Chinatown (dir. Roman Polanski, 1974 USA)

Winner of the Academy Award for Best Screenplay, nominated for 10 more including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Actress; Winner of 4 Golden Globes including Best Picture - Drama and Winner of 3 BAFTAs including Best Director.

Todd Brown, Founder & Editor:

Over the past few years a great deal has been made about the explosion of 'Nordic Noir' and the global popularity of these sorts of intelligent, stylish crime films. While watching Polanski's Chinatown the reason for their popularity became immediately apparent: they're the exact sort of film that Hollywood used to take great pride in but has since completely abandoned in favour of effects-driven blockbusters. Dragon Tattoo is the Chinatown of today.

Polanski takes great pride in playing with the tropes of film noir here, building a compelling story out of a very bland-seeming scenario (civic corruption over the water supply? Really? Really) and he works the form spectacularly well. But the real engine that keeps the Chinatown car running is the magnetic performance by Jack Nicholson. While Nicholson has certainly aged more gracefully than peers such as Robert DeNiro, say, it's still a more than worthwhile exercise to go back to his early work and catch him at his prime. And his prime was rather primal.

I was already well familiar with young Nicholson through work such as Five Easy Pieces and One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest but his performance here as J.J. Gittes is something else entirely, something that contains his raw and restless energy and focuses it into something not really more polished, but more layered and nuanced. The man's a monster of a performer and this may be his finest moment.

Chinatown (dir. Roman Polanski, 1974 USA)

Winner of the Academy Award for Best Screenplay, nominated for 10 more including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Actress; Winner of 4 Golden Globes including Best Picture - Drama and Winner of 3 BAFTAs including Best Director.

J. Hurtado, Contributing Writer:

I don’t know why I’ve avoided Chinatown for so long. Like every other title on my list of shame, it’s a film I’ve owned in many iterations, from VHS to DVD to special edition DVD, and now Blu-ray. I suppose it’s the compulsive collector in me that will allow a film with this kind of cache to sit on a shelf without any particular sense of urgency to actually watch it. Thank heavens for this column or who knows how many more years would’ve passed before I managed to see it.

I can’t say I knew exactly what to expect going in. Of Polanski’s films, this is certainly the elephant in the room. I’ve seen many fantastic, yet apparently lesser, films of his, but Chinatown is the one everybody knows, and with good reason. This is almost certainly Polanski’s most straightforward, least gimmicky film, and therefore the one most likely to garner mainstream success. Not to mention the fact that it’s a damned good movie with an amazing group of impeccably cast performers. Every single actor on screen is cast perfectly, and this is more than half the battle in turning what could’ve been a simple procedural into an all time classic.

Of course the film belongs to a young and vital Jack Nicholson, who is far from the parody of himself that he has become in recent years. Nicholson’s hungry private dick on the search for just enough truth to keep his own ass out of trouble is a powerhouse performance. However, for me that was expected, it’s the supporting cast that really makes the film. Faye Dunaway is perfectly cast as the ridiculously melodramatic Mrs. Mulwray, in a performance that predates and perhaps even out-crazies her career-defining role (for me, anyway) in Mommie Dearest. Her confessional moment regarding the identity of a particular young woman to Nicholson’s Gittes is the stuff dreams are made of. Then there is John Huston, who is always a pleasure to watch, cast as the surly and impenetrable water baron Noah Cross.

The plot, when described out loud, sounds deadly boring, but the script, performances, and direction turn Chinatown into a marvel of modern filmmaking. It is a film that is just as fresh today as it was almost forty years ago.

Chinatown (dir. Roman Polanski, 1974 USA)

Winner of the Academy Award for Best Screenplay, nominated for 10 more including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Actress; Winner of 4 Golden Globes including Best Picture - Drama and Winner of 3 BAFTAs including Best Director.

