Blu-ray Review: THE FILMS OF NIKOLAUS GEYRHALTER Show us our Beautiful, Terrible World

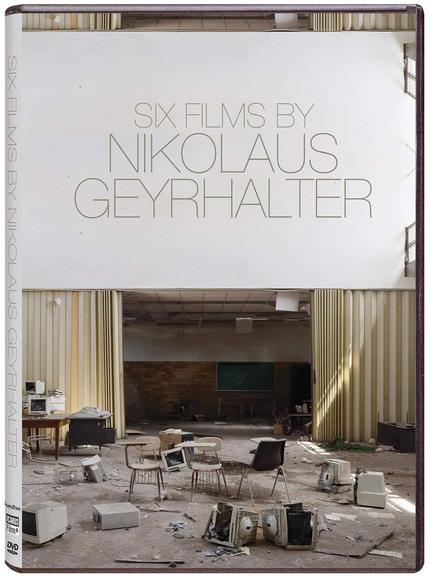

Icarus Films presents a stunning DVD collection of unique documentaries showing life on Earth.

Languid and without judgement, the world is stared down. Nikolaus Geyrhalter, forever working in wide-shot, frames up and presents his true-life landscapes with the eye of a high-end still photography artist. Then, he holds and holds his shots, just long enough to digest, but then cutting away before whatever question the shot is asking could be resolved. If anything, the viewer has accumulated more unresolved questions than before. And when it comes to how we as people reconcile our ever-changing, diverse yet universally relatable world, questions are what fuel our empathy, our attempts at understanding. It is precisely those qualities that documentarian Nikolaus Geyrhalter is interested in mining.

Though still relatively young, the Austrian documentarian boasts an expansive filmography, both in terms of decades worked and miles traveled. He’s not here to be an activist with a camera, nor is he a Wiseman-esque fly on the wall. Geyrhalter is fixed upon raw, basic truths, sometimes via conversation; always via observation. People and places are they are, perhaps as they were, and even, on the occasion of his newest film included here, what they will become.

With this fantastic new set, Icarus Films showcases six of Geyrhalter’s most essential films. Boasting excellent transfers and audio, not to mention an expert array of subtitling of languages from all over the globe, the primary lament of this collection is that only one of the six films (2005’s Our Daily Bread) is a high definition Blu-ray. Everything else is available on standard definition DVDs. All of it, though, is handled with utmost care, regardless of the disc format.

HOMO SAPIENS (2016)

Where are we? What are we doing? What have we done?

A deeply melancholy dwelling on a screwed-up death of everything. Despite the title, we see no Homo sapiens; merely their fading fingerprints on what they’ve erected- and now, for whatever reason, abandoned. Destruction, overgrowth and the occasional animal. Nature is silently yet aggressively reclaiming what we’ve built.

Offices, shopping plazas, historic structures, all of it pillaged, ransacked, and forgotten. With no choice but to surrender to the uneasy stillness of the images, we become absorbed in this haunting meditation. Geyrhalter’s symmetrical framing make it eerily easy to fall into his reflective trance. Look at it all. Just... Look at it. Only the wind bothers to come through anymore. It’s all so quiet that the sound of the flapping wings of a small bird can dominate the inside of an empty cathedral. Allen Davieu-esque beams of light pour through rotted openings in roofs and ceilings, as though the Lord is assuring His presence to the camera. Or maybe it’s just that the sun is out and there’s far too much airborne dust and debris to conceal it.

The director’s penchant for centric exactitude is reinforced with every shot, conventional order be damned. Though often enough, Geyrhalter nails that, too; presenting a yin and yang of light, darkness, lines, shapes, focus and depth. Each shot is breathtaking. This is a film so remarkably still and contemplative, the peak of the action is when a bird happens to fly towards the camera, nearly one hour into to ninety-four minute running time.

From the signage, the architecture new and old, we can deduce that it’s a far eastern country. That much is clear. According to the booklet included in this set, Geyrhalter actually shot portions of this film on different parts of the globe. The abandonment and desolation of it all? Much of it orchestrated, even dressed for the camera. So claims Geyrhalter in his included printed interview. Yet, to these western eyes, it is a landscape twice removed- first by foreign culture that established it, then by the unseen forces that are now ravaging it. And the truth of that is not so different from truth of the images.

