Blu-ray Review: Criterion Takes Us to Pit of ONIBABA

In fields of tall dry grass lies a pit just deep enough that escape is impossible. Not that any who fall in would think of escape, since they are already dead (or close enough) by the time they land with a dull thud at the bottom. How many men lie in this deep, we do not know. A few? Dozens? Their murderers don't keep track, they only know how much money can be made from the possessions of the corpse. Meanwhile, their anger and lust will drive these criminals apart soon enough.

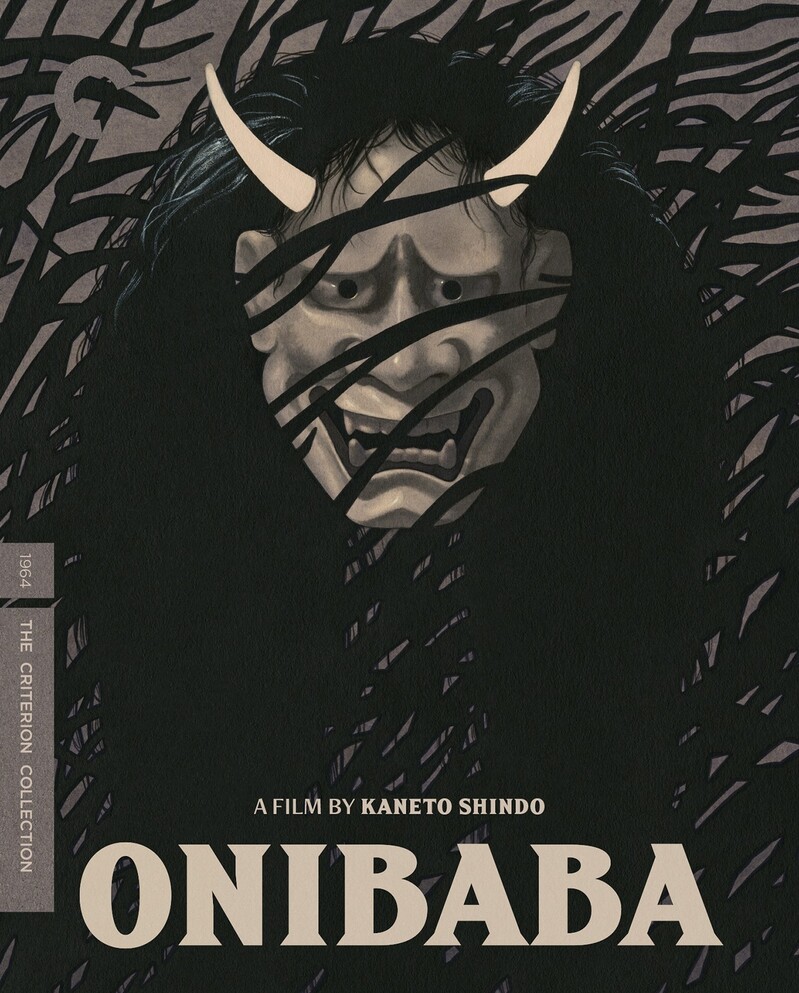

Criminals? Or Survivors? That's one of many questions asked in Shindô Kaneto's classic Onibaba. A tale of lust and murder, isolation and madness, Criterion has issued a new blu-ray edition, with the usual outstanding special features, including a fine restoration, interviews, extras, and essays. But even if it was just the film, it would be worth it. A terrifying tale of two women, the man who comes between them, and the desperation of their circumstances in a time of war.

15th century Japan was in a near constant state of war, so much that many people, mostly peasants, were left isolated and alone, with only their wits and whatever tools were on hand to survive. With men constantly going to war and often dying there, women were left to fend for themselves. In one corner of the country, within fields of tall grass, rivers and marshes, Older Woman (Otowa Nobuko) and her daughter-in-law Younger Woman (Yoshimura Jitsuko) do just that: only they fend for themselves by killing any stray samurai or traveller who crosses their path. They strip these men of their clothes, weapons, and goods, and dump their bodies in a hidden pit. They then sell these to the local black marketer. The sell the goods to buy what meagre food they can, try to sleep in their tiny hut in the heat, and wait.

