SING SING Review: Colman Domingo Leads Dynamite Cast in Stirring Prison Drama

Located just 30 miles from New York City on the Hudson River, the Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a 200-year-old maximum security prison, incarcerates what the criminal (in)justice system considers the worst of the worst, repeat, violent offenders serving decades-long sentences.

The men sentenced to Sing Sing are rarely if ever, seen as worthy of rehabilitation, let alone capable of rehabilitation and rejoining society one day. They were — and mostly still are — out of sight and out of mind where, to most, they belong.

Something changed, however, when Katherine Vockins founded the RTA (Rehabilitation Through the Arts) program at Sing Sing prison in 1996. As the name implies, the program allows long-term inmates to find creative expression through the arts (performing, dancing, writing), in turn creating a foundation for not just self-reflection, but self-healing and eventually, self-actualization (or rather a newer, better, more stable form of self).

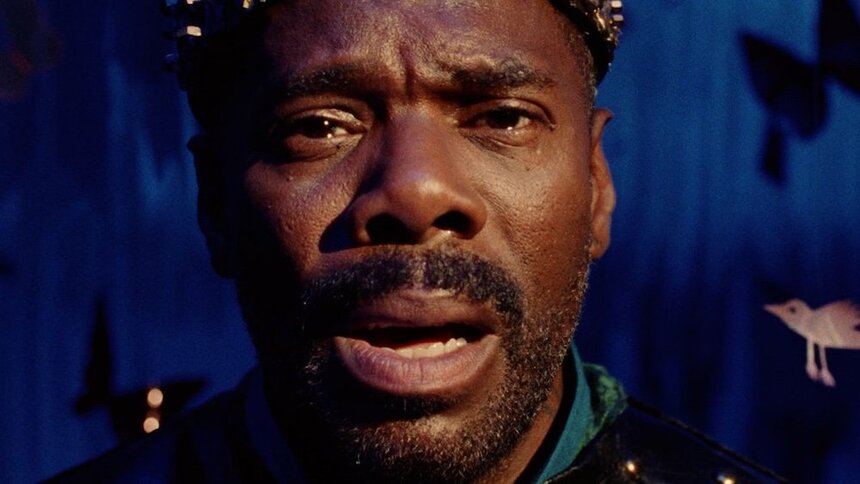

That background serves as a backdrop, sometimes literally, often metaphorically, for Sing Sing, Greg Kwedar’s multi-layered, empathetic exploration of the RTA and its impact on long-term prison inmates, centering its major storyline on award-winning actor-producer Colman Domingo’s character, John “Divine G” Whitfield, the de facto leader of Sing Sing’s RTA program. Under the guidance of Brent Buell (Paul Raci), the RTA’s director, the inmates — performers primarily drawn from formerly incarcerated persons— put on an entirely new performance every six months or so, often falling back on the classics (i.e., Shakespeare).

Like Whitfield and Buell, the third most important “character,” Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin, is based on a real-life individual/counterpart. Maclin plays a fictionalized version of himself, a streetwise, street-tough inmate with a big, extroverted personality and a desire to join the RTA program. When asked, Maclin can’t say exactly why he wants to join, only that he does, an answer that perplexes Whitfield’s right-hand man and best friend, Mike Mike (Sean San José).

While Whitfield initially sees nothing but positives in Maclin joining the troupe, he soon starts to second-guess himself. Maclin repeatedly challenges Whitfield’s authority within the group, successfully lobbying for a genre mash-up. Whitfield unsuccessfully attempts to convince the group to stage an adaptation of one of his plays, but Maclin wins the day, arguing instead for something light or lighter, something to simultaneously divert, distract, and entertain the inmates who make up the RTA’s literally captive audience.

When Buell returns after a weekend with a thick wad of paper in hand, it’s practically a certainty the play, Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code, a genre mashup involving Egyptian mummies, Old West cowboys, Shakespeare (again), and Freddy Krueger (among others), will see the lights of the stage located on prison grounds. Only practice, practice, and more practice (the oft-repeated phrase to “trust the process”), however, will get them where they need to properly put on a successful play.

As friction grows between the two men, understandable in part from shifting power dynamics, divergent personalities, and interests, the troupe remarkably doesn’t take sides, but instead reacts passively, allowing the two men to work out their differences, overcome their biases, and prejudices, and potentially form a stronger, more permanent bond than either man thought possible when they first met in a prison yard.

Besides the “let’s put on a play” throughline, Sing Sing mixes in a few, sometimes conflicting story elements, specifically Whitfield’s upcoming clemency hearing, Maclin’s later parole hearing, and the sudden, unexpected departure of a key member of the troupe, pushing at least one character to a self-described “breaking point.” (Every inmate, we’re told, has one; it’s just a matter of where and when they encounter their own.)

Not every story element works, some end in switchbacks, some in cul-de-sacs, and others feel only half-realized or under-developed. Sing Sing also “ends” more than once. And yet, a narrative speed bump here or there ultimately has little impact on Sing Sing’s stirring emotional throughline, of men, all long thought incapable of redemption, let alone rehabilitation, finding both through the performing arts themselves and the bonds the performing arts can create under seemingly impossible conditions.

Sing Sing opens theatrically in limited release today (Friday, July 12), via A24 Films, and expands nationally on Friday, August 2.