugged and handsome Marlon Brando and his unusual method approach to acting is certainly the most talked about element of the performances in the film, it's far from the only reason the film is noteworthy. Yes, Brando turns in an emotionally draining and physically aggressive performance for the ages as longshoreman Terry Malloy, but without a solid cast to bounce off, it would have been a hurricane in a vacuum. I was pleased to see so many seasoned character actors: Karl Malden as Malloy's moral center, Father Barry; Rod Steiger as Malloy's conflicted sacrificial lamb of an older brother, and Lee J. Cobb in an iconic performance as union kingpin, Johnny Friendly. All of these actors are incredibly strong and make for one hell of an ensemble. Even Eva Marie Saint acquits herself nicely as the damsel in distress.

Ultimately, however, it was the story that had me hooked. I come from a union family, it's in my blood, and to watch this most sacred trust among comrades defiled by organized crime is deeply upsetting. Of course, this was the whole point. Unions weren't yet long in the tooth, having only emerged as a major force about 50 years before On the Waterfront, but it was very quickly found by organized crime that this union atmosphere was a perfect way to control entire trades without having to do it one man at a time. To this day it saddens me to see some unions struggle under the choke-holds of special interests that don't represent the majority of members. Writer Budd Schulberg understood this and wrote a screenplay that is just as prescient today as it was 60 years ago.

I wasn't prepared for the range of emotions through which On the Waterfront would wring me, but I'll be damned if I wasn't a blubbering wreck by the end. Between Brando's picture perfect characterization of a man on the brink of collapse, and visualization of the damage that can be done when good men do nothing to stop it, I was done for. On the Waterfront is probably the most affecting of my List of Shame films yet, and we're only 4 months in. God help me.

2001: A Space Odyssey (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1968 USA)

Winner of the Academy Awards for Best Visual Effects, winner of 3 BAFTAs, including Best Cinematography and Best Art Direction

James Dennis, Contributing Writer:

I went on my space odyssey with little baggage, or as little as you can have when watching such a canonical film. Of course I knew its reputation as a seminal work of sci-fi Cinema, but precious little about its plot or structure, save for the inclusion of some computer called HAL. It's safe to say I've probably avoided, or at least put off, watching it until now. I've never been a particular fan of sci-fi movies - I don't even like Star Wars. And the ones I do like tend to be grounded in a reality of sorts or are actually horror flicks, with Alien and The Thing springing to mind. Stanley Kubrick on the other hand, I do have a lot of time for. A Clockwork Orange and The Shining are favourites, so I was instantly at home with the familiar Kubrick-isms in 2001: A Space Odyssey (though of course it pre-dates both) when I finally settled in to indulge it.

The apes. I wasn't ready for the apes. I'm not sure what I was expecting, but I think it was a film about a 60s spaceman and a smug computer. Cynical is usually my default mode, but such is the scope, grandeur, audacity and beauty of 2001 that I was completely won over. Even before the unexpected ape action. That credit sequence to Richard Strauss 'Sunrise' fanfare is spine-tingling in a rare, all-encompassing way.

After that I quickly lost count of how often I made internal recognition grunts at aspects plundered for subsequent sci-fi movies or pop culture fodder. The influence of Kubrick's metaphysical wonder is staggering; 'iconic' doesn't even scratch the surface. Also astounding is just how timeless 2001 is. I thought it might be a very 60s vision of space, that would be horribly dated and easy to mock, but far from it. Not once did I find myself distracted by any impingement from ghosts of filmmaking past. Of course some of the space paraphernalia now looks a little less than what we'd expect from a modern sci-fi picture, but I simply took it as a different vision of space, not a dated one. Frighteningly, some of the technology appears to be remarkably current - I swear I saw an iPad in there at one point. And the effects are absolutely flawless, and tangible, to this day. Take that, CGI.

I'm somewhat taken aback by how much I liked this film. Its imagery and soundscape stayed with me for days afterwards, much like Orange and The Shining did, and I'm not sure Kubrick's famously meticulous nature has ever been so clearly marked on screen.