Contemporary, human notions of beauty have lost all value in this place; yet thisisbeautiful. It is a resonant, horrific beauty, one assuring us that we are indeed fleeting, and that this planet, indeed all of creation, will outlive all of us.

Where do go? Whom do we look to? What do we change? What do we surrender?

OVER THE YEARS (2015)

The day they closed the factory down they had nothing,

Nothing left to say"

"So they're talkin' of the changes the closing brings about.

Talkin' of the hard times and the young folks moving out.

Yes, they're talking as if talking can make everything all right.

But all the talking ever done won't bring him back tonight.

Ah, tonight.

That’s part of the song “The Day They Closed The Factory Down”, by the incomparable Harry Chapin. In Geyrhalter’s three-plus-hour documentary Over the Years (Über die Jahre), the last handful of loyal employees of the longstanding local, oversized textile manufacturing factory finally lose their jobs. To hear them tell it, their region of Waldviertel, Austria has never been the easiest place to get by. So desolate has the employment climate been, that the citizenry has long looked at the factory as an inevitably finite institution, a place with its own built-in doomsday clock. When it strikes, it’s the worst kind of strike any factory could experience. Worse than any picket; worse than any match fire. And strike it does. Off frame, between the scenes.

That is within the first thirty minutes of this three-plus hour-long film, an ambitious commitment wrought, no doubt, between the cracks of other projects and life itself for Geyrhalter. Each year, give or take, he would revisit the half-dozen or so denizens of the factory, checking in with them long-term in regard to how things are going professionally, personally, and the like. It’s fair to say, one supposes, that, this being Austria, the emotional remoteness displayed throughout is somehow ingrained, generationally passed down, et cetra. (To that line of thinking, perhaps the same logic could be applied to Geyrhalter’s wholly unique filmmaking craft). Yet, the chronic uncertainty, the sometimes-hopelessness, the lingering years-running desperation, is felt. Geyrhalter’s unflinching long takes filter nothing.

Still a young man when venturing into this project, its tremendously interesting to track his pool of characters over the years. Alternating from person to person to person, as their family situations, their job situations, their home situations change and morph and stagnate and rarely flourish, Geyrhalter needs no title cards or on-screen identifiers to communicate passage of time nor to remind us who is who. It’s clear, and we know. One thinks of Richard Linklater’s jewel of a film, Boyhood, what with its sublime depiction of real time playing out in a mere three hour film. Linklater may’ve arrived at the finish line first with 2014 Oscar contender, it’s true.

But beyond the shared usage of return filming over the course of a decade, Boyhood and Over the Years are different animals. There’s the difference between narrative and documentary, the entire growing-up conceit of Linklater’s project versus a more Michael Apted/“UP-series approach”, in which real people are revisiting across stretches of time, simply to see how they’re doing. The primary “family” in play is that of the former textile workers- a unit that doesn’t seem to miss one another all that much once their time there ends. There is a single reunion gathering at the old place of employment, but aside from that nudge down memory lane, these people seem to be doing what most anyone would do- moving forward, with no need of looking back. They already understand that talking about the changes in their lives won’t make everything all right, particularly talking on camera. But begrudgingly, they do anyway, throughout an entire decade. And from their quiet forthrightness, and the complete lack of condemnation from the filmmaker, we are let into their minds, their plights, their worlds.

ABENDLAND (2011)

In ninety minutes, Abendland displays humanity in most all its forms, all its modern permutations. Boiled down, the film could conceivably be dismissed as an arbitrary assemblage of still observations, lingering and long tracking shots that painstakingly follow a rolling gurney, a tray of chicken dinners, or just the sound of a thumping house beat through dense congregations of people. Never do we know just what everyone featured is up to, nor who they are, nor where we are. ButAbendland, nonetheless, runs the gamut, and quite effectively. It cannot and should not be dismissed.

Translated from German to English, Abendland is “West” or “Western World”. Shot entirely at night in Germany, Geyrhalter simply casts his camera into whatever environment he’s monitoring in that moment. There is never any explanation, not even for the conceit of the entire film itself. In so, one would not be blamed for wondering just what the security officer driving around in his high-tech truck has to do with the dull folks working late in offices. Or, what hurried caterers have to with online pornographers (warning: there is a scene of explicit, coldly observed sex). It’s what people are doing at night. No apparent order or logic to the sequences, as jarringly different as they can be. No interviews, simply observation in long takes and wide shots.