Andrew Mack, Contributing Writer:

There was a time, not so many moons ago, that I wanted to delve into the film noir genre. I mean seriously dig into those films from the 40s and early 50s. I never got around to it; my effort shall be saved for another times perhaps. But other than Chinatown (which bowed in the Summer of 1974 which means it's nearly as old as me - crikey!) I’ve seen only a couple other worthy - and contemporary - nods to the genre; either in direct accordance to, or, an interpretation of the genre.

The only thing I knew about Chinatown up until my viewing was that it was noir-ish. And there was this iconic image of Jack Nicholson with a bandage over his nose. Gosh, he spends a good third of the film with it covering his schnoz. But that image stuck out even though I’d never seen the film. I knew what movie that was from! Now that I know how that bandage got there my affinity for knives has been quelled somewhat. Damn you Polanski! (He should be damned for other things obviously. Knives are the least of my worries with him around).

What impressed me most about the film was Robert Towne’s screenplay. Though it was not filled with what I would have expected to be the vernacular of the genre (c’mon, beat it, scram, you see. etc) it's still as sharp as a tack. And though I have come to understand that Polanski made changes to the ending of the film to make it more tragic, it still did a pretty good job of keeping me on my toes throughout. There are lots of twists and turns without being obvious about it. Chinatown was nominated for 11 Oscars and Towne’s screenplay was the only winner in its category.

I am unsure what I have gained from this month’s viewing. Chinatown is a fine film and all. But I think if I wanted the full-on noir experience I am going to have to go back to those films from the 40s and 50s to really appreciate the genre. I appreciate Chinatown for what it is though.

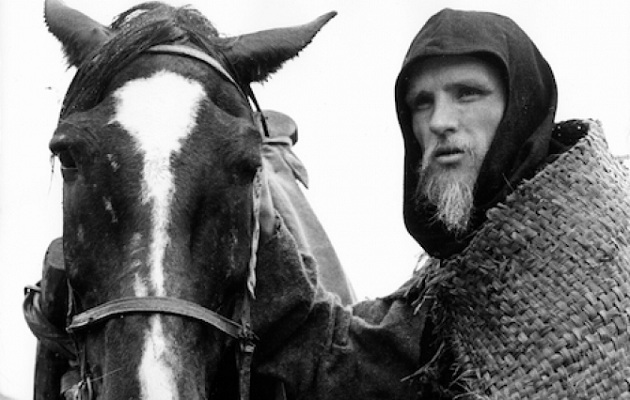

Andrei Rublev (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966 Soviet Union)

Winner of the FIPRESCI Prize at the Cannes Film Festival

Peter Martin, Managing Editor:

Russian Cinema is one of my blind spots, beyond an occasional dip into the Sergei Eisenstein pool of classics, owing more to limited time and opportunity than purposeful avoidance. As a step toward curing that oversight, I began with Andrei Tarkovsky's striking, though relatively modest Ivan's Childhood, before tackling his far more challenging second feature.

Indelibly etched in pain, Andrei Rublev proves to be a historical picture that spans the centuries in its connection to the essence of human existence. Grounded, literally, in mud and clay and dirt and rain, the bleak settings marched slowly into my subconscious, so that by the end I felt at one with the rough-hewn people struggling to survive in a hostile environment. Incredible cruelties are meted out to man and beast alike, and are even more disturbing because they're depicted in such a mundane manner.

I'm certain that watching the movie at home diminishes the experience. Yet it's still sobering, unsettling, emotionally draining, and absorbing, penetrating my usual defenses with images that are haunting and visually arresting. It's a tour-de-force that is completely beyond my ability to comprehend after only one viewing.

Andrei Rublev (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966 Soviet Union)

Winner of the FIPRESCI Prize at the Cannes Film Festival

Shelagh M. Rowan-Legg, Contributing Writer:

I wish I could have seen this film on a big screen; Tarkovsky demands it. Having written a paper on Solaris a few years ago, I was surprised at how long it took me to get around to Andrei Rublev. Certainly, one can see Tarkovsky’s influence reaching into even today. For some reason, I kept thinking of Paul Thomas Anderson’s work, in terms of the discentred narrative, long takes, and obsession with the metaphysical (especially in The Master). So needless to say, I loved Andrei Rublev.