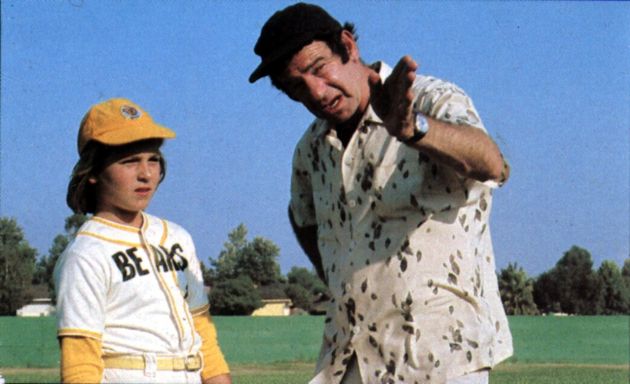

The Bad News Bears (dir. Michael Ritchie, 1976 USA)

Winner of the WGA Award for Best Comedy Written for the Screen, nominated for the BAFTA for Best Actor

Jason Gorber, Contributing Writer:

Way back in the Yearrrr Two-Thousandddd (cue Conan-style music) I interviewed this charming young punk named David Gordon Green, talking about a film he'd just made called George Washington. He looked younger even than his 25 years, admitted to me that he carried a photo of Terrence Malick in his wallet (I wonder if he still does that?), and told me his favourite film was The Bad News Bears. I told him I'd never seen it, and he looked incredulous. He said I had to see it.

It took me thirteen years.

Knowing how much DGG loved this baseball film, it made the decision to work with Danny McBride, Jody Hill et al on a ribald project called Eastbound & Down, featuring a delightfully inappropriate lead character easier to understand. What comes across strongest when watching a boozing, swearing, surly Walter Matthau scowl his way through much of Bears' running time, is that they'd never have the (base)balls to make a film like this again.

When a major plot point is a father beating the crap out of his kid on the mound, or when one of the precocious whippersnappers talks affectionately about the "Jews, Spics and Niggers" that make up their team, you know this isn't a made-in-committee kids flick that we've grown accustomed to.

It must have been revelatory seeing The Bad News Bears at the time, but I do wonder how much of the darkness was just taken as silly comedy. Matthau was nominated for a BAFTA for his performance, and the script won the WGA Award for best script, beating out the likes of Neil Simon, so you'd think that somebody must have noticed there was more going on here than just a stupid kids movie.

I can't say these decades later that it's a particularly entertaining film. The story points are telegraphed well in advance, the shock value from precociousness no longer having the same zing. Still, it's undeniable that Matthau is near perfect in the film, and the performances that Michael Ritchie gets from his ensemble of brats is commendable.

I think a direct line can be drawn between Bears and the likes of Bad Santa. Yet while the baseball film has a certain sense of anti-heroic joie de vivre, Bad Santa is simply melancholic dreariness with a pat ending, trading on snark as the core of what's meant to be enjoyable.

I'd like them to make kids movies as shocking and inappropriate as The Bad News Bears again, while remembering that the goal is also to have some sort of story structure and entertaining, not entirely predictable, story line. Again I would have to point to Eastbound as a project that gets this tonality right, a rich, varied storyline, shifting between completely unpredictable to comically obvious story beats.

While we can't credit DGG with the entirety of Eastbound's success, it's easier now to see the Bad News Bears DNA that's carried throughout. And that, I would argue, is a pretty phenomenal legacy to have.

Gattaca (Dir. Andrew Niccol, 1997 USA)

Winner of Best Film at Sitges International Film Festival, nominated for the Academy Award for Best Art Direction, nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Original Score

Jim Tudor, Contributing Writer:

I remember when Gattaca came out in 1997, it wasn't a big deal. Sure, it was a futuristic movie with rockets blasting off and identity intrigue and Uma Thurman (still hot from Pulp Fiction), but my memory is that critics shrugged, saying things like, "If you're interested in genetic tinkering, skin flakes, and urine samples, then this is the film for you!" Notices like that did nothing to motivate me. Back then I was a busy college student of limited resources. If I was going to see a movie in the theater, it was gong to be the Special Edition re-release of Star Wars for the eighth time! Sorry, Gattaca - you may've been the boisterous new smart kid on the block, but back then you couldn't compete with George Lucas' promise of "A few new surprises."

As I got older, a strange thing kept happening. People would not stop asking me if I'd ever seen Gattaca. (I know - weird!) The movie absolutely would not go away. As I try to remember who exactly these assorted Gattaca devotees were, I can only surmise that they were mostly seminarians, and were approaching me at church. It seems that the local seminary may very well have this film on a permanent loop, forever fostering intense discussions and observations about the ethics of genetically engineered favoritism, and how it's all more relevant now than it was then. Goodness knows their interest was certainly piqued, and I was getting the idea that I might be missing out on some decent chats about this film. So why not take this opportunity to nix Gattaca from my own cinematic List of Shame?

I guess this is the point where I'm expected to say how glad I am to have finally seen Gattaca, and how all those fans that kept seeking me out were right, and how it's a gleaming futuristic treasure for the ages. But the truth is that it did virtually nothing for me. Perhaps (despite the 1997 notices about urine samples) it had become too built-up in my mind. Maybe a part of me never wanted to like it, and resented being made to watch it. I don't know. It's not a poor film by any stretch. It's got a solid look, a competent direction from then-newcomer Andrew Niccol, and yes, ideas that are more relevant now than they were then, blah blah blah. But it still just kinda sat there.