Then their neighbour Hachi (Sato Kei) returns, claiming the son/husband has died, and pretty soon Hachi is quite openly lusting after Hachi. Tired of being alone, Younger Woman returns his lustful advances; but Older Woman finds herself growing enraged with jealousy, which drives a wedge between the women, threatening their survival.

It is a desparate life, to be sure. Older Woman is full of resentment and anger at her predicament; Younger Woman is full of anger at her own life seemingly cut short. Desire for human connection - the bond of skin on skin that she should have had with her husband, has nowhere to go. She might at first thumb her nose at Hachi, but she soon finds herself as embroiled in passion as he is. They are bodies filled with an energy that has no outlet other than each other. They are as blinding as the sun, their bodies as wet as the grass is dry, and either apart or together, their spirits rebel against the confinement of the life handed to them, trapped in a seemingly futile existence. No wonder they cling to each other.

The story is based on an old folk tale, and no such tale is complete without a monster. As Older Woman's resentment grows, she finds herself hatching plans, using an old Samurai mask she takes from a recent victim. But what exactly is a monster, Shindô seems to be be asking? It's not the lust of the neighbour and the Younger Woman, whose desiure he treats as natural as the sun and air. Not is it necessarily the anger of the Older Woman, now left without her only companion, herself still young enough to feel desire, but left to rot alone.

There is a raging, discordant enery running in the veins of this film. The music by Hayashi Hiraku, almost an experimental jazz, that matches the writhing and thrusting of sex, the heat of the days and sweat of the nights. The low key lighting throws everything in stark light and shadow, and the seeming gentle breeze across the grass disguises what lies beneath, the beating heart of a dark and living haunting.

Special Features

Given the age of the film, the restoration is particularly impressive. Its loses of its black and while, low key lighting glory, still feels tangible, and you can also hear the reel running through the projector. The uncompressed monaural soundtrack means the sound still has its texture, and if you watch this with the lights out, you can almost imagine the sight and sound of the filmn as if you were in the cinema; the story's power is enhanced by this restoration that honours the film's original form while fixing any problems that have occured with the aging of the negative. If, like me, you can get enough of this film and want to watch it again a second night in a row, the commentary from Shindo, Sato, and Yoshimura is great fun. Given the decades between when they made the film and when this was recorded, it's wonderful to hear how much they remember, and the joy and respect they seem to have for each other and the work, then and now.

On the disc itself, there is another rare treat: on location footage shot by Sato. He has a Super 8 camera with him and would frequently bring it out when he wasn't in front of the main camera. It's a rare opportunity to get a real look behind the scenes, at the people who helo boom mics or sewed costumes or checked scripts, letting us see how film is truly a group effort. Given the lack of sound and the age of the film, it also makes it feel like a ghostly artifact.

The booklet has a version of the original Buddhist fable on which the film is based, translated by Higashitani Reina and Tohda Moto from the edition produced in 2003, as well as a statement by the director, also reprinted from that edition, The essay by writer and scholar Elena Lazic gives a detailed context to the film. It details the story''s context in the 15th century, how peasants, especially women like the main characters, were left with little choice in ways to survive, and the conditions of their lives. It also notes how the story is a commentary on the time in which it was made, the 1960s. LIke many other countries, Japan was in the midst of a societal, and sexual, revolution, with young people defying the confinement of heteronormative forms of living, with women at the front of a revolution that demanded more agency and autonomy in their personal lives.

Shindô's work has never been as well known to many cinephiles and even casual film fans, as the work of Ozu Yasujiro or Kurosawa Akira, and that really needs to be rectified. Onibaba is a stand-out in his oeuvre, and this excellent re-release of the classic work with the Criterion treatment should hopefully find a wider audience.

Onibaba

Director(s)

- Kaneto Shindô

Writer(s)

- Kaneto Shindô

Cast

- Nobuko Otowa

- Jitsuko Yoshimura

- Kei Satô

- Jûkichi Uno