Roddy McDowall Gets Busted: An Exclusive Excerpt From A THOUSAND CUTS by Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph

I'm not the sort of person who is precious about my consumption of films.

For me, the recent hubbub surrounding the death of 35mm projection has largely been white noise that confuses the method of consumption for quality. However, if there is any argument that could possibly change my mind, it is sure to be found in the pages of the new book, A Thousand Cuts: The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies, by Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph.

Bartok and Joseph are both experts in the world of 35mm film collecting and exhibition. Bartok has an impeccable pedigree as the former head programmer and current general manager of the fabled American Cinematheque. He has also recently worked with the upstart US distribution label Cinelicious Pics, whose small but impressive collection includes Anurag Kashyap's Gangs of Wasseypur, erotic anime Belladonna of Sadness, and a number of other outré features past and present. Joseph finds himself among the collector community as one of its most respected members, as well as an archivist. Joseph is currently working on preserving and restoring the works in the Hal Roach/Laurel and Hardy library.

The authors and the publisher, The University Press of Mississippi, have graciously allowed us to share one of the most interesting and notorious chapters of film collecting history with ScreenAnarchy readers: the FBI bust of Roddy McDowall, star of the Planet of the Apes saga, and the subsequent harassment of many other high profile film collectors during the seventies.

In the chapter titled "An Expensive Hobby," Bartok describes McDowall's famed 1974 FBI bust that ultimately led to a Red Scare styled outing of print collectors from Rock Hudson to Mel Torme.

(All text courtesy of University Press of Mississippi.)

An Expensive Hobby

The best-known film collector in the early 1970s to run afoul of the FBI is no longer around to share his story. At the time, the elfin, instantly recognizable British actor with the wonderfully musical birthname of Roderick Andrew Anthony Jude McDowall was experiencing a career resurgence. Since 1968, when he’d played the sympathetic chimpanzee Cornelius in Franklin J. Schaffner’s epochal Planet of the Apes, Roddy McDowall had starred in three more films in the hugely successful series. The studio had left him out of the first sequel—the weird, dystopian Beneath the Planet of the Apes —but thankfully brought him back as Cornelius for the next, Escape from the Planet of the Apes. Even better, they reinvented his character as Cornelius’s rabble-rousing, revolutionary son Caesar, leading his people—or chimps—to freedom in Conquest of the Planet of the Apes and Battle for the Planet of the Apes. In the former he gets to deliver one of the series’ most memorable speeches: “We have passed through the night of the fires, and those who were our masters are now our servants. And we, who are not human, can afford to be humane. . . . So, cast out your vengeance. Tonight, we have seen the birth of the planet of the apes!” McDowall had become the actor most identified with the blockbuster series. In modern Hollywood parlance, he’d become “essential to the franchise.”

And the Apes films weren’t his only success: he’d also co-starred with Gene Hackman, Ernest Borgnine, and Shelley Winters in director Ronald Neame’s gargantuan, melodramatic, and hugely entertaining The Poseidon Adventure, still by far the best of the early 1970s disaster movies. It was, all in all, a remarkable career turn for a man who’d started thirty years earlier as a slender child actor in How Green Was My Valley, Lassie Come Home, and My Friend Flicka. McDowall was, in a word, cool. He’d even been brought back as yet another chimpanzee, Galen, in the Planet of the Apes TV series, for which 20th Century Fox and CBS had high hopes. It was one thing to be a working actor—McDowall had always worked, since he was barely six years old, and he’d continue working up until his death in 1998. But to work and be successful, that was a rich reward for any performer, and especially one who loved the movies and Hollywood as he did.

