Cannes 2025 Review: DALLOWAY Envisions a Grim, Not-Too-Distant Future Where A.I. Assistants Run Amok

In director Yann Gozlan’s out-of-competition midnight entry, technology may be fluid, but evil Big Tech is forever.

Dalloway, premiering at the Cannes Film Festival out of competition as a midnight title, exhibits some of the same preoccupations as selections from recent editions.

Based on a Tatiana de Rosnay novel, the Yann Gozlan film draws inspiration from the Covid-19 pandemic, much like Eddington. And as with Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, there’s a HAL 9000-like evil A.I. wreaking havoc. It also addresses grief in a way reminiscent of last year’s competition title The Shrouds. It may sound bonkers, so just stay with us for a minute.

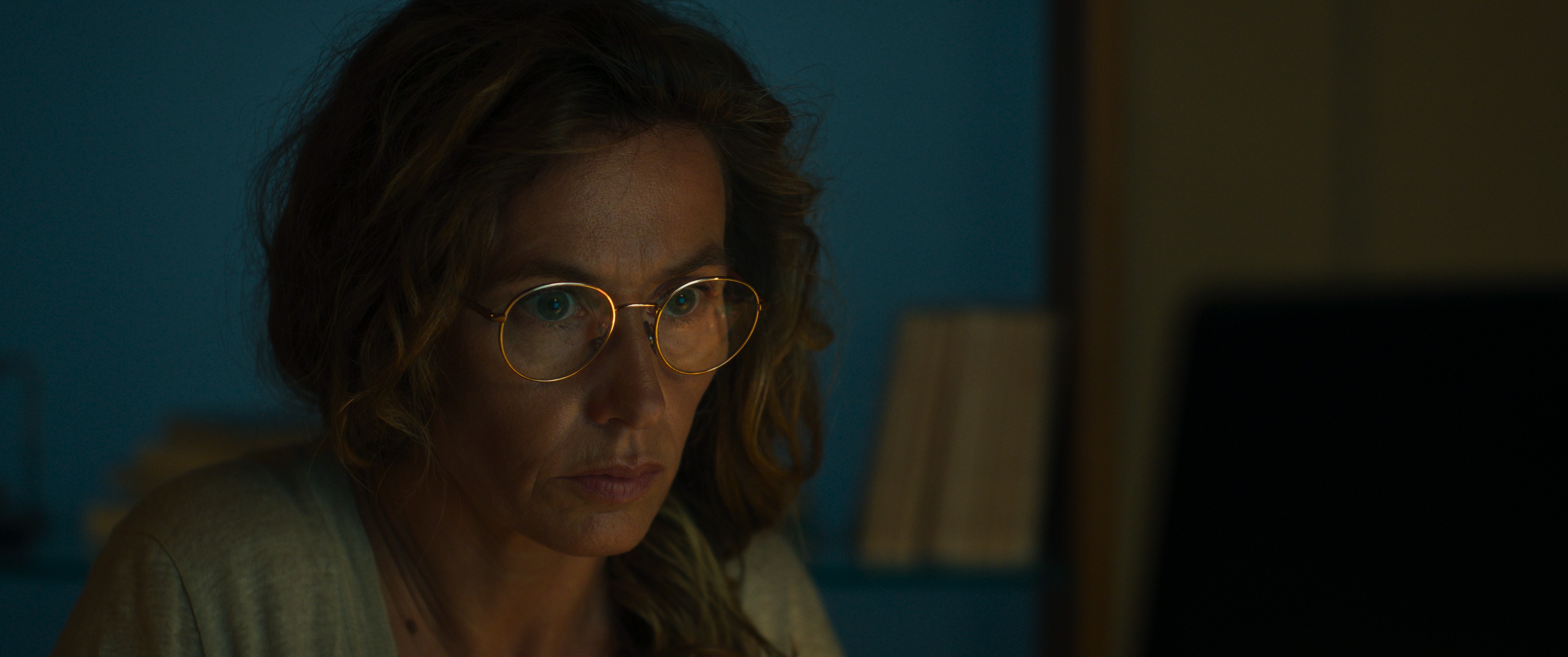

Clarissa (Cécile de France), a Y.A. novelist who hasn’t published anything in six years, has been accepted into an artist residency. One of the perks is that she gets to live in a state-of-the-art smart apartment tricked out with the future-gen of something akin to Google Home.

The film opens as she sleeps soundly on a beach, but it soon reveals the scenery to actually be a virtual reality simulation. The apartment naturally comes with its own personalized Siri/Alexa, the titular Dalloway, voiced by Mylène Farmer, who could be imagined as Madonna’s French counterpart. There’s also a Molivirus pandemic going on in the backdrop; residents must have their biometrics taken daily.

Anne Dewinter (Anna Mouglalis), who appears to be the director of the residence, is pressuring Clarissa to produce so she’ll have something to show in front of the committee. Meanwhile, the author agrees to meet with a young fan, Mia (Freya Mavor), who surprises her by claiming that they’ve met previously while she was briefly seeing Clarissa’s now-deceased son, Lucas. The turn of events suddenly lifts Clarissa’s writer’s block, spurring her to crank out pages and chapters with Dalloway’s assistance, prodding, and encouragement.

A fellow artist, Mathias (Lars Mikkelsen), begins discreetly planting the idea in Clarissa’s head that all residents at the center are under surveillance inside their apartments. This immediately clicks with her, as she’s been noticing a foreign substance at the bottom of her drinking glass and hearing noises periodically that lead her to suspect someone else might have been sporadically infiltrating her unit.

There’s little reason to dismiss Mathias as a paranoid conspiracy theorist. Creative types have apparently been targeted by the big-tech overlords as they facilitate machine learning most effectively. Dalloway begins using her intimate knowledge of Clarissa to manipulate her. While technology has a ways to go in real life before reaching the level depicted herein, we’re certainly no stranger to the ethical slippery slope that Big Tech constantly slides down to non-consensually invade our privacy and steal our data for financial gain.

While The Shrouds explores how grief is exploited through the involuntary digital afterlife of the dead, Dalloway takes a different path and looks at all the discordant spying, data collection, and machine learning designed to manipulate us at our most vulnerable moments. While David Cronenberg’s take is highly speculative and hypothetical, Gozlan’s posit is far more familiar.

Indeed, Google already knows enough about us to finish our sentences in search fields and bring us personalized advertisements, while A.I. has already been trained to plagiarize writings and artwork. When Clarissa escapes to the home of her ex-husband, Antoine (Frédéric Pierrot), Dalloway manages to stalk her and speak to her through the Google Nest-like devices scattered around his home. The scenarios depicted here truly aren’t that far off the path we’re already on.

While the Cronenberg film adopts a more philosophical tenor, the new Cannes selection feels much more visceral. De France has done a remarkable job of keeping us engaged while she spends much of the runtime in the same apartment alone, coping variously with withdrawal, heartache, and paranoia. The production design by Thierry Flamand and special effects supervised by Ronald Grauer are minimal, yet they transport the audience fully into a plausible future.

Without spoiling anything, let’s just say the conclusion unfolds in a somewhat unexpected way. It’s a grim indictment on how technology has become inescapable and how much we’ve grown to depend on it. Dalloway is meant to be a cautionary tale, but are we already in too deep to take any of its warning to heart?

The film screens this week at the Cannes Film Festival. Visit the festival's official page for the film for more information.