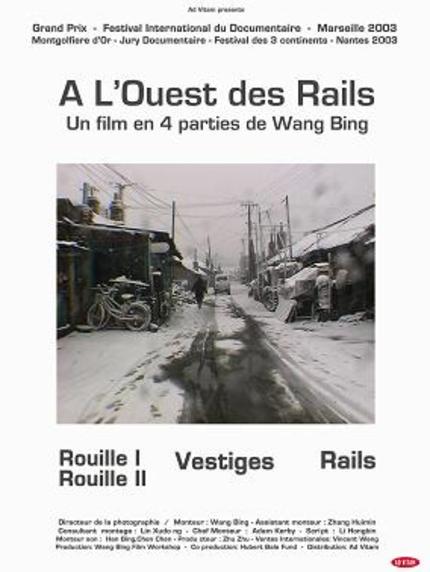

IFFR 2010 extra: Wang Bing's WEST OF THE TRACKS (Tie Xi Qu) DVD review

(Note: this is not a film that screened at Rotterdam this year, but given the festival helped release it seven years ago and publish what is currently the only DVD available with English subtitles, IFFR 2010 seemed a good excuse to finally upload a review. There's nothing on ScreenAnarchy to my knowledge about this seldom-seen work of utter genius, so I felt very strongly there deserved to be. Hopefully some of you will enjoy it.)

How do you write about something like this? (Other than 'at length'.) Wang Bing's West of the Tracks is unquestionably a masterpiece, yet it's one that - understandably - few people will ever see. It's the kind of staggering achievement completely beyond marks out of ten, yet at the same time this is a nine hour, three part documentary (yes, that's nine hours) about the decline of Chinese state-run heavy industry. Those currently running for the exits are certainly missing out, but one could argue both ways about how much.

So, to clarify; in 1999 Wang Bing, not long graduated from Beijing's Film Academy, arrived at the Tie Xi industrial district of Shenyang with little more than a tiny DV camera he didn't even own. Tie Xi (the name literally means 'west of the tracks') was at the time China's oldest and largest industrial centre, built by the Japanese in World War II, nationalised come the end of the war and subsequently taken over by the newly-founded Communist party.

Once Tie Xi was a beacon of socialist progress, but by the end of the millennium the machinery was falling apart (having gone without any significant upgrades for decades) and the administration was haemorrhaging funds day in, day out. Over the next three years, Wang Bing watched the district implode; factories going bankrupt, workers laid off, buildings torn down and the population relocated.

It took him a further two years to edit the footage he'd shot (more than three hundred hours of it) into three distinct parts; these cover the workers themselves, their homes and families, and the aftermath once the district was left little more than a ghost town. The finished documentary was aired on the festival circuit to widespread acclaim, but little subsequent exposure other than a limited DVD release in France, various one-off screenings in the US and Europe and the Rotterdam International Film Festival's (IFFR) DVD release (they partly funded and were first to champion the film) under their Tiger Releases label, which remains the only available edition with English subtitles.

1: RUST

Rust is the first part of the trilogy, where Wang Bing follows the metalworkers at the Tie Xi smelting plants, trailing them through their daily routines, their break times and their off hours. Right from the lengthy opening shots, with the camera mounted on the front of the goods train that runs through the district, the overarching sense of things winding down is established - the place is largely empty, too quiet and blanketed in snow.

Once inside, the factories are a ruin of rusted metal, peeling paintwork and obsolete technology clinging to life. Down on the floor, smoke, steam and loose particulates from the machinery billow across the camera, while the workers' breakrooms resemble every dank, crumbling portrait of the death of socialism ever put to film.

Wang captures every moment, from the mundane to the industrious. The workers laugh, argue, complain bitterly about their future prospects, spar drunkenly with each other or simply ramble about nothing much. They take little if any notice of Wang filming, beyond an occasional 'are you getting this?'. When one of the factory bosses lays out the scale of Tie Xi's debts, another moves to shut him up. 'No, it's okay. He's a friend', the first insists.

