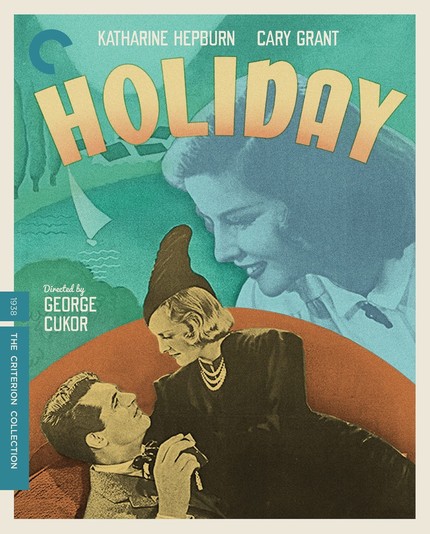

Blu-ray Review: George Cukor's HOLIDAY Is As Alive as Ever

The screwball genre may remember George Cukor most fondly for his Katherine Hepburne / Cary Grant vehicle, 1940’s The Philadelphia Story, which helped to rescue Kat from her cruel ‘box office poison’ tagging. But for my patronage, Cukor’s lesser-known, Holiday, released two years prior, resonates among the finest entries, not just of the Grant/Hepburn pairings, with which Bringing Up Baby also competes, but of the entire period.

It’s not that playwright Phillip Barry’s comedy of manners, Holiday (1928), is especially funny as much as it is charming as all hell, particularly when met with a worthy director. Take the hit broadway play’s two Hollywood adaptations: whereas the first version, directed by Edward H. Griffith as an early celluloid talkie in 1930, is dry and lifeless, Cukor’s Holiday (1938), a poignant lark told with spirit, takes a zestful aim at high society types with a reverence for riches.

The story begins shortly after Johnny Case returns home from Lake Placid where he’d recently spent his first-ever vacation. Orphaned at a young age, Case spent his life earning his way through school by any means necessary, taking on two jobs in order to afford the privilege of studying at the university intended for him by his deceased mother. Now at thirty-years-old and on the brink of earning a small fortune in stocks, Johnny has met Linda Seton, the young woman he’d like to marry and fast. What he doesn’t realize at the outset but is soon to find out is that his bride-to-be culls from one of the city’s most affluent families.

Likewise, the soon to be Mrs. Case doesn’t quite appreciate that her Johnny is what you might call a dreamer and one with a master plan. Once he succeeds at accumulating $20,000 hard-earned dollars, Johnny has a mind to enjoy his finite duration on this earth as a man whose ‘time is his own’; a societal dropout for as long as he can swing it. In Case’s words, “to find out who I am and what I am and what goes on and what about it. Now, while I'm young, and feel good all the time.” Though no one in the Seton dynasty can deny Case’s tenacity and work ethic, on the ‘independent thought’ front, Mr. Seton especially finds Johnny’s attitude “deliberately un-American.”

In literary terms, Johnny is ready to take an extended holiday, ‘Roughing It’ like Twain, hitting the 1930s version of Kerouac’s road, or taking Jarmusch’s Permanent Vacation, exercising Matthew McConaughey as David Wooderson’s concept of L-I-V-I-N’. In short, Case is a real free spirit; an oddity of the modernist generation and one immediately recognized as such by the black sheep of the prestigious Seton family, Julia’s sister Linda. “You do like him, don’t you?” Julia asks her sister Linda after first meeting Johnny. “She asks me if I like him”, Linda says to no one. “My dear girl, do you realize that life walked into this house this morning?”

Since there isn’t much in the way of extravagant situational comedy, the play and its two locationally thin thirties Hollywood adaptations relied largely on Phillip Barry’s endearing characters, both yearning for the same freedom from opposite backgrounds, and the contagious rapport of their forbidden romance. But in comparing Cukor’s 1938 version with Griffith’s early talkie rendition, you really come to appreciate just how crucial the role of the actor becomes in bringing life to words on a page. Unlike the wooden ensemble of Griffith’s makeup-caked cast of 1930, the chemistry between Cary Grant as Johnny Case and Kat Hepburn as sister Linda is the stuff of which silver screen magic is made - this cannot be understated.