Frankly, I was surprised to see Gattaca among the 200 or so films on the ScreenAnarchy master list for this exercise. For many non-seminarians, the legacy of Gattaca, more so than anything else, is the failed Hollywood marriage of its stars Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman. I'm sorry for them, and the fans, as that pretty much ensures they'll never be game for a sequel. But for me, I'm okay with that. There was no shame in having not seen Gattaca. (Now where's that Star Wars blu-ray...?)

Kwenton Bellette, Contributing Writer:

I suppose this one becomes a shameful watch because it was a highly prolific film; a very accessible and entertaining sci-fi with a lot of inherent symbolism, rife for high school dissection. Well my school chose The Truman Show at the time, I'm guessing because the serious-looking besuited people on the VHS cover weren't exactly appealing to my teenage eyes. But I digress.

Should Gattaca really be a shame movie? It is really good and a solid, if uncomplicated and undemanding sci-fi, it is well acted across the board and the pacing is nearly perfect. Do people really gasp when I declare I have not seen it though? I think not.

What I found so great about Gattaca was its film noir elements, which it wears proudly on its chest. Instead of embracing the absolute future, this 1997 production becomes something indelible due to its warped genre perspective, a fresh idea even today, and not nearly as well-implemented as in other sci-fi mash-ups since then. Comparatively, Gattaca is Niccol's best film ever, especially if his turgid trajectory of mediocre sci-fi continues.

Come and See (dir. Elem Klimov, 1985 USSR)

Winner of the Golden Prize and FIPRESCI Prize at the Moscow International Film Festival

Kurt Halfyard, Contributing Writer:

If there is a film deserving of its reputation, it is Elem Klimov's devastating Come And See. One of the great anti-war films, which plays somewhere in the no-man's-land between surrealist horror film and gut-wrenching passion play. And yet the film is hauntingly beautiful, particularly in the first act. I feel as if I can breathe in the scent of Belarussian pines. I feel as lost in the fog and the bog as young Florya, who cannot come to grips with the fact that his mother and sisters are dead mere days after he is (voluntarily) scooped up by Russia's guerrilla Patriot forces. I feel a dampness in my bones that will never leave.

The latter half of the film feels as if it was inspired by Carl Theodore Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc, as we see young Florya prematurely age (and become rather androgynous in the process. He (and we) bear silent witness to atrocities of German soldiers on the Russian peasants the likes of which have never been captured this strongly on film; not in Roman Polanski's The Pianist, not in Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List. Lost in the fog, living in a pure hellish apocalypse where society is a grotesque gargoyle-faced mockery of itself.

I imagine that this film was a huge inspiration on Michael Haneke's severely underrated Time of the Wolf, which seems to borrow key images of a burning barn, dead cows and horses in an open and barren countryside, and a grey clothed, blood crusted-lipped boy stumbling through barely penetrable fog. But Klimov's film has a significantly greater impact because it wants you to feel the very horror of war right down to the last pair of eyes looking out from the filth and carnage. Breaking one of those unwritten rules of filmmaking, the director often has his actors look directly into the camera, directly into your soul. When Florya starts shooting his rifle at the camera (another taboo) in an attempt to reverse history, the director makes this literally happen on screen. But it is a temporary fantasy, as the survivors have to march onward in the damp woods. Also, if there is a case for why 35mm film looks better than digital, the cinematography of this film is indeed it.

Never, I repeat, never, watch this film as a double bill with Isao Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies. I agree with Phil de Semlyen when he described Come and See as, "The worst date movie ever." Nevertheless, the experience of viewing this Russian masterpiece alone and in the dark will not leave me any time soon.

Peter Gutierrez, Contributing Writer:

Because I've spent so much time writing about horror movies over the years, acquaintances often remark (their disdain barely repressed) "Hmmm, well how can you stand watching such horrible brutality all the time?" My pat answer is that horror has never been the most disturbing genre for me - that would be war movies, because they typically depict cruelties and barbarisms that you know could very well have taken place... or actually might be taking place right now in some corner of the globe.

In fact, here's an unlikely parallel that nonetheless makes perfect sense to me: I recently saw Frankenstein's Army, about Soviet troops who encounter unspeakably hellish nightmares as they trek through Nazi Germany. It doesn't compare to Come and See, which is about Soviet forces and ordinary people trying to deal with the unspeakably hellish nightmare that the Nazis (and the war generally) have made of life itself in the Belarussian countryside. Now, I say that having liked Frankenstein's Army a great deal, but in terms of sheer sustained horror that makes you see and feel things that will stay with you forever, there's simply no contest.

