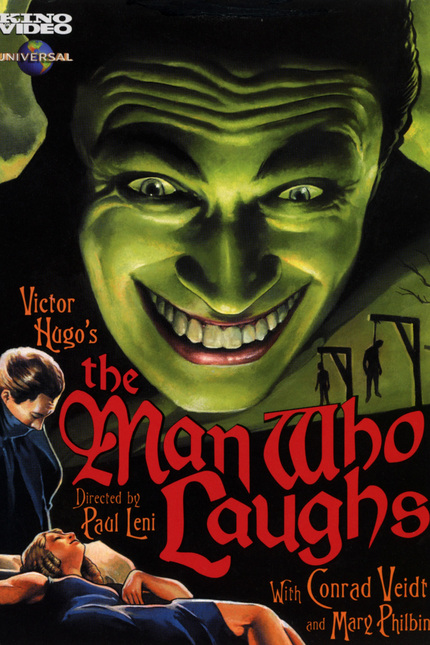

Psycho Pompous: Expressionist Horror, Part II: The Man Who Laughs, An Expansion

The Man Who Laughs is, for the most part, not a horror film. It is a melodrama and a tragic love story in which many of the melancholy elements are twisted into a haunting gothic representation of the emotional states of the main characters. Now... Why are we spending yet another installment of this column talking about this film? Besides finally getting to the movie itself, it’s because The Man Who Laughs injected the right elements into the horror scene at precisely the right time. This is when (in American horror filmmaking) the priority would shift from light to shadow, from daydreams to nightmares. German expressionism had arrived to upset the storytelling pastimes and ideals of American romanticism, from which horror films would never be the same.

Without this movie, the Universal Age of Monsters would not become as popular as it did, catapulting the horror genre into the hearts and minds of the mainstream audience by directly influencing movies such as James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) and Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932). This was not due to an overwhelming audience popularity, but of a significant impact the work had on then-contemporary filmmakers in terms of using malformations and body horror as a means to explore dejected and victimized characters. This broke down the consistent trope of the time in Hollywood that evil and good exist as categorically different kinds of people instead of existing on two sides of the same coin in every person. The only major films that had approached this dichotomy in this way as of this point in the United States was John Robertson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920) and Wallace Worsley's The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923).

The first shot of the film is that of 17th Century England where King James II (Sam De Grasse) sleeps in his bed chambers whilst being observed by decrepit religious statues. The intercutting of religious icons and the crumbled faces of the statues craning down on the king act as silent judges of all that has and will take place. Though this can be taken to mean that King James will face the wrath of Heaven, it ultimately means nothing; such saintly righteousness is no longer alive in the film’s world, and its memory is crumbling to dirt. This attitude is only made stronger by way of the king’s jester Barkilphedro (Brandon Hurst) entering from a secret passage from behind one of the statues to wake the king, insinuating a pious facade masking a darkly cynical truth. This stellar art direction was accomplished by the ungodly talented Charles D. Hall, who would craft Universal’s designs for iconic horror and thrillers such as Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932), Frankenstein, The Invisible Man (1933) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Browning’s Dracula (1931), and had previously teamed up with Paul Leni on The Cat and the Canary (1927).

Barkilphedro informs the king his that elusive enemy Lord Clancharlie (Conrad Veidt) has been captured, and leads James like Mephistopheles through a hidden snaking passageway reminiscent of Joh Fredersen being led by Rotwang through the bowels of Metropolis (1927). James confronts Clancharlie as a rebel who refused to bow before the rightful king, though the real reason is because James has kidnapped his son Gwynplaine (Julius Molnar Jr.). James spends the duration of the scene gloating, and then condemning Clancharlie to torture and death via an iron maiden (an iron cabinet with hinged lid and spike-lined interior) while Gwynplaine is mutilated by comprachicos, a gypsy group who malform and deform children to later sell as mountebanks, pages, court fools, and clowns. Though the iron maiden was a fictional device (since no proof one was ever used to torture actually exists), the imagery of the iron maiden closing on Clancharlie as he laments the poor fate of his child is really what reinforces The Man Who Laughs as a prototypical (yet atypical) horror film, ripe with expressionistic and political undertones. Throughout the scene the king is laid bare as a cruel and petty tyrant, and that Barkilphedro is making the king a fool, as his own machinations for power and influence motivate the advice he gives to everyone. To this end, the intertitles clarify, “all his jests were cruel, all his smiles were false.”

This relationship is carried over to the latter part of the film, with Barkilphedro intrusively influencing Queen Anne (Josephine Crowell) and blackmailing the Duchess Josiana (Olga Vladimirovna Baklanova) to fit his desires for mastery in the Royal Court. Barkilphedro can possibly be seen as the original Gríma Wormtongue, always plotting within plotting, steering the course of major events determining fates of countries to suit his own ends; though unlike Gríma, Barkilphedro has no greater master. This type of character was not uncommon in Victor Hugo’s novels (from which this film is based) and Hurst was no stranger to playing such roles, such as Sir George Carew in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Frollo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Dichotomously, whereas the first sequence of the film is a spotlight on the facade and manipulation in the highest ranks of social order, when we catch up to the young Gwynplaine (our protagonist) being carried away to a ship of comprachicos fleeing England, the harsh emotional reality of the lowest ranks of social order are unceremoniously put on display. The scene is full of roaring wind battering people about in the depths of a blistering snow storm. The murky textures of the ship and its people are grossly emphasized against the pale landscape. To try and improve their odds against capture, the comprachicos discard Gwynplaine on the shore and abandon him to the elements. As Gwynplaine struggles through the harsh environment, superimpositions of skeletons of those hung or imprisoned and left to decay overlay with a ghostly resonance, as if every step that he takes brings him closer to his own death.

As the night grows darker, the blizzard continues to roar, Gwynplaine soon discovers the body of a frozen woman, clutching onto her infant child who just clinging to life. In an attempt to save the child and himself, Gwynplaine rushes with the child into the darkness, constantly being hounded by large crows waiting to feast on the boy’s eventual corpse. The fading light, as if in a fog, and the fatalistic tone in which we find the characters is quite similar to the snow-covered final act of Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980), or much of Tomas Alfredson's Let the Right One In (2008); what is frightening is not just the evident dangers, but those lurking just out of your periphery. They come to a small village where a carney doctor and a self-proclaimed philosopher, Ursus (Cesare Gravina), take in the mutilated boy and the baby girl, to which he diagnoses as blind. This sequence perfectly represents the struggles and pain that Gwynplaine will endure throughout his life depicted in the film, and the kinds of people to whom will offer his only solace.

The Man Who Laughs takes a much more direct turn for the tragic instead of the horrific when we cut to years later, Gwynplaine is now a clown in a traveling carnival with his adopted family of Dr. Ursus, his blind beloved Dea (Mary Philbin, in one of her final and most notable film roles), and their wolf Homo (Zimbo). This character dynamic and setting is almost the antithesis to The Cabinet of Dr. Calagari; whereas this doctor sheltering Vedit’s character is the most empathetic of all the film’s characters, becoming a father figure to both Gwynplaine and Dea. This decision helps foster their feelings for one another throughout the years with only good intentions as a motivator. This distinction further accentuates this film’s previous points on social structure and class disparagement with the poor carneys being the ones who truly accept Gwynplaine as a human. This “demonized/deformed outsider” motif is the most important aspect of this film, which has been replicated in many subsequent works even outstripping the horror genre by the likes of David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980) and Peter Bogdanovich’s Mask (1985). Though this isn’t the first film to attempt this, it is the first major work to not have their outsider be villainous in some way.

Such introspective and societal commentary would grow from being a novel experiment to a constant theme running through horror filmmaking up to the present day. Though there are many exceptions to this, horror moviemaking became the best breeding grounds for such discourse due to their exploitive nature. Their relative low budgets and wide underground audience appeal would allow conversations about sex, race and violence to go by relatively unchallenged, hitting its peak during the 1960s drive-in boom. However, before the freedom of the 60s and 70s, Hollywood still majorly held sway over the release of films, mainly due to the production companies owning their own theaters until the Hollywood Antitrust Supreme Court Case dismantled the system in 1948. The Man Who Laughs was the perfect blend of exploitation and art for the filmmakers of the time, inspiring a humanist push in horror film to include legitimate drama beyond surface-level scares.

The most significant example within the film that relies on melancholic elements to evoke a true sense of horror within the narrative is the ending sequence with a massive mob of people chasing Gwynplaine after he rejects his noble appointment by the Queen, in turn rejecting a marriage to the treacherous Josiana (who now is the owner of the Clancharlie Estate) who had privately shamed him for her own bored amusement. In part to Barkilphedro’s taunting, the royal court is up in arms and rabbles for Gwynplaine’s life. Though Frankenstein would similarize this sequence at the climax of its arc, it was forced by the studio and the Hayes Production Code to kill off the monster due to its unnatural existence. This actually would become a requirement of all subsequent monster movies, regardless of the motives of the creatures, and in turn hurt the allegorical intentions of many of these classic works for the next two decades. The Man Who Laughs was the one film that slipped through this requirement, ending with Gwynplaine, Dea, Ursus and Homo fleeing on a ship to Europe, with the gnashing crowd unsatisfied on the shore amidst the thrashing waves. The imagery invoked is full of grandiose set pieces and massive amounts of extras, playing up the scale to add to a sense of epic triumph in the face of a collective immorality. The average human is the true monster here, even tearing down the class disparagement to include all walks of life in the mob, and the film doesn’t attempt to make the determination parabalistic. Which is more intriguing by way of the original novel concluding with Dea dying and Gwynplaine’s suicide by drowning while the movie ends upbeat and hopeful.

Gwynplaine suffers at the hands of the bigoted mob and the sardonic whims of the noble elites, but in the end, he triumphs and escapes, denying his tormentors their unjust satisfaction. The horror is more anthropological than explicit, and such a treatment openly inspired Tod Browning to make the exact same argument in 1932. In roughly the same kind of setting, Freaks would manage a shockingly graphic tale with such little remorse and stark realism that it stands to this day as the last of the greatest expressionist-inspired horror films of the early 20th Century. Though its unabashed attitude about incorporating legitimate carnival freaks and crimes unredeemable on both sides with no clear morality winning outright is what not only sunk the film as a critical and commercial failure at the time of its release, but also effectively destroyed Browning’s illustrious career.