Not so much a biopic of the great artist as a study of the dark ages in Russia, the phrase that kept coming to mind was ‘stark melodrama’. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a film set in the dark ages that doesn’t portray life as nasty, brutish and short, and the use of black and white compounds this. Considering how flooded we are with films that insist on rapid narrative, constant barrage of special effects and CGI, and the insistence on the hero, Andrei Rublev is so refreshing. I want a story that takes its time, I want scenes where two people talk about art one moment and the meaninglessness of life the next. I want long shots of a barren yet beautiful landscape.

Tarkovsky was interesting in altering the spectator’s conception of time; certainly, he achieves a distortion of cinematic time (Gilles Deleuze would be proud), by asking the spectator to rethink how we perceive time within film. This film follows several years, and we are given signposts to the passage, but it feels like the space of a day and a thousand years at the same time.

How often to we see wide landscape shots filled with people (actual people, not CGI) anymore? I realize this is a financial consideration, but still, it looked marvelous, even on my laptop screen. And I wish there were still directors like Tarkovsky, refusing to pander to the audience and instead moving them towards the difficult and sublime.

Andrei Rublev (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966 Soviet Union)

Winner of the FIPRESCI Prize at the Cannes Film Festival

Niels Matthijs, Contributing Writer:

It's been a while since my last Tarkovsky. When I just started to get into film I watched four of his most-lauded works (Solaris, The Mirror, Stalker and Nostalghia) but apart from Stalker nothing really gelled. While I do appreciate the ideas behind his style of filming, the often heavy-handed Russian approach puts me off.

Thematically Andrei Rublev is pretty much what you'd expect from a Tarkovsky film. Hardcore ARP-cinema (art, religion, philosophy) in full effect, but delivered in a more narrative and straight-forward way. At times it felt like I was watching Bergman instead of Tarkovsky and that really doesn't bode well.

The film roughly follows the life of icon painter Rublev, split into eight individual segments. While the first one wasn't too bad, the second segment was pretty dialogue-heavy and marks the start of a film filled with religion-inspired issues and problems that clearly weren't my own. At one point the question is raised how one should live his life dealing with guilt, knowing that God will forgive his sins when he dies. To me this is as interesting as wondering how many grains of sand it would take to fill up my living entire living room. I simply don't have any connection at all with this kind of material.

Judging from the 5-minute epilogue (showing nothing but paintings from Rublev), Tarkovsky was a pretty big fan of his work. I clearly wasn't, which didn't help much either. Apart from a few shots the visuals didn't really appeal to me either, the soundtrack was better but the sound editing was extremely lazy. Just music playing in the background, often oblivious of what was happening on screen.

I watched the 205 minute version, looking back I really shouldn't have. After the third segment I was bored out of my wits, with 5 more segments to go. It took a lot just to get to the end of the film. There simply wasn't anything here that caught my attention. Normally I can deal pretty well with longer films, even when I don't care much for them, but Andrei Rublev truly felt like a chore. Never again.

Barry Lyndon (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1975 USA)

Winner of 4 Academy Awards including Best Score, Best Cinematography, Best Costume Design and Best Art Direction; Winner of 2 BAFTAs including Best Director

Ryland Aldrich, Festivals Editor:

The half-way point of our Full Disclosure series brings the first in my favorite auteurs section. These are the films that I am truly ashamed to admit I have never seen. Future directors will include Richard Linklater and David Lynch, but the first shameful moment is brought to us courtesy of the master Stanley Kubrick and his 1975 costume-classic Barry Lyndon. While I've long known this film existed, the most I've seen of it was from Rodney Ascher's recent The Shining conspiracy-doc Room 237, in which one of the disembodied theorists purports that Kubrick's propensity for hiding meaning in The Shining was partly due to his boredom after finishing the melancholic Barry Lyndon. With that less than glowing recommendation I set forth to finally cross the last well known feature off my Stanley Kubrick bucket list.

