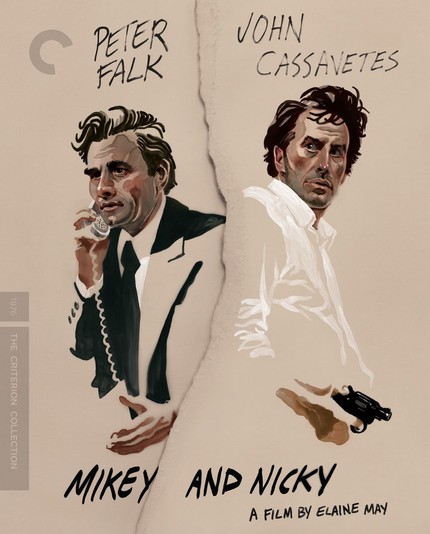

Blu-ray Review: Criterion Dissects MIKEY & NICKY

A lifelong friend is not an easy thing to come by, and the older we get, the more we can appreciate the rarity of such a relationship.

Peter Falk articulates this well in a 45-minute radio interview included in the new Criterion release of Elaine May’s 1976 masterpiece, Mikey & Nicky, in which he elaborates that, once you become a teenager, the window closes for acquiring these types of relationships, and if you were lucky enough to have recruited one at such an early life juncture, you’ll know something about the double-edged sword of lifelong familiarity. Once you grow up, like it or not, these are the people who will know exactly where you’re coming from, because they’re as etched in your DNA as you in theirs.

Mikey and Nicky are best friends from childhood. They were literally there for each other in that they participated in each other's early developmental stages. Nicky remembers Mikey’s brother who didn’t live past ten years of age. Mikey remembers Nicky’s mother, also of blessed and increasingly distant memory.

Now in their mid-40s, Mikey and Nicky have remained constants in each other’s lives, even if the years have offered a wide range of shifting relationship dynamics. It’s a friendship story that would be profoundly salient for the most mild-mannered of law-abiding characters, but May’s heroes are volatile blue collar mobsters who have inherited ideals of toxic masculinity from a long line of vile, misogynistic male role models before them.

As the film’s tagline warns, “don’t expect to like them”. And yet May does like them, or at least she isn’t quite as quick to demonize the type of men who made up her own family, as one might be tempted to do to her unlikely heroes. Rather than wholly dismissing this thankfully dying breed of confused men -- the man’s man -- and approaching the film as an indictment of these types of guys, by casting some very human friends of hers, Peter Falk and John Cassavetes, she’s able to examine the type of men she was raised by and alongside, with lovingly raised eyebrows.

As you’ll learn from the many interviews on the Criterion disc -- from Paramount distributor-turned-Elaine May producer Julian Schlossberg, film critics Richard Brody and Carrie Rickey, and actors Peter Falk and Joyce Van Patten (who plays Jan, Nicky’s emotionally abused wife) -- May was actually raised by a family, who participated in the bigger, more proverbial sense of the word, and Mikey & Nicky is basically a true story told to her by her brother about a cousin who was assigned to ‘off’ his best friend.

As The Sopranos taught, if a mobster is to be terminated, traditionally a trusted individual is given the unhappy job of escorting his pal to his unknowing demise. If you can’t trust your childhood best friend, who can you trust? This is the unfortunate situation in which Nicky finds himself at the beginning of the film. Having ripped off his boss, Cassavetes’ Nicky is beyond a nervous wreck. His number is up and he knows it. There’s only one person in the world to whom he can turn, and even in his mania, he understands the limits of this trust.

It’s both comical and actually quite sweet the way Falk’s Mikey looks after his vulnerably frenzied friend in hiding. So much so, that when the audience learns about 15 minutes into the film that Mikey does in fact aim to deliver Nicky to one of the great assassin characters ever depicted (played petilly by Ned Beatty), knowing nothing of their relationship beyond the charming rapport on display thus far, the audience hates him for his intentions.

The genius of the film, however, lies in the way Elaine May subverts every expectation she sets up, constantly penalizing the audience for judging her characters and their mysterious motivations too quickly. So while it’s immediately disappointing to realize that Mikey, as it turns out, is indeed the type of person who’d set up his best friend, by the end of the film, once their lifelong relationship is intricately peeled away bit by bit like an onion, the audience is left with a fully-rounded account of a gradual hate that could only exist off the heels of profound love.

Perhaps this is what makes May’s family-within-a-family mafia opus so very satisfying. As much as most wish they were, criminals are not above the intricacies of human relations, nor the emotional dependencies that genuine connections can stir. Thus, Mikey & Nicky, which in addition to being tickled by this, also deeply empathizes, is as raw and rich a film about family rivalry as you're likely to see.

To reiterate May’s tagline, you may not like them, but if -- thanks to some incredibly captivating performances that utilize everything Cassavetes (the actors’ director) had been working towards, and shot with similar independent grit championing spontaneity above all else -- you find yourself confused as to why you might actually love them, you'll get close to understanding what I suspect May was hoping to understand for herself.