Of course there's tremendous artistry to Elem Klimov's film as well - the compositions in depth, the breathless handheld tracking shots, the tremendous use of sound to create subjective states (mostly madness) - yet early on it becomes clear that story is everything here. Yes, Come and See is a prime example of substance over style, but the fact that the style itself is so masterful indicates how powerful that substance is. The choice of a youthful protagonist who is initially overflowing with both nationalism and idealism as he signs on to fight for the homeland is of course reminiscent of All Quiet on the Western Front. The difference here is that our point-of-view character is considerably younger, and that the horrors he encounters do not take place in frontline trenches but as he staggers through a hideously transfigured rural landscape, separated both from the army he has joined and, increasingly, from a world that makes any sense at all.

The result is a twisted picaresque that provides the shocks and absurdism, which are equally heartfelt by the way, of something like Jerzy Kosinski's The Painted Bird. Also, in its death-saturated sensibility (you'll never forget the skull on a stick that wears a German uniform) and its ethereally episodic structure, Come and See for some reason reminds me of Jodorowsky's El Topo. Oh, and I guess if you had to fuse those two texts and situate it in a war movie generically you might have Apocalypse Now. However, terming this an "anti-war film" kind of short changes what Klimov achieves here - by the end of Come and See you'll be despairing of humanity, not just warfare.

Pierce Conran, Contributing Writer:

Shamefully (this is the list of shame feature after all) I missed my turn last month, as I was supposed to watch Tarkovsky's Solaris. This month my entry is also a Soviet film, the harrowing World War II film Come and See (1985). Like the other films on my list I had always meant to watch this and there was no particular reason for not having seen it. I love war films and this one has a stellar reputation but I guess I wasn't sure what made this one stand out. To learn that, I needed to see it for myself.

Many war films are devastating portrayals of the horrors that occur during wartime. Examples such as Schindler's List and Night and Day are some of the most well known but I'm not sure I've ever witnessed something quite so harrowing as Come and See. Set in the earthy Belarussian countryside, the film drags us around with its young protagonists through eerie tracking shots, a technique rarely used to such terrifying effect outside of Kubrick's films. Though things are bad to begin with, the ominous atmosphere sets the stage for a chilling event that happens later on.

The film's surreal and shocking climax is not something I'll easily forget. 628 villages were burned to the ground and scores of woman and children murdered by Nazi soldiers in Belarus. Come and See gives us a front row seat to one such massacre for its climax. More psychologically terrifying than graphic and all the more effective because of it, this is truly the stuff of nightmares.

Stagecoach (dir. John Ford, 1939 USA)

Winner of 2 Academy Awards, including Best Supporting Actor and Best Original Score

Shelagh M. Rowan-Legg, Contributing Writer:

By a lucky coincidence, Stagecoach was one of the selected films for the Film Contexts course on which I was a teaching assistant this year. The class watched it in conjunction with a discussion on authorship/auteur theory (the week previous we had watched The Searchers, in conjunction with genre theory). I've never been a huge fan of older, more traditional Westerns. There are usually so few female characters, and what there are are pretty underdeveloped. I also never had the romantic view of the Old West that so many seem to. That being said, I'm loving a lot of the current neo-westerns like Blackthorn and Meek's Cutoff, so I was interested to go back to the genre's origins.

John Ford has long been synomymous with the Western, and it's not hard to see why, given that Stagecoach has everything that one expects in a Western: cowboys, Indians, Mexicans, settlers, a drunk doctor, a prostitute, a guy on the lam. The familiar themes are there, and Ford sets them up in perfect concert with the Hollywood classical style: the garden versus the wilderness, the savage vs the civilized man, East Vs. West. The comparison between it and The Searchers among my students was very interesting; there was definitely a preference for the latter, as its politics are slightly more progressive. This isn't to say that they didn't like Stagecoach. This was the film that put John Wayne on the star map, and from then on, despite some variety of roles, he would always be known as a cowboy.

For my part, though, I can't say that I enjoyed it. I appreciate why it is considered a classic, and I can see Ford trying to put his own signature on the films, particularly in the scenes between Wayne's Ringo, the guy on the lam seeking revenge for his murdered brothers, and Dallas, the prostitute with a heart of gold who seeks redemption and forgiveness. Instead of the standard shot-reverse shot, Ford instead frequently shot them side by side, talking to each other both in the frame, as though to emphasise their equality. But overall, I found it pretty dull and predictable, certainly from a narrative perspective and in many ways from an aesthetic one as well. This is Hollywood classical film, which follows a formula. There are other Ford films that I enjoy (such as The Searchers, Young Mr Lincoln and Rio Grande). Perhaps this was not so much about Ford, but my dislike to early Westerns and their formula.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.