Interview: Director Sato Shinsuke on Finding Hope in ALICE IN BORDERLAND

By the time LMD had last interviewed Director Sato Shinsuke at 2018's Japan Cuts film festival premiere of Bleach, he was already pre-producing his epic adaptation, Kingdom, and lining up his next project; an eight-part miniseries that would mark his first collaboration with Netflix Japan.

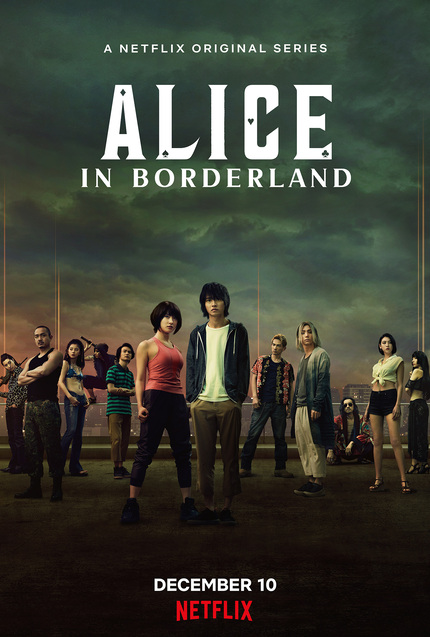

Based on a manga by Haro Aso, Alice in Borderland begins as the story of three aimless slacker pals, who suddenly find themselves in a Tokyo devoid of all humanity, except for a handful of strangers forced to play daily games of survival.

On a video call from Tokyo, Director Sato talked about pushing the envelope of violence and gore, the series’ uncanny parallels with today’s pandemic realities, and the hope that can be found in its message.

The Lady Miz Diva: I have to start by asking about the amazing opening sequence of an utterly abandoned Shibuya Scramble Crossing. Other filmmakers have told me that you can’t really get permits to film there, or close it off. I understand there was movie magic used?

Sato Shinsuke: So, what we did was we built sets, and of course we augmented that with CGI extensions. The key was to figure out which part to actually build and which to CGI? So, what we did was actually create something of a video storyboard, if you will.

My assistant director and I went to the intersection, and my A.D. was playing the main character, and when the light turned red, we kind of ran out, like a tiny indie film, and we actually did that to figure out which parts to actually build and which parts to CGI.

LMD: So, your A.D. got hazard pay?

SS: {Laughs} Yes! Actually, in that intersection there are a lot of people filming; YouTubers, Instagrammers, and tourists in general, and police don’t seem to bother them. It’s when an actual film crew goes in with a big film camera, they try to interfere, but if it’s ordinary people, they don’t. So, I was using a very small camera.

LMD: I recall from our previous conversations that you are a big manga fan. Was ALICE IN BORDERLAND a manga you liked, or was it presented to you?

SS: So, actually this all started four years ago. Netflix Japan opened its offices about five years ago, so it was right after it opened that the producers at Netflix were already looking for a project like this and found this material.

They were looking for something that would, of course, work for Japanese viewers. Although at the time, they had just started their services in Japan, so the subscriber numbers were still not that huge, but they were also looking for something that would work internationally, as well, and this is how they found the source material. I hadn’t actually known about the manga until they pitched it to me.

LMD: It feels like you’ve known it for years, that you’ve saturated yourself in it.

SS: Of course, I read the material and I loved it and thought it was great. It’s kind of difficult to explain my thinking at the beginning, because it was a very difficult manga source material to capture in terms of what to dramatise when turned into a series or a show or a film, but I knew that I was going to be able to maybe do something that has never been seen before. So, that made it really, really exciting, that’s what I remember. And once I decided, it became my bible.

So, I read it inside and out, trying to find the essence of what would make this material really fun. Of course, I would reinterpret that, and give it a rebirth, if you will, through my creative process. I love the material, and I can keep on talking about it because is so much talk about.

LMD: In terms of the visuals and production, the series looks like eight short feature films, as opposed to what one might expect from a television or streaming project. You mentioned that Netflix Japan was in its early stages when they approached you to direct ALICE IN BORDERLAND. Please tell us about collaborating with Netflix. Did you have freedom to do everything you wanted?