Rounded out with some of the period’s finest supporting players - Jean Dixon and Edward Everett Horton as two wittily wise professors/spiritual guardians for Johnny, Doris Nolan as fiance Julia, and an especially bittersweet performance by Lew Ayres as the tragically drunken third Seaton sibling, brother Ned - Holiday is alive with feeling and holy foolishness, personified by some of Hollywood’s finest actors at the peak of their burgeoning stars.

The Criterion Collection, who has chosen Holiday for their first screwball entry of the 2020s, is wise to include both the 1930 and 1938 versions. The pairing enunciates not only the supremacy of the second cinematic telling but makes you appreciate just how good Kat and Cary really were. Replete with acrobatic prowess on delightful display throughout the film, the co-stars shine in a way that is incomparably winning.

Hepburn’s tenacious comedic timing transforms into gutting dramatic chops seamlessly while Grant explodes with an irresistible joie de vivre. When Kat as Linda tells sister Julia in reference to Cary as Johnny that “life walked into this house this morning”, the audience understands exactly what she means. To see the same line delivered in the 1930s version in reference to a dud of an actor (may he rest in peace) is to understand how empty words can be without the personality to back them up.

Criterion’s presentation of Cukor’s Holiday looks and sounds spectacular in its 4K restoration with uncompressed monaural sound. In addition to offering Edward H. Griffith’s Holiday of 1930, the supplemental offerings consist of a new and very enjoyable thirty-minute conversation between filmmaker and distributor Michael Schlesinger and film critic Michael Sragow, two rare audio excerpts from an American Film Institute oral history with director George Cukor, recorded in 1970 and ’71, and a costume photo gallery showcasing the satirically lavish clothes adorning the rich and fabulous in the eyes of Cukor and designer Robert Kalloch.

The package’s accompanying essay, penned by Slate film critic, Dana Stevens, who has also provided Criterion with wise words on Election, offers a rich backstory for both Hepburn and Grant, whose paths seemed destined to cross in this project. The role of Linda was of particular significance for Hepburn who first understudied for the role on Broadway, looking up to the play’s leading lady, Hope Williams, a real-life society debutante and swagger girl Hepburn refers to as, “the first fascinating personality from that period... which wasn’t really ready for her. She was a woman who blossomed with a little more than she was supposed to.”

What’s most astounding is to learn that Cukor would give Hepburn her first role in 1932’s Bill of Divorcement after watching her audition as a tribute to Hope Williams’ Linda with a scene from Holiday. Stevens sums up her much-appreciated history lesson commenting on the kismet of the film’s powerhouse collaboration and realization of the Grant/Hepburn/Cukor synergetic potential; “To watch Holiday is to see two great performers falling in love—not with each other’s real-life selves but with the work they were just beginning to realize they could do together.”

It is indeed one of Hollywood’s most fortunate triumvirates and one that benefited imperatively from the source material; both Barry’s socially flippant play as well as screenwriters, Donald Ogden Stewart and Sidney Buchman’s, astute cinematic melding to the extraordinary presences of both the circus-raised Cary Grant and the Linda-in-waiting Katherine Hepburn.

In 2020, Phillip Barry’s Johnny Case character, the ambitiously aimless should-be adult who refuses to cash in his lust for life for stability, thus sacrificing the ‘life’ Linda observed when he first walked through the door, is as, if not more, beautiful than ever thanks to the life that once walked through the doors of Cukor’s set. It is the life of divine talents wisely given room to breathe, relax, and thrive within the potential of a good script.

To watch the film today almost a hundred years after its initial inception is to see an ancient work still very much alive and burning with an ageless energy ever-ready to make you smile. Check it out.