Abendland doesn’tsit apart from the other films in this set as one may suspect. It might just be the director’s most direct statement on the fractured priorities of people, in relation to each other. Everyone here has let their guard down to some extent- including us.

OUR DAILY BREAD (2005)

Where does our food come from? And do we really want to know?

In 2005’s Our Daily Bread, Geyrhalter grants access to some absolutely massive “food factories”; huge, well-staffed cavernous complexes housing pigs, chickens, cows, and even fish. Yes, the animals are all there to be worked-through and slaughtered for food-making purposes, and yes, those processes are depicted in the same wide angled, unmoving manner that every moment of this film is crafted.

We follow the progress of mass-scale pig slaughter from sudden death through to processing. The pigs, freshly cut and strung up by their hind legs, look oddly fake; like a gory maquette found in a haunted attraction. Here hangs our future bacon, our future pulled pork. And down the line it goes...

The workers are so locked-in, so on-task, that they seem every bit as mechanical as the steel machines around them. Garbed in lab coats and safety classes, clinging to clipboards, pens, and/or hand-tools intended for unpleasantness, there is an eerie quality in not just what they do, but how they are. Perhaps when knowledge of the toxic becomes toxic, all one can do is to keep on keepin’ on. Punch in, punch out. It is assumed that the filmmakers briefed the workers not to speak; the verbal silence causing sharper focus on whatever they’re doing- but also upping the weirdness ante. The weird vibe does a lot to inform the overall tone of Our Daily Bread, even when Geyrhalter leaves the animal processing plants to spend time in cavernous underground salt mines (amazing!) or a vast outdoor field; just as a crop duster zips symmetrical overhead, doing its prescribed task.

Off-putting vibe aside, there is an indisputable central importance to what Our Daily Bread is doing. The modern processes of keeping the developed world fed should not remain shrouded. These, and places not unlike these the world over, are the behind-the-scenes reality of our breakfast, lunch and dinner. And just when one may assume that Geyrhalter’s underlying goal is to flag up the inhumanity of the processes on display, he makes a strict point of showing the food workers eating lunch. These people too, must eat. The reminder is repeated throughout, no matter where the camera goes.

It is sobering, though, to realize that of all the dangerous and potentially toxic environments that are represented across the course of this entire DVD set, the booklet’s cover photo of a cameraman (presumably Geyrhalter) decked out head to toe in a protective disposable white jumpsuit and gas mask was taken in a food processing facility. Not a nuclear power plant that’s melted down in the past. Not any of the highly sanitized tech environments of Abendland. A food processing facility. Dare we chew on that?

For whatever reason, Our Daily Bread is the only film of this set that is served up on high definition Blu-ray, as opposed to regular DVD. Though the visual magnificence of the other films comes through, the HD bump given to this one does show. It’s something to be thankful for, with Our Daily Bread.

ELSEWHERE (2001)

Geyrhalter’s four-hour endeavor Elsewhere is a grand achievement that’s truly global in scope. In twelve separate segments, he takes us to the farthest reaches of the globe, and, while unseen and unheard in the film, he gets to know people there.

Shot throughout the entire year 2000, Geyrhalter chucks aside any forward-facing Western futurism that the turn of the millennium generated; instead visiting cultures rooted in ages-old tradition and simple survival.

Each of the twelve segments is devoted to a separate locale, shot one per month. Extremely remote regions of Siberia, Italy, India, British Columbia, Indonesia, even the island of Micronesia, are featured. In each place, Geyrhalter finds and sticks with two or maybe three connected individuals, cultivating serviceable demonstrative narratives. Whether a well-bundled lone reindeer herder transversing the white slopes of Finland or the Namibian sister wives of a goat herder named Kapyarukoro trying to figure out their relationship to him and one another in their arid clothing-minimal desert community, Geyrhalter comes alongside of all of them.

The glossy booklet that comes with the set breaks down each location, as well as the ridiculously extreme processes to reach them: “12 remote places on five continents, 350 kg of filming gear, generators, tents and catering, which were transported by planes, helicopters, bushcampers, boats, dugouts, dogsledges, camels, mules, snowmobiles and porters, 70 take-offs and landings, more than 240,000 flight kilometers (that is about six times the circumference of the earth) and some thousands on land, too.” Even without all that amazing effort as part of the story (and it’s not), Elsewhere shines bright as the rare global travelogue that completely spotlights the residents, the natives, the denizens, the people. It is in no way made to be about what an undertaking of travel and/or production it is, leaving those quick details to the DVD booklet. Elsewhere simply lives up to its names in the filmmaker’s starkly minimalist approach. And just when you begin to settle in, it’s off to the next place...