SS: When Netflix approached me -- usually, we have TV shows, “dramas,” as we call them here -- they are usually produced by TV broadcasters; they are more kind of episodic. But what Netflix asked me to do was to think of it, the eight episodes, as one very, very long film, and to try to maintain the tonality throughout. I immediately understood what they were talking about, because I do watch shows from abroad, and I have seen the recent tendencies of these shows, especially the dramas, that visually, I can very much identify with, as I am somebody who works in cinema. That was exactly what I wanted to do.

I have experience working with TV companies with other directors, different directors helming each episode. So, I’ve done that format before, but this time I decided to direct all episodes by myself, because I wanted to make it a long film. I knew we would actually film for five months. That’s quite a long time; I knew it was going to be a challenge, but I had experienced a five month long shoot shooting GANTZ parts one and two, back-to-back. So, I knew I could probably be able to do it, but I tried to really think of it as one big flow, rather than eight different parts. I approached it really as a film, even with the number of cameras I was using. Usually on my sets, I will use maybe one, sometimes two cameras only, and that’s what I did with this show. I didn’t do things thinking, ‘Okay, this is a TV show, so I have to do it this way.’

And with regard to my collaboration with Netflix, in terms of time limitations, there wasn’t that much of that. Sometimes, when you’re making films, especially Japanese films, you are asked to really consider the market for Japan, which can be very specific, but that didn’t happen with Netflix. It was much broader; they just told me, “Let’s make something that we feel that’s exciting, or you feel that is interesting, and that’s what we can share with the world.” That was exactly what I have been wanting to do, even before I had this offer.

Sometimes when you’re making a film, even if you are considering it going to different markets, if the film is primarily targeted for Japanese audiences, there are things that you have to take into consideration. But with this project, I was able to take away all of that, and truly focus on what I thought really interesting and exciting, because that, in turn, will be what the audience would want. That was Netflix’s attitude, as well. Everything went smoothly, and it was really, really a comfortable ride.

LMD: I’m glad you mentioned GANTZ in your last answer, because I thought the GANTZ films, or I AM A HERO was as violent as you were going to get onscreen. ALICE IN BORDERLAND is quite strong in terms of intensity and brutal visuals. Was there a connection between the freedom that you found working with Netflix and wanting to push the envelope in terms of violence or gore?

SS: So, Netflix has their own sort of rating when it comes to expression, including violence. The criteria is different from the Japanese film rating system and the MPAA. Netflix’s criteria is a little more flexible, so, if I wanted to do it, I was given that freedom. But I never wanted to do violence for the sake of violence; that’s not what I do. If it’s necessary to the storytelling, I would definitely insist on having that level of violence or gore.

Of course, what a person finds brutal will depend on the person’s sensibilities. But that aside, compared to I AM A HERO, which as you know is a zombie film, the expression of violence in that film was sometimes very cathartic. I feel that in this show, I don’t use it to that level. I wanted to be like a thorn that really gets you when you’re not paying attention, so you would kind of be like, ‘Wow!’ That was the way I was thinking I was going to use violence in this series.

LMD: I feel there is a growing director/actor collaborative growing between yourself and Mr. Yamazaki Kento, kind of like a manga adaptation Scorsese and De Niro. He has appeared in this series, in your last film, KINGDOM, and as I understand, will also be in your next film. Please tell me about your collaboration with Yamazaki-san, and what qualities he has as an actor that suit your visions so well?

SS: With Yamazaki-san, when he is in a work like this, which is slightly darker and full of desperation, he is the one can bring hope and hopefulness to the show or the film. He has that quality. He was kind of born with it, really; that kind of light, if you will, that hopefulness, that familiarity that makes you want to stay with the character.

And especially when you’re telling a story that may be sad, or may be hard or challenging, sometimes you don’t want to go ahead, or just want to erase everything; by him being in that story, playing a character, the audience wants to stay with him and stay with the story. He’s able to bring life to such characters, so I felt it was of great importance that he was part of a project like this.

