70s Rewind: FAT CITY, Broads, Booze and Boxing, Bleakly

To be honest, I didn't feel that good before I finally started watching John Huston's adaptation of Leonard Gardner's novel the other night, but afterward, it was only the sheer exhaustion of a long day's work that allowed me to close my eyes and fall asleep.

It is a downer, man.

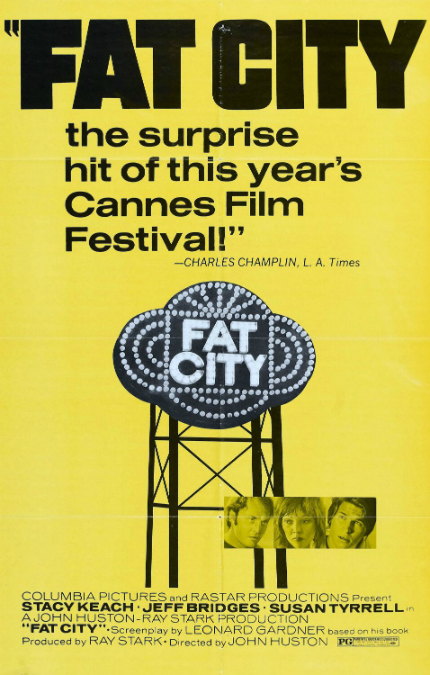

Gardner's novel, which was originally published in 1969, caught the eye of producer Ray Stark, who passed it along to director John Huston. The two had worked together on The Night of the Iguana (1964) and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1969), the latter starring Marlon Brando. Reportedly, Huston wanted Brando to star in Fat City, but when that didn't work out, Stacy Keach got the nod.

Some three decades into his directing career, Huston was, let us say, not on a roll. A Walk with Love and Death (1969), starring his young daughter Anjelica Huston in one of her first screen roles, was a flop in the U.S., which was perhaps typical of a period for the director that also included box office disappointments Sinful Davey and The Kremlin Letter.

One can easily imagine that Fat City resonated strongly with Huston, who had himself boxed in his younger years. Keach plays Tully, a former boxer now about to turn 30 with no firm prospects ahead. What will he do with his life? He feels that his career was taken away from him through the evil machinations of his manager, but there is little hint that he ever would have achieved big success in the ring.

As we meet him, Tully is single and living on Skid Row in Stockton, California. He decides to head to a gym and get in some work, where he spies a more youthful aspirant, Ernie (Jeff Bridges), and invites him to spar. It doesn't take long for Tully to realize he is overmatched; at the age of 18, Ernie may not have any boxing expertise, but he is fit and healthy and has a ton of potential.

The film then follows Ernie and his travails as a beginning boxer under the tutelage of eternally optimistic manager Ruben (Nicholas Colasanto) and assistant trainer Babe (Art Aragon), who is always in full agreement with Ruben. We also meet Faye (Candy Clark in her film debut), a beguiling young woman who quickly attaches herself to Ernie.

Like all his fellow young boxers, Ernie believes the sky's the limit, but he soon falls back to earth after his first amateur bout. He must answer the question for himself: where do I go from here?

Returning to Tully's story, Fat City finds him in a bar where he strikes up a relationship with Oma (Susan Tyrell, just 26, in an Academy Award-nominated performance). It's a scene that flirts with hope before descending into overwhelming sadness. Tully and Oma are both alcoholics; the difference is that he is still fooling himself that he can have a better future, and she has already given up all such hope.

Returning to Tully's story, Fat City finds him in a bar where he strikes up a relationship with Oma (Susan Tyrell, just 26, in an Academy Award-nominated performance). It's a scene that flirts with hope before descending into overwhelming sadness. Tully and Oma are both alcoholics; the difference is that he is still fooling himself that he can have a better future, and she has already given up all such hope.

Beautifully photographed by Conrad L. Hall (Harper, In Cold Blood), the gloomy atmosphere reigns even when the California sun is shining brightly. The productive fields of the northern San Joaquin Valley, where Tully must find work, are made to look uninviting and oppressive, which must reflect his state of mind.

Keach and Tyrell have the more showy roles, such as they are, yet it's Bridges who really shines, edging Ernie's vulnerability forward and then backward, a boxer who shies away from emotional conflict. Colasanto, who left an indelible impression on me because of his performance as Coach in TV's Cheers, is simply marvelous here, teaming with Aragon to present a united, if dim, front; they want to help their boxers, but they don't really know how.

All the characters could easily be considered "losers," I suppose, especially in contrast with the heroic, ripped athletes who would burst forth a few years later in Rocky, where the good and true and humble would always win by wearing their hearts on their sleeves. The women in Fat City are not given any true depth: they are whiners and clingers, not deserving of further attention, really, according to the filmmakers.

But it's hard to argue much in favor of the men, either. They decline to face reality, instead talking about something better, without taking decisive action to improve their lives. They can't even dream right.

The film is available in limited-edition Blu-ray from Twilight Time. The picture looks quite good; colors, bleak as they are, look accurate and the blacks are sufficiently inky to convey the lives that emerge from the shadows.

Special features include an isolated score track, featuring original music by Marvin Hamlisch, and the original theatrical trailer, which is in very good condition.

After I wrote the above, I listened to the marvelous audio commentary by film writer Lem Dobbs and music expert Nick Redman. They present their thoughts in a convivial fashion, offering up their informed insights and disagreeing occasionally in an agreeable manner. They have much to say about the actors, the location, and especially about Huston and Leonard Gardner; Dobbs points out all the differences from the novel.

Toward the end of the commentary, Dobbs mentions other directors who had reportedly been approached by producer Stark before Huston came on board. Mention is also made of Keach's surprise and dismay that 15 - 20 minutes of footage near the end of the film had been cut.

This was also mentioned in a review by John Simon, published at the time of the film's release in September 1972 as reprinted in his book Reverse Angle: "I hear that Columbia Pictures considered Gardner's screenplay and Huston's film too downbeat, and cut a lot of it out." (Simon, by the way, thought far less of the film than the commentators.)

Simon thought the film, as released, was too "disjointed," and I can't argue with that. Fat City is far more interested in offering up gobs of boozy atmosphere filled with broads and boxing through a bleak lens. Yet is also feels very sympathetic; there are no villains, except viewers who look down their noses at people who may be having trouble connecting the dots.

One may find it hard to sleep after watching Fat City, not because it haunts nightmares, but because it feels too real -- and relevant -- to ignore.

70s Rewind is a column in which the writer ruminates on his favorite film decade.