The director rarely speaks, and only off-camera. Snow, dirt and condensation settle on the lens. There's neither voiceover nor any music beyond the diegetic, and only brief explanation of who someone is or where we are. On that note, we see only wherever Wang Bing happened to be - with one camera there's no multiple simultaneous perspectives and little overt sense of a narrative beyond general chronological progression.

But then part of the genius of all three sections of the film is how, despite being about as objective as it is possible for a documentary to be, they can still prove frequently riveting. Even allowing for the temptation to romanticise such an alien existence the workers come across for the most part as genial, admirable and not a little humbling. Their worldview comprises a blend of wry fatalism, cynical bitterness and stoic camaraderie; what else can they do? Where else can they go? Tie Xi may be collapsing around them, but it's a job. It's their home.

One man sets out how well the factory ought to be running, all things being equal; another describes how the state let he and scores of other workers fail themselves (many of them theoretically qualified yet practically speaking, barely literate), but there's no malice in any of this, just weary black humour. Even when the owner turns up in person to announce fresh redundancies, someone jokes about seeing his chauffeur waiting with the engine running - 'I don't blame him' is the general consensus.

Wang also turns out to have an eye for the found image - presumably those three hundred hours contained a good deal of dross, but the final running time frequently proves visually stunning for all its technical limitations. Shot with a tiny handheld camera it may be, but much of West of the Tracks is honestly astonishing, the kind of imagery most filmmakers would happily kill for.

Wandering almost everywhere, before, during and after the collapse, the director captures some extraordinary moments; slow pans across the skyline; tracking shots from the goods trains; the factories, first crumbling hulks busy with motion, then later abandoned; demolition crews pulling the wreckage to pieces, and a worker picking through the deserted buildings for anything he can carry away.

2: REMNANTS

Remnants drags these death throes out to a stupefying degree (the trilogy grows notably darker as it moves on). The second instalment follows the population of Rainbow Road, one of the many housing estates dotted across Tie Xi. The workers' children are equally aware of what the future holds - Wang follows groups of young people as their parents come home jobless, followed by notices going up the estate is about to be demolished and all residents have to leave.

Watching the kids engage in perfectly ordinary teenage horseplay even as they acknowledge their world is on the verge of ending is heartbreaking enough but to subsequently see this happen goes beyond that. Again, there is little conventional structure here and neither overt melodrama nor consistent sense of closure. Wang never once imposes himself on events - sometimes he sees residents go, sometimes people he's followed for months simply disappear from the narrative without warning, with even their friends left wondering what happened.

Their houses are tiny, multiple generations crammed into a single room, and word swiftly goes out the prospective new homes are smaller still. Several die-hard squatters band together to try and coerce the government into offering a better deal. Wang stays with them as utilities are cut and winter descends yet again, watching while people huddle together for warmth, cooking by candlelight, reduced to melting snow for extra water.

3: RAILS

And yet Rails, the final part of the trilogy, is harder still thematically and emotionally. The shortest instalment (Rust totals four hours, Remnants three, Rails two) it follows the same goods train from which Wang took the very first long shots in the film. Even after Tie Xi has been left mostly wasteland the train is still running. The director trails the small, tightly-knit crew from some time near the end (they discuss the ongoing demolition seen in Remnants), riding in the cabin as they pass long, monotonous journeys round and round the district with amiable wisecracks and endless card games.

Two of the scavengers who now roam the district travel with the train; the wiry, one-eyed Old Du and his teenage son. Like the workers in Rust and Remnants walking off with their own tools, the crew are quite blasé about the two men claiming what little they can risk pilfering from the supply sheds. They may talk down to the old man at times, yet they're not shy about praising his dedication - 'Him and his son are the only people who know how to get things done around here any more', one of the crew remarks.

Old Du proves voluble enough once Wang focuses on him, happy to explain what led him to Tie Xi - he turns out to be one of the 'sent down generation' banished to work camps in the country at the tail-end of the 1960s, hopping between menial jobs before working security for the railroad ('All the police know me... otherwise I'd be arrested. I've got connections', he claims). He's clearly smart and resourceful for all his meagre existence, but a scavenger's guile can only accomplish so much. Hard-working or not, Old Du and his son are still squatters carrying off government property, and Rails' inevitable climax is utterly gruelling stuff, not least after spending so much time in the old man's company.

