Blu-ray Review: EL SUR, Time, Memory, and Parents Confound in Victor Erice's Film

An outstanding sophomore feature from the Spanish director continues to grapple with emotional life under fascism.

I last saw Spanish director Victor Erice's debut feature, The Spirit of the Beehive, about ten years ago, around the release of Pan's Labyrinth, of which it is a clear influence. I took another look at the film -- the director's most notable on the worldwide stage -- this weekend before diving into Criterion's delicious new Blu-ray of Erice's second feature, the 1983 period drama El Sur.

The detour was largely unnecessary (Spirit of the Beehive was right where I left it, a dreamy quasi-horror movie of the way a child's mind makes meaning) but it's difficult to ignore the direct parallels between Erice's first and second films. Both revolve around wide-eyed children, both girls, both young actresses (I learn from El Sur's special features) pulled from the same school in Spain by the director and his team. Both films reflect back on the early years of Franco's fascist rule of Spain. Beehive was made shortly before that rule's end, and El Sur immediately after.

Both films contemplate the breaking of a nation's heart in deeply-felt, allegorical character dramas. Of the two, El Sur is the easier watch -- more straightforward in narrative, and direct in meaning. It centres around Estrella (8 years old for most of the film, played by Sonsoles Aranguen; later a teenager, played by Iciar Bollain), who is reflecting back on her life as a child, during a period in which she slowly became aware that her father was in love with another woman, not her mother.

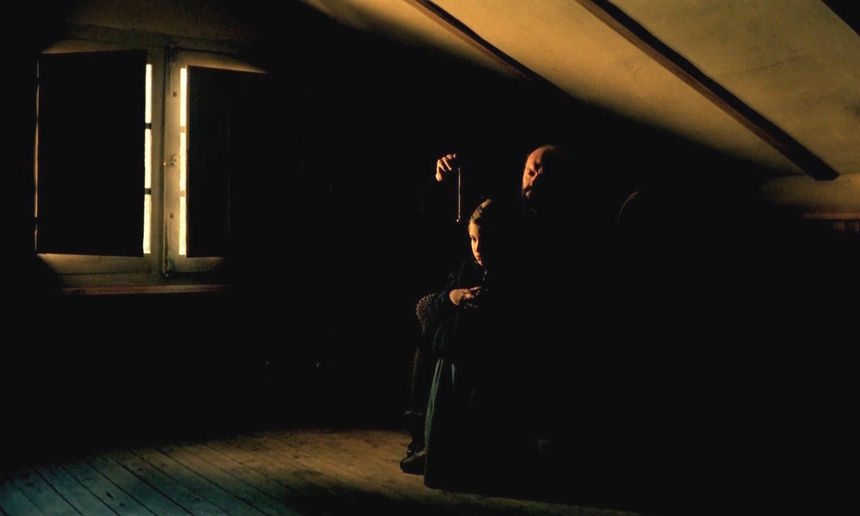

Voiceover narration from Estrella as an adult -- a woman piecing together things she half-understood as a child -- gives the film the aura of a Michael Ondaatje novel. Estrella's father Agustin, played with careworn rebelliousness by Italian actor Omero Antonutti, is almost a wizard character, all dowsing rods and divining pendulums. His behaviour, even at home, is perpetually cloaked in arcane symbol and portent that the child Estrella cannot reason out, nor particularly cares to.

She is in the process of working out her own understanding of how the universe operates and, then, how she operates within it. "The South" -- El Sur of the title -- is a liminal space on the edge of her knowledge of the world, from which her father emerged; it occasionally sends envoys (her grandmother and a delightful old nanny visit for Estrella's first communion) and beckons from beyond the frame with cheery postcards and the possibility of working out some aspect of why Agustin is slowly, painfully withdrawing from the family.

The introduction of teen Estrella at the beginning of the third act allows for the intersection of three or four lenses on the memories of the character's childhood: her childlike one; her adult musings; her teen perceptions of the behaviours of her father. All of this is layered over what her father recalls, and doesn't recall, about the same incidents in the story; if Agustin could ever have dreamed that something like writing an actress' name on an envelope over and over would have such a lasting effect on his daughter, he might have inquired more deeply into how to discuss it with her one day. Instead, and especially in light of the film's abrupt and disturbing ending, moments like that remain a keyhole only, though which Estrella might peer, seeing only a portion of the picture.

I found the film utterly absorbing, and found -- if anything -- the rubric of its plot less beguiling than the way it analyzes Estrella's memories, in parallel with her nascent maturation into a young woman. A quiet confrontation between father and daughter in a restaurant, where they talk of boyfriends and old loves, is brutal, both for Estrella's carelessness and Agustin's hopelessness.

Photographed by José Luis Alcaine and transferred at 2K for the Blu-ray release, El Sur is neither as visually over-the-top as its predecessor (no honey-coloured window panes in this household) nor as abstract; it's a pleasure to watch throughout, and Alcaine's cunning use of interpolated light and shadow -- particularly in the long, slow reveal of the opening shot -- are delightful.

Extras on the disc are unusually robust. There is a one-hour televised panel between four critics discussing the film, and a "new" making-of documentary, edited from interviews with the principal cast recorded in 2012.

More intriguing, however, is the material regarding the intended ending of El Sur. It was meant to have been a much longer film, and was to include a full additional hour in which Estrella does, indeed, journey to the South to conclude her own story and solve the puzzles of her father's life. A 21-minute interview with Victor Erice, recorded in 2003, serves as something halfway between a monologue and a deleted scene, as he describes what the second half of the film would have (in his mind) accomplished. Erice holds that removing the Andalusia sequences "shattered the moral dimension of the story" by curtailing the theme of initiation and understanding that runs through the movie.

This may well be, though I find it interesting that in the film as it exists, the strong suggestion of Agustin's gift of the pendulum to Estrella in the opening sequence is that the future -- and his "power" over it, whatever that may be -- is hers now; in the extended version of the film that Erice describes, the pendulum instead symbolizes Estrella's obligation to her father's story, rather than the potential of her own.

To allow for better comparison, the Criterion disc includes Adelaida Garcia Morales' novella as well, along with a discursive essay by novelist Elvira Lindo in which she addresses both the extant film, and the film-beyond-the-film that continues to haunt the director.