LMD: Returning to those scenes of an empty Shibuya; it was very chilling to watch. As we know, Shibuya is considered the Times Square of Tokyo. Earlier this year, as we in New York went into lockdown because of Covid-19, people took many pictures of empty Times Square, the way Shibuya looks in your series.

Of course, ALICE IN BORDERLAND was planned and filmed long before, but has releasing it during the pandemic given you a different perspective or new meaning to the project?

SS: I’m not quite sure about the new meaning. I started this journey working on the story three years ago. Actually, when you look at the source material, the way that that the people arrive at the Borderland is through kind of a space/time tunnel; and they arrive at a dim expression of the city, if you will, and that’s how it began. But instead of the characters going to that place, I wanted them to have the people that are around them suddenly disappear, because I felt that to be more fearful, to be more horrific, especially in our modern society.

So, that’s what I wanted to do, and I really wanted to do that in that almost saturated, densely populated intersection in Shibuya. That’s an image I had from the get-go. It was going to take a lot of work and a lot of money, but the producers understood what I was trying to achieve, and that’s why we were able to do it.

And of course, simultaneously, the same sort of thing happened in Japan, in Shibuya, as well. But I feel like in the world before, when things were densely saturated, and everything was full to the max; living in that society, I think I subconsciously had this fear of that world suddenly breaking apart, and everything disappearing in one instance, very suddenly. Of course, I hadn’t thought that that was actually going to happen in reality, at all, but there was a sense within me that something was reaching a peak, a fever pitch, if you will.

But the show is about the characters finding hope in a desperate world, really struggling with a lot of things to find and choose how they’re going to live their life. I think that’s a reality that we are confronting now. So, it feels very strange; I feel very strange about that.

I think in filmmaking, you use your imagination fully in order to create, and I think that if things are not concrete in your mind, those vague feelings somehow manifest in your work. So, I think maybe it happened coincidentally, but at the same time, there was some kind of a necessity -- and this might be a strange word -- that this was going to manifest.

LMD: As we are on the edge of our seats by the end of episode eight, I’m guessing there must be plans in the works for season two?

SS: I hope there’s a season two! {Laughs} I was looking at some of the reaction online to the show on Twitter and social media. Right after the release, after the running time of the total of the show, there were tweets saying that they actually had seen the whole thing, and that they were looking forward to season two. That there has to be a season two. So, I’m really gratified and really happy, that everybody is hoping for another season.

LMD: It’s a law: You can’t bring in the blimps and leave everybody hanging.

SS: {Laughs}

LMD: What is next? I have read about KINGDOM 2

SS: Well, it’s already announced. Yes, KINGDOM 2. Covid has made us have to delay certain things. I’m really, really working on it, now.

LMD: Well, there’s another “2” film that I’m looking for news about. I think you might know what I mean…

SS: {Laughs} Probably BLEACH. {Laughs} Of course, that is what you first interviewed me for. We are talking about it, but of course, I have projects that I’m involved in that have to be done in order, but I am looking forward to it.

LMD: Director Sato, what would you like ALICE IN BORDERLAND to say to viewers around the world?

SS: Well, going in, I hope everybody sort of watches it with a blank slate, and starts watching it casually. I hope they are surprised. I hope they find certain things fearful. And I think if we’re living our ordinary lives, it’s sometimes hard to really feel what it is to live, or what we’re living for; or the experience of living, but I hope that is something you take away from watching the show.

We are, of course, living in this particular world right now, where strangely enough, streaming has become something that is more widely received, and I think a lot of people probably watching the show will link it to what is going on now in the real world, as well. It’s interesting, isn’t it, because watching it in this kind of darkish environment that we are thrust in, watching shows and films streaming gives us hope. And that is also the theme of the series; as well, so I hope that they take that away; what it means to live with hope

ALICE IN BORDERLAND is streaming only on Netflix

This interview is cross-posted on my own site, The Diva Review. Please enjoy additional content, including exclusive photos there.

This interview is cross-posted on my own site, The Diva Review. Please enjoy additional content, including exclusive photos there.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.