Based on a mid-19th century novel about a mid-18th century Irish gentleman, Barry Lyndon is nothing if not a tale of two halves. It's broken in two acts with both title cards and an intermission and the two parts may as well be separate films. The first half is a thrilling tale of the young rogue as he adventures across Europe getting into scrapes and duels and somehow finding his way out of trouble time and again. Unfortunately, the second half slows to a crawl as our protagonist becomes embroiled in domestic affairs that prove far less exciting than his earlier sojourns.

That's not to say this isn't a brilliant film and it's easy to see why Kubrick's team brought home the Oscars for Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction, Best Costumes, and Best Score. Technically the film is perfect and the performances are top notch as well. The scene of Barry smoking a pipe alongside the Countess as they carriage through the countryside at the opening of the second act is the kind of subtle Kubrickian genius that makes one gasp in delight. But perhaps it's because those moments are slightly more oblique than in his other films that Barry Lyndon is one of his slightly more often overlooked films. What's plainly apparent from watching it for the first time is that even a slightly overlooked Kubrick is still a masterpiece.

Barry Lyndon (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1975 USA)

Winner of 4 Academy Awards including Best Score, Best Cinematography, Best Costume Design and Best Art Direction; Winner of 2 BAFTAs including Best Director

Jim Tudor, Contributing Writer:

Whenever the branding of “Kubrickian” is leveled upon another filmmaker, be it positive or negative in intent, it could be Barry Lyndon that is more purely being referred to, even more-so than the far better known 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange or The Shining (the latter two being the entries that chronologically sandwich it, auteur/production-wise). This is not to say that Barry Lyndon is Stanley Kubrick’s most assuredly styled film, or the one that is somehow most “his own”.

Kubrick is of course one of the most definitive and identifiable filmmakers ever, with a unified filmography like few others. But with his 1975 period epic Barry Lyndon, he might simultaneously be at his extreme best and worst. The deliberate pacing, the apparently detached storytelling demeanor, the intensely precise visual framing, the sense of cinematic innovation, and the raw unmitigated power of it all... For better or worse, Barry Lyndon is exactly the kind of film that would never exist were it not for the existence of Stanley Kubrick, and his ability to will it into reality.

Although I'd never seen Barry Lyndon in its entirety, I was no stranger to it. As a college student, I attempted to watch the three hour opus in the middle of the night. Between the hour, my own denied exhaustion, the movie itself, and the washed-out library-issued VHS tape I was playing, I calculate I made it about one hour in. (I am not alone – no less than the esteemed David Thomson admits that it's the first movie he ever fell asleep during). This time, half a lifetime later, it took me two sittings and no shortage of caffeine and sugar to complete. I still passed out three times, making a point to backtrack once I awoke.

In college, an instructor who was also a professional gaffer (and renter of filmmaking equipment) profanely took the film to task for its “showy” insistence upon using natural lighting throughout. Indeed, cinematographer John Alcott even developed special lenses to capture the 1700's old world European etherial aesthetic that Kubrick was clearly all about. I took no such issue. And although the pacing might be the very definition of “deliberate” to some, a closer inspection of the editing style will reveal that it's no Turin Horse.

The sleep-inducing power of Barry Lyndon must lie primarily on the shoulders of Barry Lyndon himself (Ryan O'Neal, not so much miscast as in over his head at moments), an uninteresting lout whose ups and downs are of his own selfish making. Through the Seven Years War, wealth, poverty, and personal tragedy, our protagonist is frequently little more than a flawed cypher, demonstrating that no matter what opulence and misfortune befall him, the one thing he'll always be is perpetually imperfect. So too is Barry Lyndon. Even by the end, when he does perhaps the first selfless thing in his life, the payoff is only amputation - emotionally and physically. But perhaps that is Kubrick's point.

Days of Being Wild (dir. Wong Kar Wai, 1990 Hong Kong)

Winner of 5 Hong Kong Film Awards including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor; Winner of the Golden Horse Award for Best Director

James Marsh, Asian Editor:

While Wong Kar Wai's In The Mood For Love was one of the very first Hong Kong films I saw, it has taken me a very long time to explore the rest of his back catalogue. Days of Being Wild is the second of his films I have watched during this feature (after Happy Together) and with the exception of his sole English language effort, My Blueberry Nights, I am now all caught up.

Unsurprisingly, the impact of Days of Being Wild is somewhat diluted watching it more than 20 years after the fact and having consumed all his subsequent work beforehand. There are few surprises in this meditative tale of a emotionally inert playboy in 1960s Hong Kong, who flippantly tosses women aside, while living off his mother's money. However, when he learns he was in fact given up at birth, his life is thrown into turmoil and he heads off to the Philippines to trace his family roots.

As is the case with all Wong's films, the plot comes a distant second to the mood and tone of the piece, while many of the director's favourite recurring themes - time, memory, heartbreak etc - are introduced for the first time. Days of Being Wild also marks Wong's first collaboration with Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle, who gorgeously photographs the kitsch interiors of the period, while also experimenting with some invigorating handheld explorations of Manila towards the end of the film.

In and of itself, Days of Being Wild is a tender, tragic and beautiful little film, with a cast brimming with many of the day's biggest young stars: Leslie Cheung, Maggie Cheung, Andy Lau, Carina Lau, Jacky Cheung and - albeit very briefly - Tony Leung Chiu Wai. All that said, approaching the film so late in the day, and late in my own exploration of Wong's oeuvre, it is difficult to honestly argue I have gleaned anything new from having seen it. Everything that is in this film is also, in one form or another, in the rest of the director's body of work. But perhaps that is more a criticism of Wong Kar Wai's particular obsessions, than a fault of Days of Being Wild.

One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest (dir. Milos Forman, 1975 USA)

Winner of 5 Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor; Winner of 6 BAFTAs including Best Picture; Winner of 6 GOlden Globes, including Best Picture - Drama

Simon de Bruyn, Australia & NZ Editor:

I missed my last two films (On the Waterfront and The Planet of the Apes) so am bouncing back into things with a film that unlike those two - which really belong to a list of obligation more than shame - is truly something I’ve been embarrassed to admit not having seen. Like all the films on my list so far, I went into One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest with the looming spectre of the film and its iconic characters dominating my perceptions. So it was interesting to have them both simultaneously confirmed and denied.

On one hand Cuckoo's Nest was everything I expected, while also being nothing like what I imagined. I knew about Nurse Rached, but had pictured her to be more of an older Miss Trunchbull character; I knew about the escape from the facility but also had it pictured completely differently, and thought it took up more of the movie. I had no idea it would be as loud, violent and painful to watch (the mistreatment of patients was horrifying); nor that it would be so explicit. I also had no idea it would coalesce a bunch of films I’d never linked - namely The Great Escape, Cool Hand Luke and The Shawshank Redemption - into a very unified (and now completely obvious) thread of movies that have clearly influenced each other chronologically.

I had some suspicions it would be a downer, and think this may have been a reason I had avoided it for so long, but didn’t expect it to be a crushing defeat of a film. Yes, there’s the last bit, the triumphant bit, but having just finished watching it 20 minutes ago I don’t feel that yet - just overwhelming, crushing sadness. Fuck you, Nurse Rached.

Ugetsu Monogatari (dir. Mizoguchi Kenji, 1953 Japan)

Winner of the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival, nominated for the Academy Award for Best Costume Design

Ben Umstead, East Coast Editor:

As a teenager my gateway into non-English Language Cinema were the films of Kurosawa Akira and his countrymen. There was something about the way Japanese filmmakers approached the medium that my young mind found vital, immediate and thrilling. Names like Ozu, Teshigahara, Kobayashi, Imamura and Gosha rolled off my tongue with admiration and the utmost respect.

But there was one name in the pantheon of Japanese masters I for whatever reason ignored: Mizoguchi Kenji.

If there is one title then on this list that I feel truly ashamed of not seeing earlier it is Ugetsu, Mizoguchi's celebrated fable on the corruption of men's hearts and the wise women who are dragged down by their greed.

A loose adaptation of 18th century novelist Akinari Ueda's book of moral tales, set amidst the civil wars of the 16th century, Ugetsu follows potter Genjurō, his wife Miyagi, and their neighbors Tōbei and Ohama. Genjurō dreams of becoming rich off his pottery. Tōbei aspires to be a great samurai. Their wives consider them fools for such brash dreams, and think they should be grateful for what they do have: food, family and a roof over their heads. Soon war is at their doorstep, turning their world upside down, and sending the men off into madness, with their wives scrambling after them.

A mesmerizing tale often wrought with tension and heartache, Mizoguchi's filmmaking is also lithe and gentle, his camera passing over villages and markets, ruins and misty lakes with a grace that is haunting. His heart sings for the plight of these women and the burdens they must endure.

Though we only spend a little over 90 minutes of screen time with these families, by the bittersweet end I couldn't help but think, "what a long, strange trip it's been... and I'm all the better for it." If that is not a sentiment rising from the essence of great storytelling, than I don't know what is.

Brother's Keeper (dir. Joe Berlinger/Bruce Sinofsky, 1992 USA)

Winner of the Audience Award (Documentary) at the Sundance Film Festival

Jason Gorber, Featured Critic:

“We’re loved by indie filmmakers, and hated by documentarians” – Joe Berlinger.

I first heard about this film when it showed up on a top films list by Ethan Coen. In preparation for the third segment that played at TIFF a few years back, I’d delved into Sinofsky and Berlinger’s Paradise Lost series in marathon fashion, and Berlinger’s Paul Simon doc Under African Skies was one of my own favourites from 2012.

I was intrigued enough to go back to where these guys started. Berlinger and Sinofsky met working for the Maysles Brothers, and took it upon themselves to toil on this project on weekends and holidays. They used their credit cards and second mortgages to self-finance a film about a group of hick farmers in upstate New York. This isn’t the bucolic Madison County of Eastwood/Streep fame, this is the hardscrabble farming community where some bumpkin boys lived like they were part of another century. When one was accused of killing his ailing brother and bedmate in his sleep, the national media descended to make hay of the story. These filmmakers followed, and rather than elicit soundbites, they put in the time, gaining both exceptional access and an even more exceptional narrative.

It’s easy to see in this film the template for many later works, including the Paradise Lost series. What was lost on me on first viewing, given how commonplace such devices have become, is how overtly cinematic the film is. Shot on 16mm, using some clever jump cuts and sweetened audio, as well as a commissioned score, the movie doesn’t play as a dull documentation but rather as a non-fiction feature film, with a sweeping narrative shared with many other works at the multiplex.

On the disc’s commentary, Berlinger talks of creating ”feature film-like moments, merging the best of fiction filmmaking techniques with a documentary subject”, much to the irritation of the established documentary community. Ten years after those comments, and some two decades after the film was shot, it’s a testament to their craft that this is the new norm for exceptional non-fiction works.

Berlinger argues the film is “not giving Truth with a capital T, it’s with a small t”, a fact not lost on modern audiences well aware of such manipulations in even more overtly “pure” documentary forms. If even the most verité-styled work trades in verisimilitude, why not concentrate on making an enjoyable film rather than one slavish to some epistemological purity?

Later, with Paradise Lost II, the filmmakers went too far on this manipulation, something they agreed with during discussions at that TIFF screening. I found it refreshing that the filmmakers admit on the commentary that it’s likely that the brother did murder his sibling, despite the sympathies (and acquittal) that are captured on film. The truth, in this case, is more complicated than that. Brother's Keeper is a film that asks rather than answers questions, and frames this discussion in a visually beautiful and narratively pleasing way.

The Double Life of Veronique (dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1991 France/Poland)

Winner of the Best Actress Award, FIPRESCI Prize and Ecumenical Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival

Ard Vijn, Contributing Writer:

Watching this month's film challenges yet another huge gap in my European movie knowledge: The Double Life of Veronique is my first film by Krzysztof Kieślowski. And while I'm baffled by it, I do feel the urge to seek out his other films as well.

When Kieslowski was still alive, my interest in Non-Hollywood Cinema was increasing, but still very much in its infancy. And anything out of Eastern Europe got the standard labels attached to it by teenage me: slow, depressing, boring.

Had I seen The Double Life of Veronique then, it would probably have reinforced that stigma, as it is a powerfully meditative film. In the end, The Double Life of Veronique left me confused, as I did not understand the story or what the director was trying to tell me with it. For a film so often praised, it is rather hard "to get". But it also is a gorgeous one, as Kieślowski seems to be painting with light, color, movement and sound. There is a love of Cinema, feelings, and beauty in general here, which covers the whole film like a warm blanket.

So I cheated for this article, and started reading other people's reviews. Turns out I am not alone: many people think this film is vague, and several attempts to make sense of it all have produced interesting (and sometimes amusing) theories. The confusion I felt is probably intentionally induced by Kieślowski as a tool to make me empathize more with Veronique, longing for connections which may or may not be there.

Like its protagonist, The Double Life of Veronique may not be "my type", but is certainly easy on the eye, and obviously a display of talent. And I am now seriously interested in Krzysztof Kieślowski. Anyone care to suggest which of his films I should watch next?

La Dolce Vita (dir. Federico Fellini, 1960 Italy)

Winner of the Palme D'Or at the Cannes Film Festival; Winner of the Academy Award for Best Costume Design and naminated for 3 others, including Best Director

Joshua Chaplinsky, Contributing Writer:

There are two iconic images associated with Fellini's La Dolce Vita: Anita Ekberg frolicking in Trevi Fountain, her bosom rippling like the water; and Marcello Mastroianni astride an intoxicated woman crawling on her hands and knees. These images made up the sum total of my knowledge going into the film. Both vixens are blonde, so I'd always assumed they were the same woman (they aren't) and said woman was a main character in the film (she really isn't).

The synopsis on the Netflix DVD sleeve didn't do much to correct my assumption, as it paints the film as Marcello's pursuit of Ekberg's character (Sylvia). So there I was over an hour into my viewing, expecting another 90 minutes of Sylvia's airheaded antics. Thankfully, the vapid starlet was a mere speed bump on Marcello's road to hell, because I couldn't stand her. What did Marcello see in her? How she could be admired for anything other than her voluptuousness is beyond me. Unfortunately, by the time I got to the bleakness of the film's final sequence, I found myself yearning for her hollow brand of joie de vivre. The good life indeed.

It's amazing how little has changed in the 50+ years since Fellini brought his vision of tabloid journalism to the screen. Sure, the technology has been updated and our access has expanded, but photogs are still chasing down celebrities in cars, creating their own version of the news (just ask Princess Diana). It's not that far removed from Kim Kardashian and TMZ. I wouldn't call Fellini prescient; he wasn't predicting the future, celebrity culture just hasn't evolved much since then, therefore, neither have we. La Dolce Vita is practically screaming for a modernization, as unnecessary as that would be. Hell, Teenage Paparazzo is practically the real life version.

And that's what I found so thrilling about the film. It's still relevant — especially to an American audience — as old and European as it is. It's so on the money it's scary. La Dolce Vita is a must-see for anyone interested in the inner workings of popular culture and the facade of fame. Another worthy subtraction from my list of shame, and a shame I hadn't seen it sooner.

The Big Red One (dir. Sam Fuller, 1980 USA)

Premiered In Competition at the Cannes Film Festival

James Dennis, Contributing Writer:

And so comes the first disappointment in my list. For the most part I found Samuel Fuller's semi-autobiographical war flick desperately unengaging and, frankly, dull. My reasons for picking it revolved around Lee Marvin's commanding screen presence and my general fondness of half-decent war movies. I'm certainly no Fuller aficionado. I should point out that I watched the longer 2004 'Reconstruction' clocking in at around 150 mins and having undergone digital restoration.

