Review: LOST CHILD, Mysteries of Pain in the Ozarks

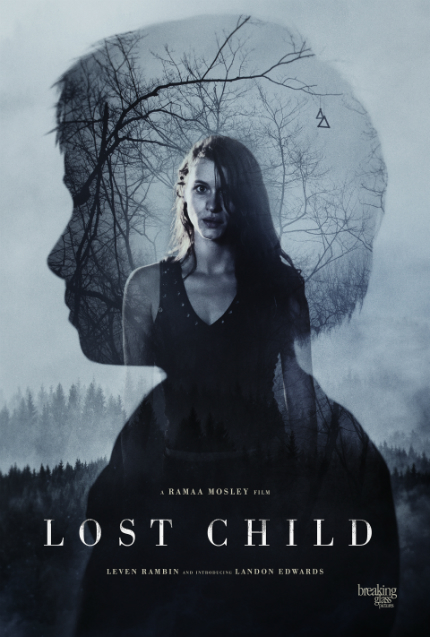

Leven Rambin stars as a military veteran who must come to terms with her past after she encounters a mysterious boy; Ramaa Mosly directed.

Known for the lighthearted comic fantasy The Brass Teapot, Ramaa Mosley (director and cowriter) and Tim Macy (cowriter) turn toward darker territory in Lost Child.

In his review of Mosley's debut feature, Kurt Halfyard noted: "Its earnest celebration of the cluelessness of the American Middle Class -- a cynicism-free faith that eventually they will do the right thing -- is endearing." The characters in Lost Child represent the flip side of that description; they are members of the struggling American Lower Class and they are cynical about nearly everything, even their faith.

After 15 years away, military veteran Fern (Leven Rambin) reluctantly returns home to the Ozark Mountains region in Arkansas when her father dies. She was long estranged from him, her mother is long out of the picture, and she has no burning desire to renew old acquaintances. Really, all she wants to do is reconnect with her younger brother, Billy, and get out of town.

Before she can do that, though, she must suffer the inquisitive nature of family friend Florine (Toni Chritton Johnson) and the buried passion of former boyfriend Mike (Jim Parrack). In her own private and guarded manner, she is also dealing with trauma from her military service, which has caused her to renounce guns and violence.

Then she encounters an unaccompanied boy in the woods near her family home. Cecil (Landon Edwards) accepts her wary invitation; he is quiet and polite, but refuses to identify himself or give any clues about his background or how he ended up fending for himself in the wild. In another film, this might be viewed as an entirely good thing: the child who helps the hero to realize that she can love again and become the mother she never had.

Instead, Cecil causes nothing but trouble for Fern. She calls upon social services to pick the kid up and learns that Mike is the sole local representative. Mike is revealed to be kind and caring in his work, and he (gently) pushes Fern to care for Cecil until more can be learned about him. What, for example, happened to his parents? How and why was he abandoned?

Cecil appears to suggest that otherworldly forces may be involved, but the film's tone and atmosphere never follow his suggestions. Rather than the supernatural, the focus remains on an empathetic drama of characters, their own, varied if unacknowledged imperfections, as well as their outright failures as human beings.

It might be misleading to describe Lost Child as a thriller; unlike studio melodramas, it never quickens its pace for no reason or deepens its mysteries in unexpected, artificial twists or turns. Yet its moments of intense, piercing drama certainly hit home in convincing fashion. Fern doesn't quite know what she needs, but she knows what she doesn't want. Until she figures out her own desires, she tends to push everything else away. The question becomes, can she ever come to terms with her past?

Rambin carries the picture effectively, without resorting to cliches. Parrack provides good support. Edwards is an unaffected young actor. Darin Moran's photography captures the actors and scenic backgrounds beautifully. Good ideas brew throughout Lost Child, leading to a satisfying conclusion.

The film will open in New York at Cinema Village and in Los Angeles at Laemmle Noho on Friday, September 14, via Breaking Glass Pictures. It will be available to watch on various Video On Demand platforms on Tuesday, September 18.