PRIPYAT (1999)

You can’t see it and you can’t smell it, but it’s there. It’s lingering radiation from the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown, and not going anywhere. The people of Pripyat know this all too well, as they’ve nonetheless opted, for whatever reasons, to remain in residence inside of the thirty kilometer contaminant zone.

Pripyat is the village that housed the employees at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, a thriving area prior to the disaster in late April of 1986. Most of the 100,000 former residents have relocated. Four of the remaining few are the reoccurring subjects of this earliest of entries in this Geyrhalter DVD collection. Made for television, and rendered in an oppressively muted greyscale, Pripyat is a talkier affair than the other works of the filmmaker represented here. By comparison to something like Homo Sapiens or even Abendland, it’s pretty clear that this is an early work. Though, it is also recognizable as the early work of an emerging artist to be reckoned with.

Amid the abandoned homesteads and derelict businesses of the zone, there remains several large Soviet propaganda style signs, encouraging responsible energy usage, And bolstering the residents scientists for the greater good. But the reality of Pripyat is merely one hard cutaway: (more) overgrown fields of abandoned vehicles, some of which would qualify as major Cold War era military machines, sitting alone to forever soak in their own radiation. The camera follows handful of workers through these fields, they themselves long ago resigned to an unspoken fatalism regarding their own continued exposure. {Shrug} “The radiation is invisible. They say I must be used to it by now.” Then awkward silence. This is a uniformed guard whose need to feed his family has led him to a state-issued likely early doom, all in the name of keeping nearby pheasant farmers from pick-and-pulling replacement parts for their own dilapidated equipment.

It’s simply a ghost town, void of even mice and birds at this point. As one of Geyrhalter’s four key subjects lead us on a long unbroken foot tour of once lively school property, openly lamenting has such a disaster could’ve happened, her attire of a camouflage jacket over a flowery dress perfectly encapsulates her existence of forced survival amid mundane and office work. Her eventual arrival at her family’s former Apartment is a heartbreaker. The place of her former happy life is now a vandalized shell of peeling paint and faded wallpaper. The windows are broken, everything is contaminated. She can barely even speak about it. And who could blame her?

Regarding the DVD set itself, the raw and real Pripyat is an ideal full-circle from the much newer acknowledged artifice of Homo Sapiens. Both wield the ability to deeply move via Geyrhalter’s ability to unflinchingly evoke the lost human spirit in abandoned places. It’s tragedy; past, present and no doubt future. For us, we have this document; one that no viewer would soon forget.

*****

Simply being within the frame of a Geyrhalter film doesn’t so much grant one absolution as it does a certain humanizing. Native peoples aren’t touted for their exoticism; food factories aren’t verbally called out for inhumane treatment. In his trademark exclusiveness of long takes, wide shots, and twenty-second long static shots, Geyrhalter takes us on a beautifully lulling yet appropriately uneasy tour of our planet. If you have to have it all explained, you will have to look elsewhere.

This an filmmaker every bit the artist as he is an explorer. There’s a rigid defiance in that, something that only enriches these six particular films. There are more films that Geyrhalter has made, but for now, this fine set will do. They leave us with no question that the lessons of the films of Nikolaus Geyrhalter are nakedly before us.

Elsewhere

Director(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

Writer(s)

- Silvia Burner

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

- Michael Kitzberger

- Wolfgang Widerhofer

Pripyat

Director(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

Writer(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

- Wolfgang Widerhofer

Our Daily Bread

Director(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

Writer(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter (screenplay)

- Wolfgang Widerhofer (screenplay)

Cast

- Claus Hansen Petz

- Arkadiusz Rydellek

- Barbara Hinz

- Renata Wypchlo

Homo Sapiens

Director(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

Writer(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter (concept)

Over the Years

Director(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

Writer(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

- Wolfgang Widerhofer

Abendland

Director(s)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter

Writer(s)

- Wolfgang Widerhofer (script)

- Nikolaus Geyrhalter (script)

- Maria W. Arlamovsky (script)