It was in fact his deep passion for films—not just his own, but those of his friends and coworkers—that brought him to the attention of the FBI in late 1974. McDowall had been doing business with two film dealers that the FBI was keeping a close eye on: indirectly, Roy H. Wagner (later an Emmy-winning cinematographer on shows like House and CSI, and interviewed separately for this book), and directly, a notorious character named Ray Atherton. The Chicago-born Atherton would later appear briefly in director John McNaughton’s savage 1986 cult hit Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. He played a pawn-shop owner who kills a man by breaking a television set over his head. It was apparently typecasting for Atherton. He’s been described by former employee Ted Newsom (who directed the delightful documentary Ed Wood: Look Back in Angora) as “perhaps the foulest-mouthed, most racist, anti-Semitic, misogynistic, hateful fucker I have ever met.” Newsom, who has a way with words, goes on to say that Atherton would “go over to the liquor store across the street nearly on a daily basis . . . 9:30 AM or 10:00 or 10:30. More often than not, he’d be so totally hammered by 1:00 PM that he’d either go on a rant, at which point you couldn’t work at all, or he’d segue into nappy time, and just pass out with his head on his desk. It was an impressive sight. He probably weighed 350 or 400 pounds, six foot two or six foot three, bald with a Friar Tuck fringe of hair. Horned-rim glasses.”

Collector Mark Haggard, who knew Atherton well, says that he later did a brisk business selling documentaries on Church of Satan leader Anton LaVey, including Speak of the Devil (1995), which Atherton executive produced—and also, perhaps not coincidentally, had a church member working on his staff. “It’s all bullshit,” Atherton told Haggard one day about LaVey and Satanism. “But it interests people, and it sells a lot of videos.” Among his other offenses (and there were apparently many), Atherton ridiculed a group of Muslims that he regularly did business with. According to Newsom, “at least four times a day, they got out their prayer rugs, and bowed to Mecca, and did their business. Ray at one point stole one of their prayer rugs. He was drunk, I’m sure. Calling attention to it so everybody’d watch through the window, he went down to the parking lot and kept throwing it into the air, crying, ‘Fly, motherfucker, fly!!’” All in all, a bizarre character for someone of McDowall’s reputation to be doing business with. But Atherton had what McDowall and all other collectors desperately wanted, and that was access to prints.

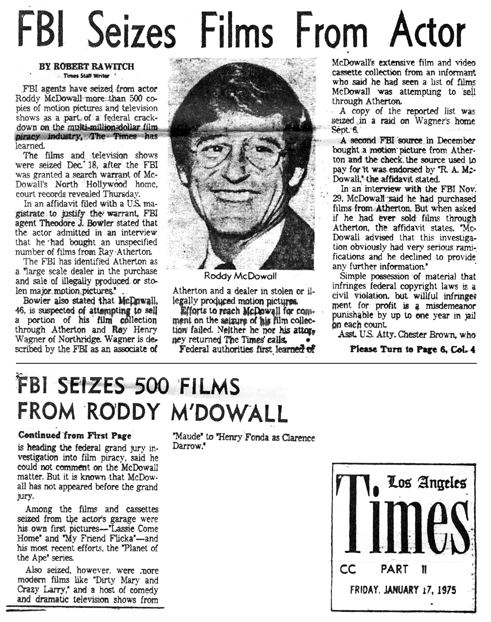

According to an article in the Los Angeles Times, in November 1974, the FBI requested a sit-down interview with McDowall about his supposed dealings with Atherton. Apparently, an unnamed informant had seen a list of films that McDowall was attempting to sell through Atherton and his associate Roy Wagner; a copy of the list was seized in a raid on September 4 at Wagner’s home. During the initial FBI interview, McDowall admitted that he’d bought films from Atherton in the past, but when he was asked if he’d ever sold movies through Atherton (potentially a more serious crime), McDowall “declined to provide further information.” Sensing they had a major target in their sights, the FBI and Assistant U.S. Attorney Chester “Chet” Brown moved in for the kill.

