Jason Gorber's Cineruminations: ARGO and the "Truthiness" Doctrine

Argo is a delightful throwback film, echoing the kind of "political intrigue" style that was commonplace during the Nixon administration. The fact that Argo shares many characteristics with the likes of The Ides of March might be no mere coincidence. Forgetting the obvious point, that George Clooney is listed as a producer on both works, this film about events surrounding the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis fits in nicely with last year's politico-drama, joining a line of recent movies that Steven Soderbergh, Grant Heslov, Stephen Gaghan (Syriana), and a relatively small community of like-minded artists have been crafting of late, a group that Ben Affleck fits in with very well.

Argo demonstrates that Affleck's move to directing is laudable as he settles in comfortably with this loose community of neo-political thriller makers. Affleck's latest work both in front of and behind the camera seems at first to be miles away from the aesthetic doldrums that beset the actor only a decade back, when he was found himself habitually working with the likes of Michael Bay on giant action set-piece pictures. His rejuvenation as both a craftsman and a performer is indeed quite remarkable.

The historical facts that provide a basis for the story of Argo

have been fragmented over the last decades, much more so than more casual

events. For reasons of either national security or simple cases of Rashomon-like

differences of opinion, this is a story that has had many competing narratives

over the last several decades. Given the secrecy and explicit calls for deceit

that swirled around the tale, it's no wonder that getting at what "really"

occurred is a challenging thing. It would be unfair to completely judge almost

any film based on how strictly it adheres to facts, particularly one of this

nature. That said, if the film has the right to trade historical fact for dramatic

license, it must do so without sacrificing believability. In the end,

whatever the artists choose to invent, the audience better be along for the ride, or else the whole thing collapses into farce.

The historical facts that provide a basis for the story of Argo

have been fragmented over the last decades, much more so than more casual

events. For reasons of either national security or simple cases of Rashomon-like

differences of opinion, this is a story that has had many competing narratives

over the last several decades. Given the secrecy and explicit calls for deceit

that swirled around the tale, it's no wonder that getting at what "really"

occurred is a challenging thing. It would be unfair to completely judge almost

any film based on how strictly it adheres to facts, particularly one of this

nature. That said, if the film has the right to trade historical fact for dramatic

license, it must do so without sacrificing believability. In the end,

whatever the artists choose to invent, the audience better be along for the ride, or else the whole thing collapses into farce.

Argo doesn't pretend to be some sort of definitive telling, but it certainly traffics in what Stephen Colbert would call "truthiness." We judge what "feels" real with a film like this, using our "stomach brains" instead of our "head brains," as Colbert's logic dictates. We're left not simply with questions about whether Argo is loose with the facts -- it is, incontrovertibly -- but whether the games it plays with actual events leave us feeling that the story feels more believable.

Alas, at least for certain sections of the film, the story devolves into the preposterous. Forget needing to replace end credits, as was requested by one of the historical figures portrayed in the film, by the time we've got a car chase on a runway, all bets are off on linking this story with anything resembling a nuanced take on events.

[Thar be *spoilers* below for Argo, as well as for Compliance, Titanic and Brazil ... Ye be warned.]

In other works that purport to be "based on true events," elements of the narrative that are factual are so implausible that you spend much of the film assuming they're in fact contrary to what actually occurred. On first viewing, at least, these things can prove to be distracting, as you're watching something so clearly over-the-top that the actions strain credulity. A good example here is the oral sex scene in Compliance, an abuse that no screenwriter would have left in, yet is completely in keeping with what actually transpired.

Compliance provides an interesting case about this, for it's a film that perhaps drew too closely on the facts of the case without enough regard for the story as a whole. While I disagree with the charge, I was witness to an audience that simply lost investment in the story, complete with nervous, snickering laughter, at horrific-if-true, yet narratively preposterous moments, despite the fact that these events actually did befall those that were at the center of that particular story.

Often another twist is added to "truthy" films, where the filmmakers decide to ratchet up the tension using one or more cinematic clichés (think car chases, gun battles, and so on). One of my biggest challenges with James Cameron's Titanic is that it chose to artificially amplify what's clearly already a setting ripe for drama. Frankly, the audience doesn't need to have a gun battle on the decks of a sinking ship in order to feel tension; it's just a cheap and easy excuse to use a well-trod device to elevate the thrills of the piece. One would think the drama inherent in a sinking ocean liner would already be fodder enough to generate excitement and thrills, and yet the filmmakers chose to create slightly more intimate, melodramatic scenes of tension that could be alleviated within the whole.

These trite, throwaway moments that generate puffs of suspense do little more than obfuscate a more central, overwhelming drama, regardless of the fact that some go on to generate the largest box office receipts in history. In Cameron's sinky-boaty film, I can forgive handprints on steamy car windows and the melodramatic spectacle of much of the rest of the film, but the need to whip out a pistol and run through the dining room is going way overboard for me.

The same type of "value added" tension glommed onto an

already epic catastrophe can be found in much of the truly egregious Pearl

Harbor (starring, not coincidentally, a young buck named Ben Affleck). Bay

is hardly known for his subtlety, and the way that he crafts the film so that

we're left with a giant, heroic conclusion makes for some head-bangingly awful

moments. For those brief moments where we have pixel-on-pixel violence and

rampant scenes shot in the bays of Hawaii, the film is actually reasonably

effective. The scenes of planes attacking ships (forgetting the pace-breaking

insert shots of the cast) are downright thrilling at times, and despite knowing

the inevitable outcome, there are moments of genuine thrills bordering on

suspense.

The same type of "value added" tension glommed onto an

already epic catastrophe can be found in much of the truly egregious Pearl

Harbor (starring, not coincidentally, a young buck named Ben Affleck). Bay

is hardly known for his subtlety, and the way that he crafts the film so that

we're left with a giant, heroic conclusion makes for some head-bangingly awful

moments. For those brief moments where we have pixel-on-pixel violence and

rampant scenes shot in the bays of Hawaii, the film is actually reasonably

effective. The scenes of planes attacking ships (forgetting the pace-breaking

insert shots of the cast) are downright thrilling at times, and despite knowing

the inevitable outcome, there are moments of genuine thrills bordering on

suspense.

Pearl Harbor gets all the character stuff so very wrong, but (save for a jingoistic ending) gets quite a bit of the history right. Once you remove the made up characters, the large beats of film check off roughly actual events. Argo, on the other hand, is a taut, nuanced ensemble piece with great character interaction. It's so well made, in fact, that there will be audiences oblivious to the fact that it's lying to them for much of it about what actually transpired.

There is a key balancing act that "based on facts" films have to perform regularly -- how does one inject additional tension into a story where the outcome is well known to distract the audience from the inevitable conclusion? At the same time, these additions have to pass a virtual "smell test," they either stand out as distracting, or they conform to that "truthy" vibe, making us feel that these events are integral to the general narrative.

When done correctly, you get that magic moment, where concocted events are so intensely cinematic that you're made to feel that if they didn't happen that way, they probably should have. Patton and Lawrence of Arabia, for example, are roughly-hewn historical pieces that nonetheless are captivating on cinematic grounds, the various invented incidents almost supplanting the historical facts that were the basis for these projects in the first place.

Usually this can be done through obfuscation (gun battles on a sinking ship), or by focusing on fictionalized characters in a larger historical setting. This latter tack is the basis for almost all historical-themed works, freeing up the filmmakers (or novelists, for that matter) to explore the landscape of the historical moment without slavishly adhering to such things as facts.

This is why things get complicated when we're told a story that closely adheres to actual events, particularly reasonably contemporary events. I have no idea what really transpired during the rise of Facebook, but I don't really care, The Social Network completely exceeded my high expectations, and its flourishes of both narrative and style make one feel that rare, magical tingle that makes you stop giving a damn about what "really" happened and just like the tall tale being told.

When Argo works, as it does for much of its running time, it comes close to eliciting these tingles. By the time it goes overboard, by the time things get really crazy, it's less effective at maintaining that level of disbelief. Some may forgive these faults, already caught up in its bravura telling, perfectly willing to accept the preposterous. Alas, I was along for much of the ride, but by the ending, it all nearly fell apart for me.

