Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975 USA)

Winner of 3 Academy Awards, including Best Editing, Best Original Score and Best Sound, the BAFTA for Best Film Music and the Golden Globe for Best Score

Todd Brown, Founder & Editor:

So, here's the thing. There's a very particular reason why I had never seen Jaws before now. My uncle was an accident baby, born to my grandparents long after any of his sisters, my mother included. He was just a couple years older than my oldest cousin and functioned far more as a peer to the lot of us than to my aunts. He was responsible for my very first cinematic experience (Superman) and when he was around twelve or thirteen he showed Jaws to my older sister, who would've been eight or nine at the time. She was so terrified that she was afraid of using the toilet for the next several weeks, lest a shark come up through the water and bite her on the bum. Which ruled it out for me at the time, of course, and I was never able to shake the association with a fear of toilets which made seeking it out in later years seem rather silly.

But here's the thing. They never really made 'em like this before Jaws and they don't make 'em like this any more, either. The most remarkable thing about it is not the shark effects – which are quite effective – but how few of them there actually are. Jaws is far more a character piece with the key residents of a small town coping with the presence of the shark than it is the sort of exploitive fare that'd be made of this story today. Hell, you don't actually see the thing until you're half way through! But the acting is fabulous and the storytelling stands up one hundred percent. Fabulous entertainment.

Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975 USA)

Winner of 3 Academy Awards, including Best Editing, Best Original Score and Best Sound, the BAFTA for Best Film Music and the Golden Globe for Best Score

Eric Ortiz Garcia, Contributing Writer:

I became Todd’s "Jaws buddy” when confessing to the ScreenAnarchy gang the cultural gap I had with this Spielberg classic. As I was (finally) watching Jaws I realized some of its scenes, as well as the tone, weren’t unfamiliar to me. This means I had seen plenty of The Simpsons (the blackboard scene and the shark prank came to mind) and some other Spielberg films.

Jaws is an influential film with two different parts. The first one is amazingly entertaining, with Spielberg shaping Scheider's worried police chief into a protagonist we care for. Memorable characters are introduced (a rich kid and a crazy old man, both shark experts), obscure moments appear, as well as a political thing: there’s a killer shark but the 4th of July celebration is near so the beach must remain open for business.

The second half is a straight “going fishing” thing, it may be overlong but there’s good ol’ male camaraderie and, obviously, the giant killer. My favorite scene without the shark (during this fishing trip) has Shaw and Dreyfuss showing off their battle scars, putting Scheider to shame. It’s absolute fun!

I found simple yet very effective storytelling during the entire movie, much like in Jurassic Park, where every little thing is there for a good reason. It’s quintessential Spielberg, with a classic score too. John Williams delivers a sinister sound but also a “heroic” one, echoing his later work in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Jaws was overall a highly satisfying experience. Scary? Tense? Not quite for me. I now admire it for other reasons, as a daring blockbuster with severed legs and intestines that also manages to offer almost-improvised interactions between its stars. The shark may not scare you but it sure makes ‘em bleed!

Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975 USA)

Winner of 3 Academy Awards, including Best Editing, Best Original Score and Best Sound, the BAFTA for Best Film Music and the Golden Globe for Best Score

Stuart Muller, Contributing Writer:

I had almost seen Jaws. When I was 7, my eyes still twinkling with naiveté, I went to my friend’s birthday party and watched the opening scene. Today, a quarter century later, I can still feel us all sitting there, cramped together on the carpet in his lounge, the curtains drawn to dim an already gloomy room, excited and excitable as only a bevy of boys can be. I remember this so vividly right now because, last night, I was unexpectedly hurled back into the horrified psyche of my 7-year mind witnessing its own innocence being torn limb from screaming gurgling limb in the darkness and the water. PfuckingG??? I also recall the brouhaha between his mother, herself now personally traumatized and parentally mortified, and a frenzy of sugared-up sharked-up kids who’d just tasted their first forbidden blood. Not me though! I almost cheered when she pulled the plug.

There was no saviour mother last night though. Just my smug, knowing, sonofabitch-ofa-housemate who watches Jaws every 4th of July. It was the end of a long day’s good company, soaked in salubrious debauchery (Happy Birthday USA!), so we retired to Amityville. “Amity, as you know, means ‘friendship’.”