Of all the behind-the-scenes players in the early 1970s “film busts,” the most active on the law-enforcement side—and the most opaque, personally—was Chet Brown. Looking back, he may not have been the main driving force behind the busts—certainly the MPAA, working on behalf of the studios, was pushing for the crackdown to protect their copyright interests—but Brown became the main figurehead, at least for a while, and much of film collectors’ and dealers’ ire was (and still is) directed at him. Roy H. Wagner, who was targeted in the Atherton–McDowall case, describes Brown as “an egomaniac” and adds, “He was so fascinated that he was doing something with the movie business. He was talking about the movie stars that were going to befriend him because he was going to save the movie business.” Collector and electrician Peter Dyck, who was also targeted in the highly publicized film piracy arrests in 1975, still becomes enraged at the mention of Brown’s name: “He hated film collectors. It’s like in Patton, when General Bradley says to General Patton, ‘I do this job because I’ve been trained to do it. You do it because you love it.’ Chet Brown was the same way.” Even James Bouras, who was working for the MPAA at the time, says that Brown “obviously had ambitions of what he was going to do after he left the U.S. Attorney’s office.”

These judgments, many of them from collectors and dealers who felt personally singled out and harassed by the feds and the Justice Department, are obviously a bit biased. On the flip side, Brown’s former boss at the time, U.S. Attorney Dominick Rubalcava, told me that Brown was “hardworking, enthusiastic, and focused. Chet was a hardworking guy. Again, in the U.S. Attorney’s office, once you develop an expertise you get handed those cases. Some guys like doing bank robbery cases. Some like drug dealing. Some guys like fraud or IRS cases.” Chet Brown obviously had a taste and talent for film piracy cases, and for several years his name appeared repeatedly in connection with film raids in the Los Angeles area. The most high-profile of these was directed at Roddy McDowall.

On December 18, 1974, the FBI, search warrant in hand, barged into McDowall’s home in North Hollywood and seized some five hundred film prints and videotapes (the number was later revised to over a thousand videos and one hundred sixty 16mm prints.) The raid, which appeared in the Los Angeles Times a month later, on January 17, 1975, and was picked up nationally by news services, was a massive personal blow to McDowall’s career, and by far the biggest “get” in the FBI’s and Justice Department’s war on film piracy. If they were trying to send a warning to other collectors and dealers, then the message was delivered loud and clear. Even now, forty years later, a number of collectors and dealers mention the McDowall raid as a watershed moment that kicked off a general wave of fear and paranoia that lingers in the collecting subculture to this day.

From the FBI’s perspective, the raid was a great success. According to an internal U.S. government memorandum dated July 1975, the “recovery value of pirated motion picture films . . . and miscellaneous equipment which were seized from Roddy McDowall, prominent motion picture actor, during the execution of a search warrant at McDowall’s residence” totaled $5,005,426. The memo goes on to state that “most of his collection was pirated.” Among the films seized were prints of McDowall’s own movies Lassie Come Home, My Friend Flicka, and several of the Planet of the Apes movies. How the feds arrived at the astronomical valuation for McDowall’s collection is a good question. Even at the height of the underground film market, $5 million seems more like wishful thinking than reality. As a benchmark for comparison, dealers Ken Kramer and Jeff Joseph were selling prints around the same time to Playboy magazine publisher Hugh Hefner for the premium price of $500 for a black-and-white movie and $1,000 for a color movie. Even assuming all of McDowall’s films were color and that he could sell them for the same high price, that’s still only 160 16mm prints x $1,000 equals $160,000. The value of the videos is another matter, and in retrospect it may be those that the studios and the feds were most alarmed by, since it was apparent that McDowall was taping movies off TV and also transferring his prints to video. Ironically, in just a few years, your average American consumer would have just about the same number of videos taped off TV on their newfangled VCR or Betamax machines, maybe not quite as many as film buff McDowall—but nobody broke down their doors with a search warrant.

What happened next is not Roddy McDowall’s finest moment. Faced with prosecution and a potentially crippling blow to his career, he rolled over and named names. Even using the term “named names” is politically charged, since it brings to mind Hollywood professionals informing on their coworkers to the House Un-American Activities Committee during the communist witch hunts of the 1950s. McDowall’s situation was very different: he was the target of a legal investigation aimed at rooting out film pirates in Hollywood. To call McDowall a “pirate,” though, as the government’s internal memo implies, is a stretch—like many, possibly the majority, of film collectors Jeff and I interviewed, he’d turned to occasionally selling prints from his collection. Here he was, publicly linked with a guy like Ray Atherton, a Muslim-baiting, anti-Semitic loose cannon. Put yourself in McDowall’s shoes, and what would you do?

