Sound And Vision: Jérôme Vandewattyne

In this Sound and Vision, an exclusive interview with film and music video director Jérôme Vandewattyne.

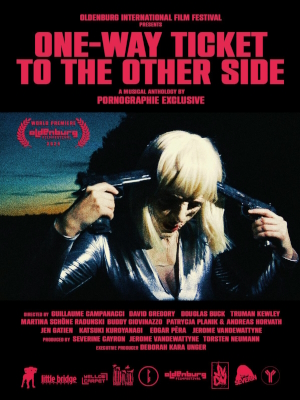

Jérôme Vandewattyne and Severine Cayron are two members of the band Pornographie Exclusive, and co-directors, co-producers, writers of the album film One-way Ticket to the Other Side, which also has segments by the likes of David Gregory, Douglas Buck and Buddy Giovinazzo. Jéròme is also the director of cult films Spit'n'Split and The Belgian Wave, and directed dozens of music videos (some of which are sampled below this interview). We spoke to Jérôme via e-mail.

How did One-way Ticket to the Other Side come about?

It's very complicated to know exactly where the first idea comes from. With Severine Cayron, my partner and the other brain of Pornographie Exclusive, our cold-wave/electro-rock band, we don't compartmentalize art. One thing inspires another, and that makes our artistic life fluid and constant. I think it all stemmed from a dream Severine and I had when we first created our songs. We wanted to turn it into a kind of anthology film, bringing together a series of international independent and genre filmmakers. We wanted to pay tribute to the cinema that made us tick.

Little did we know that this dream would come true as quickly as we'd imagined. Our first desired collaborator was Douglas Buck, whom we'd met at the Oldenburg Independent Film Festival in Germany. We'd seen his film Family Portraits and started exchanging e-mails. Then video calls became more frequent. Douglas started writing a short film based on our track Icon, which I was supposed to direct, and then wanted to write and direct a second act of the story, more intimate and closer to his artistic sensibility, on the track Electric Blue, which follows Icon on the album.

Unfortunately, the first versions we put on paper were too expensive for our type of economy and we had to rethink the production. Meanwhile, Douglas had a new idea for the track that followed his segment. The ball was rolling. That's when we said to ourselves that we could make our dream come true and call directors for every track on our album. We then thought it would be interesting to do the opposite of the classic film process, which consists of creating the images and then the music. Here, the basis would be the music, which would inspire the image.

How did you get the roster of people (including luminaries like Douglas Buck and Buddy Giovinazzo) to be involved?

Since Douglas Buck and us met at the Oldenburg Film Festival, it seemed natural to propose this project to Torsten Neumann and Deborah Kara Unger, who organize the festival and have supported me since my first feature Spit'n'Split. It was clear to Severine and me that they were the only ones who could understand this wild and free project, in the image of their festival.

Since Douglas Buck and us met at the Oldenburg Film Festival, it seemed natural to propose this project to Torsten Neumann and Deborah Kara Unger, who organize the festival and have supported me since my first feature Spit'n'Split. It was clear to Severine and me that they were the only ones who could understand this wild and free project, in the image of their festival.

They embraced the idea with great enthusiasm, and suggested that we surround ourselves with filmmakers who had ties to the festival, to create a family - the Oldenburg alumnis. My first encounter with Buddy Giovinazzo was also at this festival. So we contacted Buddy for the anthology, who during post-production kindly allowed us to use two tracks from his films Combat Shock and Mr. Robbie, composed by his brother Rick Giovinazzo, for our interludes. Buddy is very close to the festival and Douglas Buck, as well as David Gregory from Severin Films. It was a snowball effect. Then we asked Edgar Pêra, whose work we loved, Truman Kewley, whose first feature Beautiful Friend had stunned us. We were also put in touch with producer and director Jen Gatien from New York (Men of War), Martina Shoëne Radunski from Berlin (Flieg Steil, co-directed with Lana Cooper), Guillaume Campanacci from Cannes (Whenever I'm Alone With You, co-directed with Vesper Egon), Patrycja Planik from Warsaw (Faggots), Andreas Horvath from Vienna (Lillian), and finally Katsuki Kuroyanagi from Japan (The City) who impressed us with his quality and speed. His segment was shot and edited in less than 24 hours.

Despite the short time we had to put the film-show together, Torsten Neumann and Deborah Kara Unger never doubted or restricted the artistic process. On the contrary, they always pushed us further to come up with a project we'd be really proud of. They really are our cinema godfather and godmother, they've been really stunning.

How do you go about wearing several 'hats' in the making of this 'album film', being part of the rock-group Pornographie Exclusive, being a producer, being a writer, being a director?

By sharing these hats with my partner in crime, Severine. We are two brains in this business, very complementary. We followed up each film with each director, and handled production remotely with Torsten and Deborah. All this while preparing the live music and directing and starring in our twelve segments, which we edited and sound designed. We worked together with a lot of close collaborators. There's no secret about it, we put a lot of time into it. Severine and I spent our whole summer working very hard on this project, without seeing anyone except our co-producers Torsten and Deborah and all the directors by video call. But when we see the feedback we've already had from our shows in Germany and Canada, we'd happily do it all over again.

Do you approach a long-form album-film like this differently than your music videos?

Yes, it's quite a different process. First of all, there's the collaboration with the other directors, which requires a certain letting go, but which is very exhilarating for creativity. With Severine, we readapted certain situations or dialogues from our interludes, which serve as the film's common thread, according to the films we received. It was an extremely enriching experience. Although there was a lot of freedom, the process was very well thought out. It's still a film that demands a certain consistency, even in its surrealism.

How do you make an album-film on what I suppose is a fairly small budget? Are there any good stories from the set?

How do you make an album-film on what I suppose is a fairly small budget? Are there any good stories from the set?

The budget was very tight indeed. We had a symbolic sum of $99 per film. It was really the desire to make a band film that drove the project. The aim was to talk directly from creator to creator without middle-men. Each director sent us good vibes, which we shared with them in return. And then, the ultimate reward was to be able to share the project at the Oldenburg Film Festival, with a big real audience, where we were received like rock stars by the organizers and their fire team.

A rather juicy anecdote is the creation of our From A Bridge View segment. We had planned to introduce Icon with a strange catwalk, lit only by the characters' van. However, a sudden change of location caused by the arrival of destructive gangs prompted us to rethink the mood, transforming what was intended as a simple interlude into a full segment. We shot and composed From A Bridge View in 48 hours, a true creative trance. We were caught up in our own game, and it was a real pleasure.

One of the segments uses generative A.I. There is a lot of discourse about the use of AI in low budget filmmaking. How do you personally feel about it, and is AI a blessing, a curse or both?

The segment you're talking about is Slander and was directed by Edgar Pêra. Edgar has made a feature film entirely in AI called Telepathic Letters, which was shown at Locarno Film Festival this year. The film imagines a fictional correspondence between Fernando Pessoa and H.P. Lovecraft. Some people call it genius, others think it's not real cinema. Severine and I were very impressed by the film, and by Edgar Pêra's work in general. In fact, we wanted to work with him because of his off-system approach. He is known as an image researcher in the same way as Jean-Luc Godard was (they actually collaborated together with Peter Greenaway in a film called 3x3D). His work on AI, completely changed my point of view or rather brought nuances.

First of all, Edgar Pêra explains that this technology should not be called "artificial intelligence" but rather "artificial stupidity". There is no intelligence in this technology, there are only humans behind it. It's not so much the fear of what this technology could become that's scary, but what humanity can do with it that's terrifying. Once again, in this whole AI debate, as with other subjects, human beings need a scapegoat to avoid really questioning what is at the root of the problem. We're afraid of ourselves, and AI is just the consequence.

Edgar Pêra takes the problem in the other direction. Why not create a movement to make this technology positive? Take advantage of the opportunity presented by this tool, which can turn out to be a wonderful assistant if you take it as it is, to build rather than destroy. I really like his approach. Some pessimists, who might call themselves realists, would say that the battle is lost in advance. Edgar Pêra defends the idea that we must resist, and steer the algorithm towards greater subtlety. Just as when we look at the videos on social networks, the choice is ours. If all you come across are stupid videos, ask yourself the right questions.

As far as I'm concerned, the use of AI for low-budget films is not a bad thing, contrary to what I've read in some of the statements made by more established filmmakers. There's already an "economic antinomy" here, if I can put it that way. A Hollywood filmmaker can't speak for today's starving filmmaker. But what's the real problem? That the film isn't really filmed? What can we say about these films that are 90% special effects spend and gather indecent sums of money? I find this attitude condescending and very bourgeois. Some real questions could be: what's wrong with the spectacular being accessible to all? Do some people feel their wallets are under threat?

Of course, there's the argument that the danger is for graphic designers who earn their living and whose jobs may be threatened. But that would be a distraction from the real problem. It's not AI that's threatening employees, it's the bosses who are looking for profit at the lowest possible cost, and who have no regard for their staff, whom they see only as pawns. The problem isn't the filmmaker who's going to use AI for his micro-production and try to make a splash.

The problem is the big studios who are planning to lay people off. What's important to defend is craftsmanship. A director like Edgar Pêra, who works with his very small team on a film in AI every day for 2 years, is a craftsman. And Edgar will agree with me that, in any case, it's not the spectacular that makes the body of a film. It's not its grain or whatever. The most important thing is what's inside it. Its story or deeper meaning, it's not just its packaging. Once again, I think it's the way we use the tools at our disposal that determine whether the process is acceptable, by placing it in an economic and social model.

One thing I noticed in your music videos, The Belgian Wave, Spit'n'Split and One-Way Ticket to the Other Side, is your use of typography, that is very distinct. How do you approach this aspect of your movies and music videos?

I'm glad you pointed this out, because not many people pay attention to it, and it's very important to me indeed. The credits, the typography used, are just as much a continuity of the work as the theme of the film, the music, the color grading or an editing effect. Typography tells as much as the screenplay and directs the viewer's experience. Typography sets a mood, can bring nostalgia, sets the tone of a film. I love the impact that typography can have on me as a viewer - love or rejection. I don't believe in the seriousness of a film that takes the first typography its graphics- or editing-program suggests. And it's often the most serious ones that use the default setting. I tend to believe that a film's DNA can be felt in its typography alone. Even if it's in bad taste, at least it's got personality.

Music has been a big part of all of your films to date, so hard question: if you had to choose. Music or film?

Music and cinema are part of my DNA, one wouldn't exist without the other. They've always been intertwined, like a battery that couldn't function without its positive and negative sides. If I lost one or the other, I wouldn't exist; there wouldn't be any life impulse.