Fantastic Fest 2016 Review: The Unbearable Lightness of TONI ERDMANN

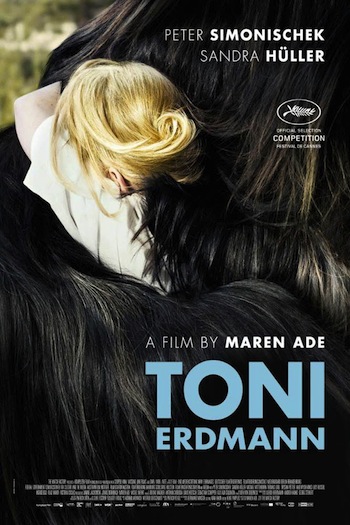

German filmmaker Maren Ade's third feature, Toni Erdmann, about an estranged father connecting with his adult daughter in increasingly unorthodox and aggravating ways, garnered glowing critical praise when it premiered in competition at Cannes this past spring.

While there is something to be said about the film's truly madcap and increasingly absurd multilingual clusterfucks - and they are perhaps the most potent and precise of any Palme d'Or nominee in years - those that know Ade's previous films (The Forest for the Trees, Everyone Else) should also expect a work that is achingly human and nuanced, working marvelously as both an intimate and awkward study of a father-daughter relationship and as an immersive look into the corporate politics of post-wall Europe. Indeed, it is in the way Ade balances these tones where the true genius and mastery of the film lies.

Apologies then if that headline was misleading. It was just too good to pass up.

The father in question is aging elementary school music teacher Winfried (Peter Simonischek). When not at school or teaching piano at home, he spends time with his dog and pulls pranks on unsuspecting delivery men. His daughter, Ines (Sandra Hüller), a thritysomething who works for a consulting firm, and is currently on a long term assignment in Bucharest with an oil company that needs outsourcing. A brief trip home for her birthday (or, well, early birthday) shows the massive rift between not only Ines and her father, but her whole family. Rather than small talk with relatives, she opts to stay in the garden, and even fakes a few phone calls. In Germany, at home, she is a stranger in a strange land. When she is asked about her life, she talks about moving up and on to Shanghai. She lives in an international world, far from these quiet older folks who sit and sip wine.

In an misbegotten attempt at reconnecting with Ines, Winfried shows up in Bucharest, first appearing in the lobby of a hotel where Ines is having a meeting. Sunglasses up, he carries a paper and a set of novelty gag teeth, yellowish and beastly, giving the already ogre-ish man an overbite. These teeth we will come to know as his comfort, his guard, his greatest weapon and asset in the fight to make his daughter less serious.

After a weekend putting up with his antics, Ines believes her father has gone back to Germany, only to discover in what has to be one of the sweetest-sourest reveals in all of modern cinema that he's still in town, or rather Toni Erdmann, life coach and consultant, is in town. Sporting a black suit, those garish set of teeth, and raven haired wig to cover up his gray haystack, Toni haphazardly edges his way into Ines' life at home, at work, and at the club. Her tolerance for his childish antics is low, but in the presence of her boss, her friends and lover, she has but no choice to play along, or else totally breakdown and embarrass herself.

It is at this point in the review where I must be careful of how I talk about the film. An increasingly labyrinthine unraveling of emotions and histories, Toni Erdmann is full of some of the greatest cinematic surprises of the year and I dare wouldn't spoil the experience for you. So I fall into general absolutes and film aesthetic speak.

A work of realism through and through, the actions characters commit fall under such significant awkwardness that they find life's inherent absurdity, making for an equally gut-busting and somber affair. Indeed, these sensations swing within several breaths of each other throughout the film's 162 minutes. And if you did a double take on that running time, if you are fascinated by, or even like these characters, that will mean nothing to you. Ade's seemingly effortless ability in handling tone is impressive beyond a doubt, while Simonischek and Hüller's performances are some of the best of year.

Ines, like her father thinks her to be, is a serious woman. But in the corporate world she exists in, she has to be to survive. The film's depiction of sexism in the work place is plain, matter-of-fact, and thus all together scathing. And yet Toni Erdmann is not a judgmental work in the slightest. Ines screams at her father, questioning his sanity, and indeed, we do, too. But we don't despise him for his behavior, however inappropriate it may be. To know Winfried is quite simple: He is a sad, lonely and genuinly silly man, the kind that performs weird mutations of jokes you would play on your five-year old. The major question of the film is whether or not Ines and Winfried can find some common ground, even just for a moment, and see each other for the people they actually are, not the people they expect each other to be.

Ines, like her father thinks her to be, is a serious woman. But in the corporate world she exists in, she has to be to survive. The film's depiction of sexism in the work place is plain, matter-of-fact, and thus all together scathing. And yet Toni Erdmann is not a judgmental work in the slightest. Ines screams at her father, questioning his sanity, and indeed, we do, too. But we don't despise him for his behavior, however inappropriate it may be. To know Winfried is quite simple: He is a sad, lonely and genuinly silly man, the kind that performs weird mutations of jokes you would play on your five-year old. The major question of the film is whether or not Ines and Winfried can find some common ground, even just for a moment, and see each other for the people they actually are, not the people they expect each other to be.

It's saying something to Ade's abilities as a storyteller that she can create such a nuanced, complex and uproariously funny film about a father and daughter while also addressing the changing tides of the European Union and the washing of culture. Indeed, the most telling line in all the film may be Ines off-hand comment about Bucharest having Europe's largest mall, but how no one has any money to shop there. The city we see is mostly the insides of hotels and offices, resort spas and roof decks. We are in no place. A corporate place. A place free of history and full of promise. A clean and stagnant place. When Ines or Winfried interact with the locals it is often awkward and embarrassing. The film is in no way overbearing with its discussion around economic development and the sort of capitalist version colonialism that can come with it. Like everything in the film, these passages are rich and strange because they are presented in the light of everyday where we are all just trying to understand each other a little more if only to just understand ourselves a little more.

Ines' struggle with the functions of being a corporate human is potent pathos, resulting in a breakdown that then offers up what is the film's greatest executed sequence, one involving a lot of non-sexual nudity and a folkloric Bulgarian character. Did I go to far into spoilers? I better step back then.

After so much hype on the festival circuit, I am glad to join those who feel Toni Erdmann is something special. If there is a zeitgeist film for Europe today it is undoubtedly this one. But there is perhaps no higher praise than when my friend and colleague James Marsh said to me shortly after our screening "I could go ahead and watch it again right now." That then is the mark of truly fascinating, immersive and undoubtedly great cinema.