What follows is an abbreviated transcript of McDowall’s confession to the FBI, heavily redacted, with many names blacked out. It’s a fairly remarkable document, often poignant in describing his childhood and career. It clearly shows his enormous, abiding love for the movies, and also the enormous stress that collectors were put under when they found themselves caught in the government’s legal net

"February 14, 1975,

Los Angeles, California

I, Roderick Andrew McDowall, voluntarily appearing, hereby make the following free and voluntary statement. . . .

Personal History

I was born in London, England, on September 17, 1928. I became involved with modeling when I was six years old and when I was about nine or ten years of age, was hired for my first movie role. By the time I was twelve years old, I had performed in about eighteen films.

In 1940, my father sent my mother, sister and I to the United States because he felt we would be safer here with my mother’s relatives and he was contemplating re-entering military service in England. Shortly after arriving in New York, through a strange set of circumstances, I was hired for a role in the movie How Green Was My Valley. This film subsequently won nine Academy Awards and made me a child movie star.

As long as I can remember, I have been totally involved with films and the movie industry. My mother used to take me to an old silent movie theater where I became familiar with the performances of many of the silent movie stars. As my acting career progressed, I met some of these silent stars in person and from these associations I became extremely interested in the history of film and stage.

I started my film collection during the mid-1960s as a result of my fascination for old movies and my interest in observing the progression of many actors and directors, starting with their first films up to their current work. I also had become interested in lost films and wanted to prevent films from becoming extinct, if possible. Also, studying these films helped improve my acting skills.

My film collection has always been a hobby for me. These films, mostly 16 millimeter with the exception of The Ballad of Tam Lin and some of the Errol Flynn estate collection of films which I purchased, have been an extraordinary delight for me and I feel that they contribute to film history.

At the height of my collecting, I believe I possessed about 337 films at one time. However, because as a collector I would sell, trade and purchase films, it is impossible to determine the total number of films I may have had in my possession. . . .

I decided to place a portion of my films on videotape cassettes because of the ease of storage, space saving advantages, and the longer life expectancy of videotape as compared to film.

I decided to sell my collection for the following reasons:

Many of them I had transferred onto videotape, some were films that

I no longer had any interest in, and I knew that others would be playing frequently on television and could easily be videotaped. My films were sold for the same price for which I had purchased them; however, because I kept very few records of such purchases, this determination depended somewhat on memory. . . .

Prior to the current investigation, my understanding of the copy- right law consisted of believing that as long as I did not show my films for profit, as long as I did not commercially attempt to earn money from showing them, it was not a violation of the copyright laws. . . .

I do not recall knowing of a studio ever selling their films to private individuals who are not in some way associated with the film industry. However, I was never in a position to be caused to dwell on how individuals outside the film industry obtained films. My life has been almost totally involved with films and the film industry both at work and at home, and meeting people who had films and film collections was an everyday occurrence for me.

Individuals From Whom I Have Purchased Films

Regarding the individuals whom I thought were collectors from whom I recall having purchased films, I can provide the following information concerning my association with them:

I became acquainted with [name redacted] in New York City (telephone [number redacted]) while I was living in New York City. I do not recall how we first came in contact with each other; however, I met him personally only once. At that meeting [name redacted] was desirous of selling a block of films, 26 in all, for a bulk sum. I was anxious to possess one of the films, so I purchased the block of films he was offering for sale. . . .

I do not recall how I first came into contact with [name redacted] from Tonawanda, New York. I believe I purchased and traded films with him, the last purchase according to my records being in 1971. This trans- action consisted of my purchasing The Magnificent Ambersons, Camille, Applause, and She Done Him Wrong. I paid for these films with a check in the amount of $705.00. . . .

I do not recall how I first made contact with [name redacted], Chicago, Illinois, but it was some time during the 1960s. . . . I purchased Planet of the Apes, and according to my records, Escape From the Planet of the Apes from [name redacted] after he had moved to Los Angeles, and I would assume these films were delivered to my residence in person; however, again, I cannot be sure. . . .