There's no agenda here, at least no more than standing witness implies. West of the Tracks doesn't outright condemn either capitalism or communism, it just notes - calmly, impassively - that progress carries a terrible cost for all those left behind, a haunting pragmatism that evokes fifth and sixth generation filmmakers' approaches to dramatising social upheaval and the plight of minorities or the dispossessed.

Is nine hours really necessary? The film could be cut, but Wang Bing's patient editing is a marvel - nothing stands out as superfluous and again, the individual sequences are phenomenal. There is a definite sense of working through a unified whole and a narrative arc, despite the slow, meandering progression and the way the film goes against conventional pacing in many respects. The problems come more from the sheer length of the thing - nine hours is far more than the vast majority of people (prospective viewers or not) could ever reasonably be expected to give up in one go.

Yet West of the Tracks is a masterpiece regardless. It's slow going, but it grips, in its own way; few if any features, narrative or documentary, have managed to immerse the viewer so completely in a vanished place and time, to say nothing of giving such an enterprise devastating contemporary relevance. Perhaps you know the things it's trying to say - again, Wang Bing's messages are fairly simple - but unless you've followed in the director's footsteps you haven't seen them presented like this, delivered with such jaw-dropping craft and devotion the film goes completely beyond any idea of grades, success or failure.

Any distributor would be taking a staggering risk picking it up, yet arguably the film would be best suited to a wider release on home video. While it is fantastically self-contained considering its length, it still works taken an hour or so at a time, almost as if it were shot for television. Bear in mind Wang Bing is obviously aware of the demands he's making on his audience; his most recent documentary The Journey of Crude Oil runs a colossal fourteen hours (he has two films that qualify for entry on Wikipedia's list of longest films ever released) and when screened at festivals it ran more as an art installation than an actual cinema viewing, with patrons free to wander in and out at will.

For anyone with the slightest interest in sitting through West of the Tracks who gets the chance it simply has to be seen. Of course it doesn't compel the viewer's attention for nine hours straight - that's arguably not physically possible. Does it elicit boredom? Very likely, if someone watches too much of it in one go, but that doesn't imply the film is boring. Given patience and commitment it is both every bit as captivating and as aesthetically outstanding as any top-tier blockbuster. Few people will ever see this, as it stands, yet more people definitely deserve to.

THE DVD

For those able to get their hands on it (the boxed set does not appear to be widely avilable online [unless someone can qualify that for me?]), the Tiger Releases DVD is about as good a presentation as the film could hope for. It seems to be taken from the same master as the French release - amusingly, the commercial DVD censors the frequent male nudity where the original festival screener left it intact - though there is one sequence of a crowd of workers silently watching a pornographic movie which remains untouched.

Still, given the limitations of the source footage (and the level of compression necessary even with four DVDs) the picture (in 4:3) is still clear, crisp enough and very watchable. Sound is adequate, though nothing happens to test anyone's speakers. Removable English subtitles are clear, concise and perfectly readable (Dutch is also available), though they appear to be taken from the festival screener, meaning they seem to be glossing over some amount of the dialogue.

The IFFR release also carries the interview with Wang Bing from the French DVD, confusingly included on the first disc (along with part 1 of Rails). This is a nineteen-minute clip which still has the original French title cards - plus Wang Bing speaks directly to camera for the whole clip, but a French narrator translates over the top of him. The interview also comes with English or Dutch subtitles, though while these are still perfectly well presented and readable they are unfortunately written rather poorly in several places.

At the time of writing Wang Bing is supposedly planning his first foray into feature film-making, Hometown, after an earlier experiment filming a narrative short (Brutality Factory) for the 2007 anthology The State of the World. His place in cinema history is practically assured as it is; given his keen artistic sensibilities and talent for dramatic, unconventional storytelling, should he try his hand at regular film-making it promises to be quite an event.