Fuller focuses more on character interaction than war-action, but as we track Marvin's infantry squad from country to country I felt no connection with them, no empathy. The faux tough-guy dialogue and vacuous personalities are little more than Hollywood placeholders. Episodic and rambling, even the sporadic battle scenes fail to stir, flatlining on the excitement front.

It comes across like a war movie caught between eras; directed in a perfunctory classical Hollywood fashion yet with a flash of bloody testicle for a more 'progressive' modern audience. Just three years earlier, Peckinpah managed to blend character-led drama, war-is-hell rhetoric and riveting battle scenes to far more compelling ends in Cross of Iron (1977).

I do wonder if the theatrical cut would have been punchier, but sadly not even the near endless fascination in watching Marvin's craggy face could keep me enthralled with the yawn-inducing drama.

City Lights (dir. Charles Chaplin, 1931 USA)

Kurt Halfyard, Contributing Writer:

Chaplin’s City Lights is generally noted for its poignant relationship between The Tramp and a blind flower girl, selling her wares to keep herself off the streets. It is curious to me that that particular plot doesn’t really get going until nearly half the film has elapsed. It’s not that the early slapstick vignettes are particularly bad, but it does take some time for the film to come to any sort of life. Seeing the film on VHS (no joke) with sound effects added to Chaplin’s wonderful score, I remain puzzled how the swallowed-whistle gag worked in silent cinema of its day. Perhaps someone offscreen doing the foley?

However, when The Tramp enters the boxing ring in an effort to win prize money to pay overdue rent (and hopefully an eye operation for his lady), the film sings. This might actually be the first film to feature ‘wire fighting’ as Chaplin is propelled from the top of the ropes to collide with his burly opponent via (not entirely) hidden wires. And this has nothing on the footwork and choreography of one of the actor/director's all-time great scenes. Joy! Less so is the on-again-off-again relationship the Tramp has with a suicidal and drunken millionaire, who is desperate for companionship at nights, and oblivious to his (often reluctant) drinking buddy in the morning.

But Chaplin brings it all home with an at first suspense-filled, then poignant, literally touching ending. While I am a Buster Keaton man through and through - his deadpan wit hits my sweet spot over sentimentality - there are golden moments hidden inside the pleasant filler of City Lights.

Enter The Dragon (dir. Robert Clouse, 1973 Hong Kong/USA)

Pierce Conran, Contributing Writer:

It's a hard thing to admit (at least to some people), but until now I had never seen a Bruce Lee film. Finally watching him in action after all these years was both a relief and a bit of a non-event. I suppose the latter was inevitable. One of the most iconic personalities of the 20th century, it’s hard to walk through life without bumping into him time and again. I’ve seen countless imitators, heard innumerable myths about his feats, hell I’ve even seen his statue on the Kowloon harbourfront (thanks to James, my tour guide in HK earlier this year!).

There’s no denying the magnetism of Lee’s overweening bravado. I was less impressed with his vocal acrobatics, though I know they are a grand part of his image. I could also plainly recognize his skill, but a full 40 years after the fact, I’d be lying if I said I was impressed.

My first Bruce Lee film was his last. Aside from the martial arts star, I must confess that I was a bit surprised by Enter the Dragon. Despite its reputation as a martial arts classic, not least for being the premature swan song of the genre’s biggest name, it really just feels like a cheap James Bond knockoff with a good dollop of chopsocky thrown in for good measure. Mind you, that’s not necessarily a bad thing as Enter the Dragon is quite a bit of fun. Ridiculous and undemanding, I can see how a great many films were influenced by it, for better of for worse. However, the film itself is a pastiche of much that has come before it.

I enjoyed but didn’t love Enter the Dragon and am just a little sad that I probably missed the boat on Bruce Lee fanaticism. That said, I do look forward to exploring the rest of his small body of work.

More about Lists of Shame 2013

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Friday One Sheet: LIVING THE LAND

Now Playing: BLADES OF THE GUARDIANS and Some Other Movies

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada