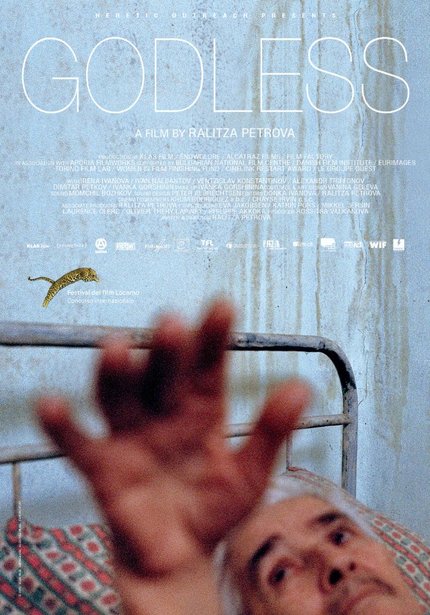

Toronto 2016 Review: Bulgarian Drama GODLESS Depicts Moral Decay in an Eastern European Dystopia

Ralitza Petrova, an emerging filmmaker from Bulgaria, unveiled her powerful debut outing Godless recently at the Locarno Film Festival, where she ended up standing in the spotlight and holding the Golden Leopard award. She thus joined the ranks of talented newcomers initiating a curiosity of future prospect of their careers and how their body of work will eventually evolve.

Two years ago, Maya Vitkova, another Bulgarian debutant, appeared on the festival circuit introducing her surprisingly ripe feature-length debut Viktoria. Vitkova touched upon a myriad of subjects related to motherhood and raising a child in a totalitarian state, recalling the not so distant past of Bulgaria. Petrova follows in Vitkova's footsteps in terms of subject matter, while displaying exceptional talent, vision and personal style.

Similarly to Vitkova, Petrova does not cross beyond the borders of her homeland in the rather grim and raw story Godless unfolds to be. Despite the title, explained towards the end of the running time, Godless is a hopelessly unreligious film, although a subtext of spirituality scratches the theme, but in a fairly different manner than what could be expected.

It has become almost a stereotype of how the cinema of Eastern Europe, particularly the geo-political region of the former Soviet bloc, deals with its past still echoing in the present. The past that remains painfully etched in the nation's D.N.A. has bestowed generation after generation as though it were, in a religious context, a hereditary sin.

A sort of prologue opens the film, foreshadowing one of the main topics to be corrosive corruption. A cryptic epilogue, or coda, tops off Godless. In between, Bulgaria is looked upon through the lens of home care worker Gana (the perfectly cast Irena Ivanova). Unlike last year's Czech Acaemy Award submissionf or best foreign-language film, the dramedy Home Care, revolving around a similarly employed protagonist in like-minded space, Godless unpacks a full-on and almost tactile existential pressure and despair, a total depresso fare, the type of Eastarn European social drama that the region has became notorious for.

Short of any virtuous intentions and idealism the Czech counterpart harbors, Petrova paints her protagonist as an anti-heroine taking advantage, if not outright exploiting, her clients, most of whom suffer from various ailments related to dementia. The social group that is being victimized offers easily reachable opportunities, turning the viewing experience even more gut-wrenching and harrowing, as the Austrian iconoclast Ulrich Seidl has shown in the infamous scenes from the geriatric ward in Import/Export . Petrova does not add more oil to the fire, although the motif of the perils of old age bears undoubtedly a much wider and more universal statement in Godless.

Petrova embodies the disillusion of economically and socially limping Eastern European countries frozen in post-industrial gloom in a tight grip, and distills it illustriously through the character of Gana, equally archetypically as well as psychologically chiseled. Meanwhile, Ivanova's striking performance, based on passiveness and blank stares, channels the ultimate resignation. The nurse's anti-heroine image thus stems from the choice to succumb to the prevailing marasmus.

Another Czech film, We Are Never Alone by Petr Václav, tackled the very same condition through its male characters, who capitulated in favor of passiveness and wallowed in nihilism, more unwilling than incompetent to act against it. The thematic overlapping of both films (and several others) only confirms the shared universal and alarming endemic condition across the nations.

In the desolate setting of Godless, the answer does not sound as misplaced. On the contrary, the terse reply, maybe one of the most austere yet civic celebrations of the triumph of human will, revives Gana´s numb senses the same way Yoan's (Orthodox Christian) choir does. The transcendental power of angelic voices reminds the protagonist of things beyond the murky cesspool of poverty, sickness and despair.

It is this kind of spirituality, freed from the shackles of organized religion, that eventually awakens a tiny piece of joy in Gana, the same way that the disturbing corporeality of Rúnar Rúnnarson's Sparrows is overcome by the protagonist singing and Iceland's pristine vistas.

Even though Ivanova has the largest amount of screen time, the director reserved a space to smear corruption in a scathing portrayal of the country's rotten political system, where people who are supposed to protect and assure justice are basically raping it on running basis without frowning a brow. The director´s indictment is more urgent, as the disintegration that eventually affects the whole society, not only working class of a provincial town, runs to the upper echelons of the apparatus.

The art production and locations pungently invoke the general atmosphere of moral decay and omnipresent daily misery through a bare bone aesthetics that could be simply described as Eastern European dystopia. A necrotizing post-industrial town past its prime, riddled with concrete chunks of the Communist era architecture dilapidating along washed out interiors of decades ago form an overwhelming visual cacophony of disintegration, forsakenness, hopelessness and dehumanization, sprinkled with a suffocating spleen.

A similarly socially-conscious venture was explored in The Lesson, a poverty porn thriller by Bulgarian tandem Petar Valchanov and Kristina Grozeva. Although poverty is still a factor in Godless, not as a catalyst but as a mundane reality, Petrova shifts the lens to deliver a moral thriller in the frame of a social drama, wielding the minimalistic and raw style to a piercing and lasting effect. It may seem that Petrova beats vigorously the very same drum as her predecessors did, but she makes sure to bring her own notes.