As I review the list of films which were seized during the execution of the search warrant on my home, I can provide the following information as to the persons from whom I obtained these films:

Giant —Given to me by Rock Hudson

Breakfast at Tiffany’s —Given to me by Richard Shepard

. . . .

Persons With Whom I Traded Film

The following individuals are persons with whom I recall trading film:

[name redacted] of Thunderbird Films, do not recall which titles.

[name redacted] do not recall which films.

[name redacted], I also may have purchased films from this man; however I cannot remember for sure. I met him while making the Planet of the Apes feature movie at the studios. I did not care for him and soon discouraged his contacting me regarding my film collection.

Film Collectors

I am personally aware of the following individuals possessing film collections themselves:

Arthur Jacobs (deceased)

Rock Hudson

Dick Martin

[Name redacted]

Mel Tormé

[several names redacted]

. . . .

I have no partners in the business but the business does have a treasurer and a vice president. It is a corporation which was formed in California in 1972. I used corporation checks to purchase films in which I had appeared and to pay for videotaping of programs or films in which I had appeared such as segments of the Hollywood Squares episodes, Planet of the Apes, etc.

Escape From the Planet of the Apes was produced in 1971. As I recall, when I learned it was to be shown on television, I made arrangements with [name redacted] to tape it from television. However, the television version of the movie had part of the final scene edited. This scene, a scene in which I get killed, required some very difficult and painful acting in that I was required to make a terrible animal noise which was extremely horrifying. The television version did not portray a portion of this scene and I was desirous to have the scene in my collection; therefore, I think that was the reason I purchased the complete film from [name redacted] in 1974. I desired a print which had the final scene intact."

Obviously, it’s the final passages of the confession that are the most controversial, and the most difficult to read. It’s one thing for McDowall to admit to his own collecting and videotaping, and even to name the dealers from which he purchased prints. It’s another to willingly offer up the names of friends and colleagues like Rock Hudson, singer Mel Tormé, comedian Dick Martin (of Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In fame), and even the deceased Arthur P. Jacobs, producer of the five Planet of the Apes films that had made McDowall a major star again. (In 1973 Jacobs had suddenly died of a heart attack at age fifty-one.) Even though Jacobs was no longer alive to be concerned about the FBI knocking on his door, naming him (and what possible good could it do the FBI, since he was dead?) seems like an act of ingratitude at best on McDowall’s part.

As far as McDowall’s legal troubles with the FBI and the Justice Department, the confession did the trick. On June 4, 1975, the St. Petersburg Times and other news outlets reported that McDowall had been cleared of all film-pirating charges in connection with the raid on his home. Further, “Assistant U.S. Attorney Chet Brown said the government concluded that McDowall committed no wrongdoing.” Given the level of scandal we’re now used to from celebrities, McDowall’s troubles seem like barely a minor kerfuffle, but it was obviously a deeply scarring experience for McDowall, who dropped out of collecting altogether. To this day, internet users routinely refer to him as a “fink” for his confession—a sad judgment, perhaps, for an actor who gave so much to his profession.

Did it have any repercussions for him among his Hollywood friends, especially those he’d identified to the FBI? Apparently, there were no further arrests or film seizures made based on the names McDowall provided (although several names have been redacted). When I mentioned to Hollywood Reporter journalist and Turner Classic Movies host Robert Osborne that McDowall had named Rock Hudson to the FBI, he was genuinely surprised. Osborne, who knew both men well and even catalogued Hudson’s private film collection, said that if Hudson had been aware of McDowall’s confession, he never let on, and that this was “all well-known information about who was a collector and who wasn’t.” Osborne continued, “I don’t think it was anything like the House Un-American Activities Committee. Also if you bought films from The Big Reel or something, they could have checks that you sent in to buy a copy of Gilda. I know that I was contacted at one time [by the FBI] and told it was against the law, but nobody ever asked to see my collection.” Roy H. Wagner, who was (and still is) understandably reluctant to speak about his experiences, given his later career as a cinematographer in the industry, confided to me, “I talked to Roddy McDowall about this years later, and to Mel Tormé, and they both said, ‘You were really set up [by Chet Brown].’” He paused, then added, “I did Hart to Hart with Roddy.” It’s a small industry indeed where two men caught up in an FBI film piracy dragnet wind up working together on Hart to Hart. Collector Tony Turano, who knew McDowall at the time of the film busts, said that “it broke [Roddy’s] heart to lose his films. Of course it scared the shit out of everybody that had films. All of a sudden everybody went underground, and nobody wanted to talk about owning films.” When I asked if McDowall stopped doing screenings at home after the busts, Tony replied, “Everything stopped. I never went to his house again. . . . Roddy had a beautiful film collection. He had beautiful prints. I guess he had the money to buy the best.”