For various reasons, older classics often don’t live up to their hype on first viewing. But then there are some… some blow everything else so far out the water that the heavens rain glorious buckets of blood and guts and mangled sharkmeat! Gods, what a magnificent movie! Spielberg is clearly captaining this film on another level; it’s just dripping creativity and craftsmanship, and his leadership seemingly brought the best out of everyone involved.

Thank you Jaws. I now, perhaps for the first time, truly grasp why Spielberg is so revered. Also, I cannot fucking wait for Sharknado!

A Clockwork Orange (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1971 UK/US)

Nominated for 4 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, Winner of Best Foreign Film at the Venice Film Festival

Peter Martin, Managing Editor:

While I have great affinity for Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut, Stanley Kubrick's other works hold much less personal interest for me. I've seen some of them and hold them in varying degrees of regard, but more as objects of admiration that I have revisited only occasionally. With its strong intimations of a juvenile sense of humor and sickening glorification of violence, A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick's notorious 1971 adaptation of Anthony Burgess' 1962 novel, has always fallen rather low on my "want to see" list.

My instincts for avoiding the movie were dead-on. It's distasteful in its refusal to express a point of view, even though it occasionally features voice-over narration by Malcolm McDowell as youthful offender Alex. It introduces important issues (violence, sexuality, criminality, free will, redemption) and leaves them largely unexplored in any depth. It feels incredibly scattershot in its approach, and I was completely underwhelmed, though not as shocked as I once might have been, and in no way offended.

As far as admiration is concerned, the film definitely feels like a followup to 2001 in its art direction and mixture of past, present, and future in its production design, costuming, and makeup, and I can see how certain scenes in Full Metal Jacket are corollaries to the prison scenes here. Also, it was a pleasant surprise to see Philip Stone as Alex's father, more than a decade before his turn as Grady in The Shining.

Schindler's List (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1993 USA)

Winner of 7 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction, Best Editing, and Best Original Score, 7 BAFTAs including Best Film, 3 Golden Globes and numerous other awards.

Ryland Aldrich, Festivals Editor:

Without a doubt the film I've most dreaded from my list of shame is Spielberg's tear-jerking masterpiece that cleaned up pretty much every award given to the films of 1993. I blame the origins of this avoidance on my 8th grade Holocaust curriculum I completed just the year before the film came out. To say I had gotten the point at the time of my tender upbringing would be an understatement of Elie Weisel proportions. But just as my initial reluctance to tour the death camps of Auschwitz when I visited Poland the better part of a decade ago proved baseless, the results of finally sitting down and watching Schindler's List were much more rewarding than my long-gestating hesitation had steeled me for. Yes, this is a great movie -- and no, it is not as emotionally exhausting as an 8th grade Holocaust lesson plan.

I was surprised right out of the gates at the level of stylization Spielberg employs to make the film feel of its time. The choice to shoot in black and white is obvious but the camera angles, editing, and direction of the first act are all nods to the great films of the 1930s and 1940s. This dissipates as the story kicks in and from that point the film impresses most on the strength of the performances by big Liam Neeson and, perhaps even more importantly, the supporting roles by Ben Kingsley (not yet a knight back then) and Ralph Fiennes (this being breakthrough role before we learned not to pronounce the "L"). Yes the film ventures a bit too far into emotional sentimentality but what Spielberg film doesn't. But all things considered he shows restraint in his use of heart-string-yanks and manages to tell a very engaging story out of some extremely delicate subject matter. All of this makes the film well worth the watch and a rewarding revisit from a filmmaking perspective as well if you haven't seen it since you were forced to sit through it in school.

Schindler's List (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1993 USA)

Winner of 7 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction, Best Editing, and Best Original Score, 7 BAFTAs including Best Film, 3 Golden Globes and numerous other awards.

Brian Clark, European Editor:

I didn't avoid Schindler's List because I thought it wouldn't be good, but rather because I didn't see how it could possibly surprise me. I know Spielberg is an expert at manipulating emotions and also that the Holocaust was horrible on a number of different levels, not just the obvious genocide part.

But Schindler's List was bolder and more well-directed than I had been led to believe. The first hour, especially, is some of the finest visual storytelling of Spielberg's career, and surprisingly off-kilter in its pacing. Also, rather than simply wallowing in the visceral tragedy (although there's plenty of that), I appreciated the way Spielberg emphasized the bureaucratic and mundane elements of the Nazi strategy, the desks laid out to issue papers which would eventually be invalidated anyway, which actually make the whole thing seem even more cruel, and unfortunately, relevant.

I enjoyed watching Neeson as Schindler and raise no disputes here that the man's story deserved to be told. Yet, I never fully connected or even totally empathized with him. Perhaps when Spielberg's images push the audience so strongly to put themselves in the place of the victims, the moral courage of a rich business man who ultimately makes the right choice pales a bit in comparison. Still, Neeson acts the hell out of his final scene, and despite a few moments which feel a bit too telegraphed and manipulative (the subplot with the maid especially), Spielberg earns all of the grief and reflection that the film evokes.

Red Beard (dir. Kurosawa Akira, 1965 Japan)

Winner of the Volpi Cup for Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival

James Marsh, Asian Editor:

Having owned Red Beard on DVD for close to 10 years, this seemed the perfect opportunity to finally crack it open and experience one of the few Kurosawa films I had yet to see. Perhaps the prospect of a 3-hour medical drama had deterred me until now, but it shouldn't have done as Red Beard is, in my opinion, one of the director's very best.

The story focuses on a young trainee doctor (Kayama Yuzo) who must ride out the last stage of his training at the side of Mifune Toshiro's "Red Beard" - a seemingly gruff, but ultimately humane and heroic surgeon, who services an impoverished district of Edo. As the hotheaded apprentice hones his craft and learns the importance his role has on the community, the film takes its time to explore the various backstories of many of their patients.

While the story may be small in scale, the production was huge, boasting authentically built sets and an exhausting two-year production schedule. Red Beard proved the last collaboration between Mifune and Kurosawa, but should not be dismissed for its lack of swordplay or nourish thrills. Red Beard is every bit as heartbreaking and beautiful as Ikiru, gorgeously photographed and incredibly well acted. Mifune, whose role is really in support of Kayama's emotional journey, even gets the chance to show off his fighting skills, when he is forced to fend off a gang of thugs who run the local brothel. All in all, this has been a wonderful discovery that should have happened many years ago.

East of Eden (dir. Elia Kazan, 1955 USA)

Winner of the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, Winner of Best Dramatic Film at the Cannes Film Festival

Jason Gorber, Featured Critic:

Based on a novel by John Steinbeck, featuring the first starring role from iconic talent James Dean, and a promise of a colourful, Cinemascope epic from Elia Kazan, 1955’s East of Eden seemed a surefire work to add to any list of shame.

Having recently revisited On The Waterfront, the film that immediately preceded Eden in Kazan’s filmography, I was struck by how much the neo-realist noir succeeds as a taught masterpiece, even if the messianic ending leaves a little to be desired. Iconic scenes with Brando, Cobb and Steiger are riveting, the compositions by Boris Kaufman engaging, the script by Schulberg taught and uplifting.

One year later, Kazan traded gritty East Coast ports for the resplendent lands of California. Lush scenery is shot in super widescreen by Ted McCord, the edges of the frame mildly distorted with the wide angled lenses. Tilted, “Dutch” angles are meant to be provocative yet become nausea inducing. These flourishes undermine further the relatively banal story Kazan is trying to tell. While the production design works well, particularly in the outdoor scenes, the camerawork distracts throughout.

As for Dean’s starmaking performance, my immediate reaction was to see it as farcical mimicry of Brando’s mannerisms from Kazan’s earlier film. The 1955 New York Times review put it better than I ever could, calling the lead “a mass of histrionic gingerbread.”

Steinbeck’s narrative is heavy-handed to the point of pedantry, the Cain/Abel metaphor given a kind of saccharine, shallow happy ending. Only Oscar winner Jo Van Fleet as the matriarch seems up to the task, with plaudits for the affable Burl Ives and Albert Dekker in their character parts.

I’m not sure I need to visit East of Eden again, for the tedium almost led me to the land of Nod.

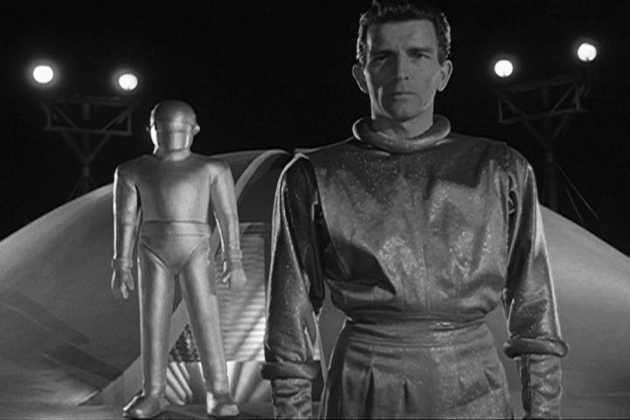

The Day The Earth Stood Still (dir. Robert Wise, 1951 USA)

Winner of the Golden Globe for Best Film Promoting International Understanding

Andrew Mack, Contributing Writer:

Klaatu does a really shit job of staying 'not shot'. For all the technical advancements his race has made - interstellar space travel and taller-than-your-average-man robots with frickin' laser beams coming out of their heads - he is pretty bad at staying alive. I get the Alien Messiah analogy but if my upbringing in the Church has me thinking that something else would probably be more representative, then I say this is more akin to Missionaries who go deep into the jungles and get slaughtered by the natives. You have all the tools to get you deep into the dense forest but it's the simple savage's pointed stick that gets you in the end.

Otherwise this movie has all your favourite tropes from classic sci-fi. I especially love some of those practical effects in the ship like the shadow of the back-lit spinning desk fan against the main screen. That is do-it-yourself magic right there folks! And there is no denying the power of the theramin either. I fell under it's trance and woke up strangling my houseguest yelling Klaatu! Barada! Necktie! Necturn! Nickel!

Klaatu's final speech kind of threw me off though, 'Shape up or these robots will go crazy and kill your asses'. What the heck, man? No, 'Here is how we can help'. Just, 'If your shenanigans spill out onto the intergalactic street we're calling the cops'. For an advanced society this certainly is not a healthy way of dealing with the riff raff. Mind you, if I got shot a couple times I would be pretty pissed too. At myself. And embarrassed. Note to self: If you're going to show off the wonders of the universe, never bring it in a spring loaded sharp thingy. Earthlings be twitchy.

The Long Good Friday (dir. John MacKenzie, 1980 UK)

Nominated for the BAFTA award for Best Actor

Ard Vijn, Contributing Writer:

John MacKenzie's 1980 London mob thriller The Long Good Friday is a bit of an odd one out on my list. The film is neither considered a certified classic, nor comes from a particularly famous director. Its attraction to me was based mainly on vague recollections of critics praising the actors. And the premise of someone literally undermining a powerful criminal syndicate intrigued me.

Well, consider this one of my happy surprises as the film is excellent. The Long Good Friday has dated in all the best ways, meaning it's obviously taking place in a certain era rather than obviously being made in one. Apart from its score perhaps, which isn't bad, but could have come from an Italian zombie flick.

Bob Hoskins is fantastic as a bullying mob boss who sees his empire attacked, and so is Helen Mirren as the woman who can get him back on track whenever he goes berserk. Plenty of fun can be had by recognizing supporting actors, especially an incredibly young Pierce Brosnan. And even if the outcome of the story didn't surprise me much (as there are only so many ways such a tale can end), the road towards the final shot had some pretty good surprises in it.

While the film is certainly not as flashy as the more recent Guy Ritchie “mobbedies”, there are plenty of interesting flourishes which show that director John MacKenzie was quite a talent indeed. It is interesting to see that IMDB shows a remake is in the works. Unless they seriously change the era, the outcome of the story, and the villain, I cannot see how anyone could possibly succeed in making a better film.

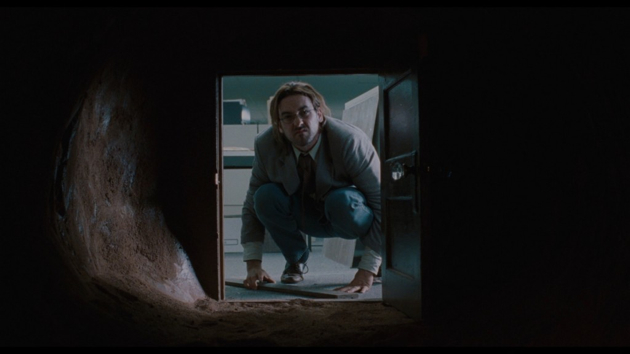

Being John Malkovich(dir. Spike Jonze, 1999 USA)

Winner of the FIPRESCI prize at the Venice Film Festival, nominated for 3 Academy Awards, including Best Director and Best Original Screenplay

Christopher O'Keeffe, Contributing Writer:

Being John Malkovich always seemed like one of those movies that a friend would catch on TV late at night and then rave about the next day. The title alone makes it stand out and the plot, a man finds a doorway that leads into the head of actor John Malkovich, is not easily forgotten. One of the great things about finally seeing a film you've heard so much about for so long is realising how it completely defies expectations of what you thought it would be, and this movie has so many wonderfully unexpected details and quirks.

Directed by Spike Jonze and written by Charlie Kaufman, this was the first feature-length film for both men and while Jonze was, and perhaps still is, best known for his clever music videos, this is where Kaufman made his name. It's not hard to see why Kaufman perhaps deserves the most praise, the script is brilliant and full of inventive and funny situations and characters. Floor seven and a half, Floris the receptionist, and Lotte's home zoo provide a gateway to a very slightly off-kilter world that is fun and engaging before the film takes a darker turn. While my image of Jonze is of a very visual director, with the exception of a couple of scenes the film is not reliant on special affects, the puppet scenes were a pleasant surprise and wonderfully directed.

The cast is great, led by John Cusack as the obsessively passionate puppeteer and Cameron Diaz in a role that makes you wonder why she doesn't make more of an effort to find interesting material to work with (although looking at her back catalogue this seems unfair, it's just her Charlie's Angels image sticks out more than her better stuff). The man himself, John Malkovich doesn't actually have a big role in the film, but it appears this film helped him land roles in more commercial films, simply by giving his name more 'star' quality, it being in the title and all.

Being John Malkovich feels as fresh and inventive today as it was when released, thanks mostly to the genius script. I'm now very excited for Kaufman's adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (dir. Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger, 1943 UK)

David Canfield, Contributing Writer:

First, “Balderdash.” Next, “Poppycock!” Lastly, “Rot and we are not amused.” That’s my personal reaction to trying to squeeze out a review of this masterpiece in 300 words.

First: this is a film by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. If you aren’t familiar with them you should immediately pick up the Criterion editions Black Narcissus (1947), The Red Shoes (1948), and Peeping Tom (1960). Then write me a thank you note and enclose money. Then go find Stairway to Heaven (1946) and Tales of Hoffman (1951), and just keep going. They were one of the great filmmaking teams in history and to watch their films is to be awash in the most vivid technicolor possible and follow some of Cinema’s greatest characters through adventures that will inspire, even repulse, and provide fodder for your own dreams.

Blimp tells the story of Clive Candy, a British nobleman whose fourty years in the military are marked by acts of foolishness, heroism, pompousness and huge humanity. Powell and Pressburger treat each incident with consumate skill. I smiled constantly, I was deeply moved, I questioned his judgement, I felt for him in his growing sense of obsolescence. It is nothing less than the story of a life lived by a flawed human being. Forget the grand performances here, the aplomb with which Powell handles a duel by letting us hear it rather than see it. Instead we see a vast and quiet snowfall that lends the conflict a sense of grace that only makes sense later. Love, the kind that is felt but must remain undemonstrated, mixes with relationships marked by deep devotion and care for the other. Forget all of the above because ultimately Blimp is more than the sum of its parts, somehow more than a movie. Available on Criterion, Make sure to get the Blu-ray.

Wall-E (dir. Andrew Stanton, 2008 USA)

Winner of the Academy Award, Golden Globe and BAFTA for Best Animated Film

Dylan Sharp, Contributing Writer:

I don’t feel particularly guilty about missing Wall-E, but I chose it because I’ve been smugly dismissing the Pixar phenomenon for twenty years. People tell me that these new animations are good for all ages, but in my mind I always respond with “hmmm… kid’s stuff. I’m far too mature for this”- pretentiousness. And really, these types of animations seem to be where the CGI so adored in the past twenty years can really be employed as a consistent aesthetic. Have I been missing something?

Yeah the CGI looks cool, way better suited for sci-fi than for the weird anomalous flames and cartoony monsters that pop up in human worlds and try to ‘act natural’. The huge dust clouds and solar flares look more epic and ‘real’ than in live action movies. So I can see how people got into the movie and others like it as pure spectacle. Every object is ‘crafted’. So computers can create Art after all. Good for them.

The story? Yikes. Way more for kids than adults. I can’t really get into cute robots falling in love or fondling trinkets, and the ‘message’ about people being lulled into a pathetic, fat complacency by a dependence on machines (only to be startled back into humanity by humanistic robots) doesn’t really do it for me. Wall-E is American anime; if I was 13, I bet I would tell myself “this is totally for adults”. But so much whimsy is hard to take. Now that I’ve finally seen a contemporary animation I feel better about myself and I’ll probably watch another one with less angst in the near future. But at this point, it’s pretty much people playing with toys.

Rashomon (dir. Kurosawa Akira, 1950 Japan)

Winner of an Honorary Academy Award, winner of the Golden Lion and Italian Film Critics Award at the Venice Film Festival

Ernesto Zelayo Minano, Contributing Writer:

Rashomon felt a lot like one of those stories or rumors that starts out with “This happened to a friend of a friend.” A story that’s been told so many times that the details inevitably become hazy and in the end, you have no idea what actually happened. There are four different versions of the same story here, and it could go on forever, changing a few key details each time.

Nowadays, the concept of telling the same story from different vantage points has been done to death, but I can see how this must have been incredibly innovative back in the day. For me, however, it’s more of an experiment in narrative than an actual story, since we never get to see what really happened in the woods and there is no actual resolution. I have no clue if the baby at the end was supposed to signify anything.

Mifune Toshiro towers above everyone else here, a cast of actors who are either too solemn or low-key (funny how the husband barely says a word, and even when he does it’s through someone else), or go for theatrical histrionics (the wife). Mifune strikes the perfect balance, going from cackling madman to suave, handsome swordfighter in the blink of an eye. The man has presence to spare, and the one thing that stuck with me was Tajomaru’s constant, maniacal laugh.

Before sitting down to watch Rashomon, I associated Kurosawa with long, dense samurai epics. Thankfully, there’s nothing pretentious about this one; you can tell the director was influenced by traditional Hollywood storytelling, even if there’s no three-act structure here. As I said, it felt more like a film experiment, but it's still accessible and rewatchable. At least it made me want to see more Kurosawa movies. I have Seven Samurai at the top of a very long “To Watch” list.

The Elephant Man (dir. David Lynch, 1980 USA)

Nominated for 8 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, Winner of 3 BAFTAs, including Best Film and Best Actor

James Dennis, Contributing Writer:

There's much to like when David Lynch plays it straight; no funky experimentation and temporal jigsaws, just a linear narrative with great performances. Even if the subject matter of The Elephant Man is somewhat unconventional, much like 1999's The Straight Story, the techniques used to tell this painful story aren't.

I had feared the 1980s-era makeup effects used to depict the severe physical deformities of Victorian 'freak' John (actually Joseph) Merrick would scupper my empathy, yet somehow (partly by virtue of the black and white photography) they still work, if not entirely convince. Lynch treats it all with a deft touch, free of sensational trappings, though I found Michael Elphick's gaggle of taunting bullies too caricatured, too synthetic.

In a time when we're bombarded by leering shows such as The Man With The 10 Stone Testicles, it raises pertinent questions about how we treat - or rather gawp at - such minorities. Hopkins' Doctor Frederick Treves, ostensibly Merrick's rescuer from a life of poverty and abuse, questions whether he is "a good man" when troubled by the motivations for his actions.

Is it altruism, or veiled showmanship no better than Merrick's old freakshow master, as he allows a steady stream of high society guests to meet his patient? Then there's us, viewing, fascinated by his unfortunate, compelling and moving plight.

The Best Years of our Lives (dir. William Wyler, 1947 USA)

Winner of 8 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor, Winner of the BAFTA for Best Film From Any Source and the Golden Globe for Best Picture - Drama

Jim Tudor, Contributing Writer:

Boasting major stars (Myrna Loy, Fredric March), a major director (William Wyler) and a ripped-from-the-headlines relevance, 1946's The Best Years of Our Lives not only earned its acclaim (Oscars galore, and continued adoration), but remains relevant. Although its nearly three-hour duration allows for plenty of glossy torrid drama that Hollywood specialized in (young Teresa Wright falling in love with the married Dana Andrews), Best Years' theme of displaced servicemen returning from the war, counterbalanced with a palpable public dread regarding how to make room for these veterans, feels dangerously topical.

Although the name actors quite effectively carry the show, it is the presence of double-amputee Harold Russell, sporting a pair of hooks for hands, that fuses Best Years with its lingering vitality. Russell's work here is the very definition of “supporting actor”. The texture and reality he contributes (via his naturalistic acting) is brave, properly endearing, but never sappy.

Some may feel that Best Years wrapping up as nicely as it does for the characters is a cop-out in terms of its major themes of harsh re-integration and struggle, but we must remember that this is studio-system Hollywood, where the sight of a man with prosthetic hooks on screen was a bold move in itself.

At one point in the film, Russell's character announces the $200/month that Uncle Sam is providing to him. Although that might've been a lot of money in 1946, it is now a striking tell of how far we've failed to come. Nowadays, just getting the proverbial $200 has proven challenging for some. In the U.S., the string of harrowing news regarding the systemic troubles of current service people and veterans (V.A. backlog, payroll issues, The Invisible War, etc.) is a heartbreaking reminder that Best Years' themes are as germane as ever.

The Best Years of our Lives (dir. William Wyler, 1947 USA)

Winner of 8 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor, Winner of the BAFTA for Best Film From Any Source and the Golden Globe for Best Picture - Drama

Pierce Conran, Contributing Writer:

The Best Years of Our Lives is one of those big names in classic Hollywood Cinema that I just never got around to. Looking back on it, I’m not quite sure how it ended up on this list. I suppose it’s a name that has cropped up enough times over the years to make me feel as though I’ve missed out on something. I wonder exactly what it was that I’ve been hearing, as I was completely unprepared for this three-hour returning WWII veteran family drama.

Three soldiers, from different backgrounds and areas of the military, meet on the final leg of their journey back home after years away during the war. They’re all excited to be home but nervous of what may have changed or how much the intervening years may have affected them. Particularly the young Homer, who now has hooks in place of his hands.

The adjustment hits them hard as their families have indeed changed, their PTSD impacts their sleep or they’ve been away from work too long. It’s all rather effective, if a little on the nose, but considering similar narratives we’ve seen over the past decade following the Iraq War, the 1946 film was likely ahead of its time.

It won seven Oscars and was directed by William Wyler, a name behind a great many classics, though mostly films that I’ve found good, if unremarkable. Unlike Howard Hawks, Billy Wilder or Alfred Hitchcock, there’s something a little drab in Wyler’s style - he’s very functional and reliable. The same can be said of The Best Years of Our Lives. It’s a good film with a solid message that is well conveyed, but it doesn’t have the staying power of other classics from the period.

A Fistful of Dollars (dir. Sergio Leone, 1964 Italy)

Shelagh M. Rowan-Legg, Contributing Writer:

I don’t know if it was the quality of the Youtube video, or the quality of the dubbing, but I was never quite sure what was happening in A Fistful of Dollars. Still, it really didn’t matter. This movie seemed to be much more about style than substance. While not a fan of classic westerns, I love recent neo-westerns that are more self-reflexive of the genre (such as Meek’s Cutoff, Dead Man and Blackthorn). And spaghetti westerns are another branch away from the tradition, so I’m not surprised that I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Clint Eastwood looks and sounds like he was dropped onto an alien planet in the film. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. He is the strong, stoic type who in his westerns (and other films) talks more with his chest and gun. To then have this character dropped into the seeming barren landscape of Texas/Mexico, which is really Italy, in a film directed by an Italian, surrounded by Italian and Spanish actors, cultures known for fervent hand gesticulation and verbosity, well, I laughed a lot. I’m not sure if that was Leone’s intention.

I realize that spaghetti westerns were/are meant to be homages to traditional westerns, but perhaps watching them so much later they feel more like loving parodies. It’s hard to separate them from their location, in a continent so deep in history that their “wild west” came and went centuries ago, and the figure of the cowboy outlaw feels out of place. Though unlike classic westerns, the brutality is far worse, adding a greater sense of danger (again, likely the result of these being European films, which are more open with sex and violence in film). I’ll definitely be adding more spaghetti westerns to my viewing list.

More about Lists of Shame 2013

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Friday One Sheet: LIVING THE LAND

Now Playing: BLADES OF THE GUARDIANS and Some Other Movies

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada