Hideo Nakata Talks FOREIGN FILMMAKERS' GUIDE TO HOLLYWOOD And More!

Our very great thanks go out today to Jason Gray - English teacher to the stars, film translator and Screen International's Japan correspondent - for the following interview with Hideo Nakata, director of J-horror smash hit Ringu and freshly released documentary Foreign Filmmakers' Guide To Hollywood. Gray had the chance to sit with Nakata and talk at length about the documentary project as well as gathering some bits on upcoming English language feature Chatroom, and was gracious enough to pass the results on to us here.

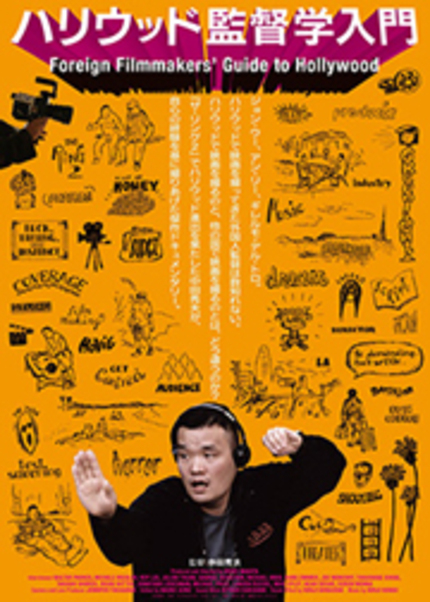

Hideo Nakata's latest film, a documentary entitled Foreign Filmmakers' Guide to Hollywood, opened at Tokyo's Theatre Image Forum in Shibuya, Tokyo on March 21. It will roll out in Osaka, Kyoto, Nagoya, Hiroshima and other cities in the coming months. A few weeks prior to its Tokyo bow I had the chance to sit down with Nakata at the offices of the film's distributor Bitters End. Nakata was suffering from kafunshô (cedar fever) at the time but graciously talked about the documentary and his other projects.

Jason Gray (JG): The last time I spoke to you was at the premiere of Kaidan. I liked that film and thought it deserved more attention and success. What are your feelings about it now?

Hideo Nakata (HN): Unfortunately there was no strong desire for an epic costume piece like that among young people -- they didn't care. It was titled Kaidan, which connotes a "scary ghost story" but it was half romance and half ghost story. But young people didn't appreciate the fact it was a mixture of those two elements. They just wanted to see an extreme, scary story with a title like that. Some of them might have felt cheated.

JG: But the advertising didn't sell it as pure horror. I hope there's still a chance for it to get some exposure overseas.

HN: I think we tried both Cannes and Venice but unfortunately they didn't select it.

JG: That's too bad. It could've been a nice link with Kobayashi's Kwaidan [related in Japanese title only] winning a prize back in 1965. Moving on to Foreign Filmmakers' Guide to Hollywood, I saw the film two weeks ago and enjoyed it. It was fun to watch and educational.

HN: Thank you.

JG: First, could you give me some practical information about the time period you shot the film and the equipment you used?

HN: It was shot roughly from September to November 2005. Of course we shot additional interviews later and the behind the scenes footage from the set of Kaidan in 2006, but most of the interviews were shot in the fall of 2005 in Los Angeles. That was the time I had decided to leave the project The Eye.

JG: You had made that decision before you started shooting?

HN: Well, I felt completely stuck and frustrated with the situation on The Eye. I felt it was better for me to take the job Kaidan back in Japan. Obviously I couldn't make the two movies simultaneously, but at the same time I was frustrated and couldn't allow myself to come back here with just one American movie in three years' time. I wanted to be more productive, so I thought why not just make a self-financed, inexpensive documentary with a small digital camera.

JG: A consumer camera?

HN: Yes. I and my assistant Jennifer Fukasawa [Nakata's assistant on The Ring Two and Kaidan] were the two sole crew members. I was the lighting director and she was the cameraperson and sound recordist. We went to a camera store called Sunny's and bought a semi-professional Sony model and what's called Spider lights, which are used for video interviews. And some sound recording equipment.

JG: How much planning was there as far as who you'd interview and whether it would be feature length?

HN: I didn't really know. I came up with the English title Foreign Filmmakers' Guide to Hollywood first. As you can see on the Japanese poster, there are names like John Woo, Ang Lee and Guillermo del Toro. Jennifer and I worked on the interviewee list. We tried to figure out how to approach them. Originally I thought it would be interesting to shoot interviews with these people. If they agreed this film would've been much more objective, even with me included. These are foreign directors who have their own issues with Hollywood. On second thought, because the idea began with my frustration I wanted to be faithful to that and use this negative feeling to change it into something positive.

JG: Do you feel it was a worthwhile pursuit?

HN: I hope so.

JG: The film is divided into three chapters – "Green Light", "Coverage" and "Test Screenings" – because you say these three are what basically separates Hollywood from other film industries around the world. Did those things change how you shot films when you came back to Japan, with Kaidan and L: Change the World for instance?

HN: Partially. With Kaidan, I shot coverage – the way I would for a Hollywood movie – for two sequences. The love scene between the two main characters and the action sequence toward the climax. With L, the sequence in the Thai village was shot in the way a Hollywood movie would be. My experience in Hollywood contributed in those cases, but I didn't want to change my style completely because with Japanese filmmaking I can act like a king. I can shoot the bits and pieces I want.

JG: I suppose in-camera editing scares Hollywood producers.

HN: Yes. But that's how I had been educated as a director. I used to be an AD and worked very closely with some master directors, and they never ever shot coverage. It's an interesting difference between America and Japan. It's not just about shooting. In Japan people might believe less is more or that directors can decide what can be thrown away, even before filming.

JG: And you have final cut here.

HN: No. Even with Ring or Kaidan, Takashige Ichise has the final cut but at the same time he'd never overrule. Sometimes we would argue like hell, but he's never said to me "Hideo, leave the editing room. I'll edit it myself." If I insist on the way to edit a scene, he will listen and we try to find the best solution without compromising.

JG: How about in Hollywood?

HN: Well, first of all Walter Parkes [producer of The Ring Two] never said to me "Hideo, your ideas suck. Stay home and relax." But that actually does happen in Hollywood. I know examples that were close to me. In Japan it can happen in theory, but as far as I know it's a very rare situation.

JG: My impression when I watched this documentary was that you were trying to work out in your mind what experience you had gone through in the previous two or three years.

HN: Yes, but at the same time I felt like I knew what I had gone through but that it was all from my subjective point of view, from my collaboration with Walter to how frustrated I became with the situation on The Eye. It was very subjective, which is why I wanted to get other people's viewpoints. Joe Menosky, for example. I thought as a screenwriter Joe would've talked about the same type of frustration, because he was basically replaced. But in the documentary he said if the replacement of a writer is a positive change, he could not say it's wrong. I was smiling but was also shocked at how easily he could accept the fact that even a director or writer can be disposable.

JG: You spoke to Hollywood figures such as Roy Lee, Walter Parkes, your agent Julien Thuan, producer Michele Weisler etc. but you also interview your contemporaries and collaborators such as Takashi Shimizu and Ichise. Was it important for you to hear their opinions as fellow Japanese people working in Hollywood?

HN: Yes, we share a similar but different experience. For example, I worked in the Hollywood studio system whereas they had a very strong ally.

JG: Sam Raimi?

HN: Right. We wanted to interview him, too, but it didn't work out. I can safely say that I am the first Japanese director who's experienced a true Hollywood studio system shoot, which is a unique experience. Half of it is suffering and frustration, but it also gave me a toughness.

JG: I think you must be the first person to make a documentary like this, too.

HN: (laughs) I don't know.

JG: Aside from the interviews and business talk I enjoyed how you showed your daily life, including your house and where you lived. I suppose for filmmakers here it must look fairly luxurious. Now that you're back, how do you feel about that aspect of life there?

HN: My intention for that section was...Fortunately or unfortunately we couldn't afford to use film clips of The Ring Two, even the behind the scenes stuff. In theory I could've asked DreamWorks but it would've been expensive. I wanted to give the audience some breathing room. Without those scenes it would've just been talking heads. When you say "I made a studio movie in Hollywood," of course people in Japan, or anywhere, would think that it's a luxurious, wonderful lifestyle. But as I mention in the film it can be very boring. At first I was staying at a hotel in Santa Monica. It was such a boring two-month summer period because I didn't drive and MGM asked me to stay longer and longer. When I was first called, they said one week, which became two, three, five and on. I ate every dish on the hotel menu.

JG: Were you writing at that time?

HN: No, there was a project called True Believers and MGM wanted to set up lots of meetings with actors for them to decide whether it would be green-lit. Life in L.A. can be boring if you don't have a car and unlike cities such as New York you cannot easily go to see classic movies or plays. My "luxurious" time was when my masseur would visit.

JG: I was going to ask why you decided to show that in the film [a sketch of the masseur is part of the poster's collage]

HN: I wanted to faithfully show my personal life. I did walk to the supermarket every day, because I didn't drive, fifteen minutes there and back. Yes, it was staged but also real. With this masseur from Israel...I wouldn't call him a friend (laughs) but he came to my place very regularly and advised me about my diet and knew how frustrated I was just by touching my back. At one point I became sleepless and my uric acid level became high. By touching and pushing my body he understood those problems and gave me very concrete advice – I owe him. When he treated me the first time he used Chinese heated glass suction cups on my back. My blood was almost black.

JG: The darker the blood the worse, right?

HN: Yes. But after a year and a half of treatment the colour became much lighter. And there's the scene of me walking up Runyon canyon and looking at the Hollywood sign.

JG: That's a great shot. Is that a metaphor for your challenges there?

HN: Yes and no, because I did actually do that run once a week, but stretching with the sign in the background was staged.

JG: You talk about the balance between commercialism and auteurism. How has that changed after this experience?

HN: I think Hollywood filmmaking is very faithful to the nature of commercial production. Without the approval of the audience we can't continue making movies. It's a miniature of capitalism. You need enough capital to continuously produce movies. I still cannot deny what I said to Shimizu-san in the movie – that in Hollywood I felt like I was making a car rather than a film. An industrial product. Filmmaking is that in a way. It should be saleable. Fortunately or unfortunately it's increasingly becoming commercialized in Japan. Budgets have gone up, at least for the movies I did after I came back.

JG: And more investors having a say about how the film should be?

HN: Fortunately those Japanese financiers didn't try to have a creative say.

JG: Not when you're the director.

HN: With Kaidan Taka kind of protected me. Now the era of "J-horror" is gone and I have to say I'm not a maniac about horror filmmaking so I should take this opportunity to move on. Quite interestingly, a British film producer approached me about Chatroom.

JG: How did you become involved with the project?

HN: When Jen Fukasawa and I presented another original project at the Hong Kong film market—

JG: Gensenkan? I wrote about it for my magazine.

HN: Oh, thank you. There we met a British sales agent called WestEnd Films and Jenny recommended me to Alison Owen, the producer of Chatroom. After Hong Kong, Alison sent me the script and I went to London. From there, Enda Walsh and I have been collaborating to revise it and now it's time for Film Four to decide to green light it.

JG: Again with the green light!

HN: I heard 75%-80% of the money is in place but they have to decide the UK, French and Italian distributors. Pre-sales in Berlin [the European Film Market] went well but the UK distributors mentioned that they have some issues with specific scenes in the script.

JG: Is Chatroom a return more to the style of Chaos?

HN: Well, there are thriller elements but it's about internet chatrooms, which are not that popular anymore but teenagers would access websites where they could talk about anything – mainly about their frustrations with family or modern society.

JG: And this was originally a play?

HN: Yes. Enda Walsh himself adapted it into a screenplay.

JG: He's known as a strong writer – he wrote Hunger.

HN: Right. It deals with a very dark reality, especially how young people's feelings of negative feelings of anxiety, hatred and anger can become amplified. A depressed boy can become even more depressed through this type of internet communication. It can reach extremes of killings or suicide. It's very disturbing in a way.

JG: Is there a production schedule in place?

HN: We are hoping to shoot very soon, in May or June. We have five main teenaged British actors already cast.

JG: Thank you for your time today.

HN: Thank you.