And what about Ray Atherton, the prayer-rug-waving dealer who touched off the firestorm? In a stunning blow to the government’s much- touted war against film pirates, Atherton’s separate convictions on five counts of copyright infringement and one count of interstate transportation of stolen property (for prints of The Exorcist, Airport, The Way We Were, Forty Carats, and Young Winston) were overturned in October 1977 by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. As reported in Variety, “Driving a knife through the heart of the prosecution’s theory, Judge Shirley M. Hufstedler said the copyright convictions were wrong because the government failed to negate the ‘first sale’ copyright doctrine which might shelter Atherton’s trades. And in a second stab, the court said the government failed to show that the specific 16mm print of The Exorcist was worth the $5000 value that it would bring under federal interstate transportation laws . . .” (The value placed on the Exorcist print brings to mind the astronomical price-tag of over $5 million the feds put on McDowall’s collection.)

After that, Atherton continued in his dodgy trade in film and video unabated. According to his former employee Newsom, he married “a wife who he couldn’t stand. . . . He was utterly dismissive and abusive to his family and in-laws when they weren’t present. When they were around he came off more like Ozzie Nelson.” Just to show that not everyone is all bad all the time, Atherton and his wife adopted a little girl whom he “adored,” according to Newsom. “The earthquake in 1994 apparently terrified his little daughter, who was about two or three. Traumatized her. So he moved to Las Vegas, which he assumed was safer.” When I asked what became of him in later years, Newsom chuckles: “Ray had huge tax problems. He didn’t give a shit about the IRS. I remember once that this huge fat man was doing this exuberant dance, because he’d gotten a fifteen-thousand- dollar check—an advance for some project he’d proposed. I was happy because I knew I was gonna get paid that week. . . . But within two days of that, he was flat-assed broke.” Six months after relocating to Vegas, he “simply dropped dead of a massive heart attack,” Newsom recalls. “He was only about forty-eight, I think. But he was 150 pounds overweight. He would go through a bottle of goddamned rum in half a day.”

In something of a final coda to the film-related hysteria that swept up Roddy McDowall, Ray Atherton, and many others, on December 14, 1986, the Los Angeles Times, in a tiny article barely four paragraphs long, re- ported that “a former federal prosecutor in Los Angeles has been charged with obstruction of justice and perjury in connection with an investigation of a fraud ring.” The former prosecutor was none other than Chester “Chet” Brown, Assistant U.S. Attorney during the early 1970s film raids. Brown was “charged with advising witnesses to deceive the grand jury . . . and later lying himself when asked about his role in the alleged cover-up attempt,” related to a Pasadena-based fraud ring that provided false credit information about itself to get between $8 million and $15 million in merchandise. Although his later legal woes were completely unrelated to his role in the 1970s film busts, the news of Chester Brown’s fall from grace was, not surprisingly, met with unrestrained glee by the former targets of his and the Justice Department’s investigations; collector Peter Dyck, face nearly purple with rage, called it “poetic justice.” The collectors’ magazine Classic Images even reprinted the Times article about Brown’s indictment in the fraud case in case anyone missed it. Brown was later disbarred, and although he appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, Justices Rehnquist, O’Connor, Scalia, Kennedy et al. confirmed the disbarment, ending his legal career.

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Now Playing: SCREAM 7 Not So Scary, GHOST ELEPHANTS Not a Myth

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada