Echoes: How Young and Veteran Filmmakers in Pakistan Differ in Style and Storytelling

Pakistani cinema has been shaped by both veteran and emerging filmmakers, whose contrasting approaches to style and storytelling define the industry today. While pioneers worked within technical and structural constraints to establish cinematic traditions, the new generation is pushing boundaries with modern narratives and innovative techniques.

Veteran Pakistani filmmakers have shaped the nation's cinema through diverse genres. Some of the well-known names are Syed Noor, Shamim Ara, Sangeeta, Pervez Malik, Riaz Shahid, and many more. There was a time when their films not only dominated popular culture but also reflected the social and cultural sensibilities of their respective eras.

The films produced particularly from the 1960s to the 1990s used limited resources, however, relying on older camera equipment, which often forced the recycling of the same equipment for both black-and-white and color projects. The films mainly prioritized dramatic, song-heavy content over technical perfection, as the filmmakers had to work under tight budgets.

Films were plagued by overacting, repetitive plots, lack of trained crews and specialists, directors adopting a "do it yourself" (DIY) approach, and dependence on local studios that had their own constraints, scarcity of modern themes that could have appealed to modern audience and relying more on stereotypical plots with revenge sagas, all of which hampered the overall production quality.

Lollywood's decline was still inevitable due to several reasons. Infamously low-quality production and over-reliance on the same actors caused ample monotony. Whereas during this time, Bollywood embraced higher production values, adding to the preferences of Pakistani audiences for Indian films. Pakistani cinemas showed Indian films all through the year.

For the most part, Pakistani filmmakers of that era tended to overlook the audience's gradual shift toward global modernity and their growing acceptance of complex narratives from across the world. Thus, a continued production of subpar movies with storylines only centered on rural feudal communities became a drag.

Following the 2007 breakthrough Khuda Kay Liye, the revival of Pakistani cinema was solidified by critical and commercial hits tackling social issues, action, and romance. Key films included Bol (2011), Waar (2013), Dukhtar (2014), Manto (2014), Ho Mann Jahan (2015), Moor (2015), Verna (2017), Cake (2018), Laal Kabooter (2019), and the record-breaking The Legend of Maula Jatt (2022).

A new generation of filmmakers is redefining the craft with socially relevant and globally inspired narratives. High-definition shooting, guided by skilled cinematographers and DOPs, has become standard practice, while storytelling now places stronger emphasis on themes that resonate with today's audiences. Meticulous attention to narrative pacing is evident in the current wave of films, which tackle subjects such as education, child labour, civic responsibility through voting, and Pakistan's deep-rooted passion for cricket -- marking a noticeable and meaningful shift in cinematic sensibilities.

It also reflects on what kind of content the younger cinemagoers of Pakistan want to see. A research study showed that younger generations do not deem dance, songs, sound, and star power as the most important elements of a film now. Unlike the older audiences, younger generations have different perceptions regarding stories, themes, and dialogues, making them stronger and overpowering elements of the films for rising filmmakers now.

I wondered why romantic comedies are still gaining promising receptions in Pakistani cinemas? Possibly, this is due to their Eid release schedules, whereas the general belief that youth does not welcome realistic social dramas and intense social issues is now shunned. Such films offer great production value with impressive content, such as Bol (gender, religion), Dukhtar (child marriage), Verna (sexual assault), and many other similar titles.

2012's Saving Face was another fresh breath of air for Pakistani cinema, where a short documentary on how women victims of Pakistan survived acid attacks, directed by Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, won an Oscar. That being said, it might not have been possible without international collaborations at that time due to the dearth of resources.

Asian and European filmmakers came together for this new dawn of Pakistani cinema. Saving Face was co-directed by American filmmaker Daniel Junge, while another film, Seedlings/Lamha (2012), which went on to win numerous international awards, was co-produced by Meher Jaffri and an Australian TV professional, Summer Nicks.

There have been criticisms of their filmmaking process. Veteran filmmaker Salman Peerzada, for example, has who urged younger filmmakers "to understand the business of film and come out of the TV style of filming," as cited by Dawn News. I disagree, as it is this style of filmmaking that has set the young Pakistani filmmakers apart.

Salman Peerzada did assert that young filmmakers should come together, form unions, and support each other, which reiterates the evident lack of Lollywood's infrastructure, absence of funding, and strict cultural and social bans from the censorship board, points I explored in my previous article on why making a good Pakistani film remains so difficult.

New filmmakers helped in the rebirth of Pakistani cinema with, surprisingly, little experience in feature films. Bilal Lashari (Waar and The Legend of Maula Jatt) and Jami (Moor) were previously known for making music videos. Similarly, Kamal Khan directed critically acclaimed music videos before making his debut feature film Laal Kabooter, and worked in the visual department of Coke Studio.

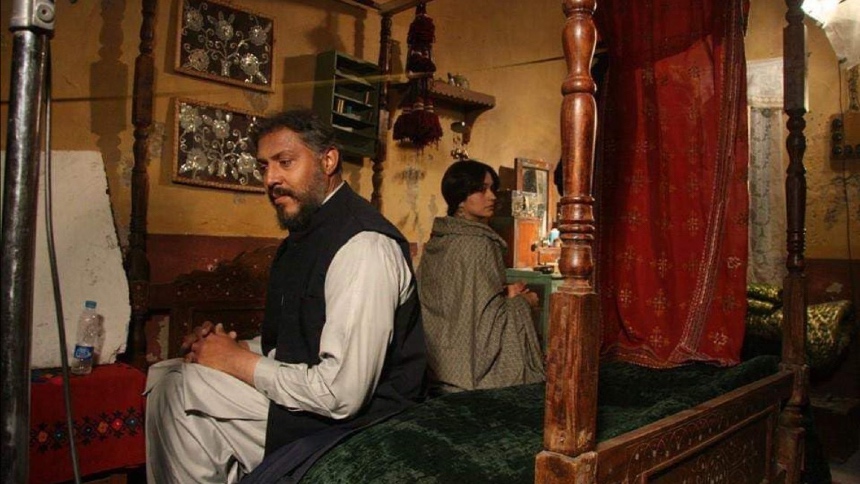

It should be noted that new filmmakers also belong to this generation of moviegoers who have grown intelligent by watching international content. Their aesthetics match that of Bollywood and Hollywood, but sadly, some of the exceptionally good production and high-value content remain with no spotlight due to weak marketing. For instance, Pakistan's official selection for Oscars, Moor (pictured at the top), was praised for its phenomenal cinematography but was overlooked by the mainstream audience as the film only managed to earn Rs 18.5 million at the box office against a budget of approximately Rs 50 million.

Younger filmmakers have come a long way, evolving from an era of scant funds and limited equipment to establishing a professional and resourceful space of their own. Departing from the methods of earlier filmmakers, their films now boast an incredible value in sound and post-production departments, marking an essential phase of resurgence and highlighting how the new generation's style and approach to filmmaking have redefined Pakistani cinema for the 21st century.

Echoes is an opinion column on film and television from the perspective of a writer based in Pakistan.