Unlike other films slightly more coy about their historical origins, Argo isn't shy at all about the acts it's drawing from (and diverging from significantly). The film goes to enormous effort to make us feel that this is a story very much adhering to actual events on the ground, drawing a considerable amount of narrative power from this feeling that what we're watching really happened. While several characters are conflated in the film, and a few added for effect, much of Argo tells the tale of verifiable individuals and the travails that they overcame, using their real names and drawing upon their real histories. As if to hammer this point home, the closing credits pair photographs of the six surviving embassy workers with their respective actors, and the similarities are remarkable.

Unfortunately, the film is undercut by two elements: much of the work is complete fabrication, and much of the film, particularly the final third, feels like complete fabrication. The former is of course forgivable, the latter is not.

The magic trick of such a film, as above, is to incorporate those elements of fabrication without us ever questioning them. Focusing on a single CIA agent, for example (rather than the team that actually carried out the extraction on the ground in Tehran), or having all six of the embassy workers stay at a single location is the kind of simplification that actually helps serve the story very well. These are divergences from the facts, of course, but are more narratively elegant than actual events, and greatly benefit the script as a whole.

The issue crops up as a problem when these elements detract from the general narrative. For when the film ceases to be felt as real, when its verisimilitude fades, we're left with an ugly mess that often befalls such semi-fictional, often hamfisted works.

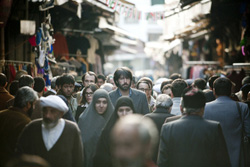

Two scenes show two very different aspects of how these

additions can either work or fail, depending on just how far the filmmakers

wish to push their audience. The scene where the seven Americans are asked to

go to the market to do some film scouting is one of the more effective in the

film -- sure, it's a blatant excuse to ratchet up tension, demonstrating

disunity in the group that will be overcome later in the work, but it's done

with skill and grace. The scene of them driving in the VW van through the

throngs of protesters is extremely well done, and the claustrophobic nature of

the market, with the secret surveillance of these individuals, is an integral

part to the narrative flow of the film. Even if this never happened (and based

on the notes of the agent it seems it never did), it's an example of a scene

that benefits the film as a whole.

Two scenes show two very different aspects of how these

additions can either work or fail, depending on just how far the filmmakers

wish to push their audience. The scene where the seven Americans are asked to

go to the market to do some film scouting is one of the more effective in the

film -- sure, it's a blatant excuse to ratchet up tension, demonstrating

disunity in the group that will be overcome later in the work, but it's done

with skill and grace. The scene of them driving in the VW van through the

throngs of protesters is extremely well done, and the claustrophobic nature of

the market, with the secret surveillance of these individuals, is an integral

part to the narrative flow of the film. Even if this never happened (and based

on the notes of the agent it seems it never did), it's an example of a scene

that benefits the film as a whole.

The same cannot be said for the bombastic, farcical action piece that underlies much of the film's conclusion. Again, we as an audience may be led to forget the historical fact that in actuality the biggest drama of getting the seven out of the airport had to do with mechanical delays of the taking off of the SwissAir flight. What can't be swallowed, however, is the last minute ratcheting up of tension to such a degree. Affleck whips out a vast collection of manipulative tricks, from the incessant ringing of an unanswered phone, to cross cutting between running troops anxious to stop fleeing individuals.

Like a bad cop show or comic book movie, Affleck sprinkles his film with moments of tension for tension's sake. The audience is made to feel anxious as our characters can't cross a movie set, or the President can't make up his mind, or a Republican guard can't get an answer to his phone call.

Much of this would have been forgiven, if they didn't ratchet it up even further. When the guards break down the glass to the boarding ramp, ram a jeep through a gate, and pursue like some mad Cannonball Run outtake a 747 passenger jet, the filmmakers have officially gone way too far.

The scene with the commandos/revolutionaries impotently waving their guns as the plane taxis for takeoff are the worst in the entire film, and where the believability of the whole is brought into question. This almost would be a minor setback if these contrived elements led to a "good story," but it's the opposite that's the case - this overwrought ending is neither historically accurate nor narratively plausible. It is that dreaded third thing, the "Hollywood-ization" of events, the bombastic overreach that Bay and his ilk are much derided for.

Let's take the ending of this film to a few (slightly hyperbolic) conclusions: the SwissAir corporation, of course, would be more than a bit aggravated that one of their flight attendants had been brutalized by guards while performing duties at an international airport. Incoming flights would be disrupted by the phalanx of cars strewn about an operating runway. Several other planes, some no doubt on final descent, would be forced into emergency procedures when the flight controllers are taken by surprise by marauding soldiers. Perhaps moments after our heroes leave, massive plane crashes litter the Tehran runway, as chaos reigns. For months afterwards, all civilian flights in and out of the country would have been disrupted, potentially plunging the nascent post-Revolutionary Iranian government into chaos.

Of course, none of this happened. Nor, of course, did almost any facet of the ending of Affleck's story -- sure, our heroes get on a plane, but the rest of the drivel, the guns, the interrogations, the whole lot, are as fabricated (and frankly ridiculous) as the paragraph I wrote above.

Despite the vast majority of the film being elegant and downright restrained, it's as if Affleck and company couldn't help themselves by the time they reached their conclusion. They felt they had to slather whipped cream atop their sundae in order to appeal to our basest narrative needs, and it's a real knock against what could have been an unequivocally exceptional movie.

The scenes of grunting soldiers bursting into the air

traffic controller room, metaphorically shaking their fists at the sky as their

prey barely slips away, reminded me of the finale of Brazil. This is the

dream action ending that Jonathan Pryce imagines, the soldiers repelling down,

in his case to save him from torment. In actuality, Pryce's character Lowry has gone mad, and this faux-Hollywood silliness is the raving of a broken mind.

The scenes of grunting soldiers bursting into the air

traffic controller room, metaphorically shaking their fists at the sky as their

prey barely slips away, reminded me of the finale of Brazil. This is the

dream action ending that Jonathan Pryce imagines, the soldiers repelling down,

in his case to save him from torment. In actuality, Pryce's character Lowry has gone mad, and this faux-Hollywood silliness is the raving of a broken mind.

To see a fine film undercut so severely by this whizz-bang finale is at best disappointing, at worst a scathing rebuke of the film as a whole. This is the central shame, here, that something like Pearl Harbor drapes it core historical fact with miserable character pieces, while Argo allows fine moments of character interaction to be supplanted by histrionic moments of cacophony.

Luckily, we don't need to judge either film on its normative veracity, and Argo's brief ten minutes of head-shaking stupidity nowhere near compare to the abomination that much of Bay's film provides its hapless audience. Still, I left the screening of Argo shaking my head in disbelief at the silly ending, finding jarring those bits of Bay's touch that still seem to subconsciously infect Affleck's filmmaking.

Argo is a well grounded, well executed film for the most part, making these excesses all that more jarring. I would recommend fans of the film read the dry, matter-of-fact declassified narrative that Tony Mendez wrote up for the CIA. Granting that the man is a deceiver by profession, the matter-of-fact way that he tells his version of the tale is quite gripping in its own way, while remaining for the most part almost banal. On first read, you can see that there's the core of a good movie in the actual events, but you simply couldn't end your film with a set of well fed hostages mildly anxious in the waiting room of an airport, waiting an hour for mechanical problems to be overcome.

One can readily see by reading this account those moments that Affleck and his collaborators either ramped up or completely fabricated, substituting the banality of reality with the heart-racing excitement of big-budget filmmaking. These additions, for the most part, are critical for any of the success of the film. My issue isn't the divergence from some notional version of reality, it's that I think, particularly with the airport scene, that they just went too damn far.

Lying about events to create a better movie is perfectly acceptable; you just have to do it well in order to succeed. For much of the running time Argo is a lot of fun, filled with genuine tension and charismatic performances. When it oversteps its scope, when it tries too damn hard to ratchet things up just one more notch, it has a brief moment of total collapse.

Luckily, by that point the film has earned its right to be a little ridiculous. I'm left mildly disappointed about a good film slightly marred by some fatuous moments, rather than completely repulsed at the entire enterprise.

I wish for Affleck to soon be exorcised completely of the Bay virus, and hope that his next project proves to be nothing short of extraordinary from start to finish.