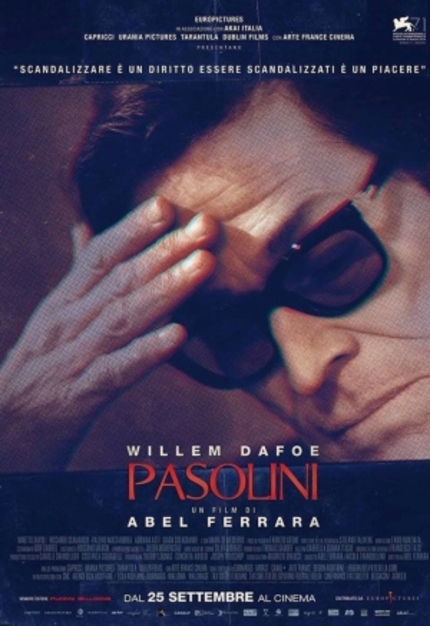

Lisbon & Estoril 2014 Review: Abel Ferrara's PASOLINI Hits Some, Misses Some

Abel Ferrara's take on Pier Paolo Pasolini's life (more than his career as a filmmaker, poet or philosopher) is the breed of biopic that seems modest and straightforward enough to make up for its obvious shortcomings. Its modesty comes from its focus (the final day in the filmmaker's life, and that day alone, as opposed to a larger-than-life, egomaniacal approach that would start in his childhood) while its straightforwardness reveals itself in the form of an 87-minute film that barely addresses his films - or even the themes present in those films. It's like Ferrara doesn't even dare to go into it, or doesn't see the point, so he goes with a more individual, humanistic-driven stance. Pasolini is less about Pasolini the artist as it is about Pasolini the human being, which doesn't make for a particularly brilliant film, but an interesting one nonetheless.

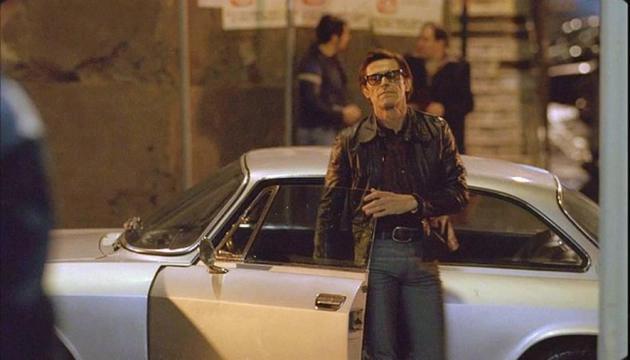

Whether this version of Pier Paolo is close or far from who the real Pier Paolo was is a whole other discussion, but Ferrara's Pasolini, as illustrated by Willem Dafoe's characteristically harsh, dense face, is a man who loves his mother and pasta (you need to embrace the clichés) in a way only Italian men seem to able to, battling censorship after finishing Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom and dealing with his own homosexuality, which, being 1975, entails dealing with Rome's underground circles and getting killed on a beach by a pack of homophobic, fascist kids. Again, it's Ferrara's take on what happened and how it happened, but it's one.

Pasolini isn't a great film - merely an interesting one. It isn't very subtle (Ferrara never is) in its attempts at grandeur accompanied by opera music, and even when it does try to go into those big philosophical and political ideas that defined Pasolini, through the means of an interview with a French journalist where the topic of moralism is brought up, it doesn't do much but graze them softly. In a way, Ferrara's ambition went into making it look artsy and pretty (which it does) and not so much into developing those big ideas. Thankfully, there's also Dafoe's brilliant presence weighing in, and he's a big part of why the film somehow works - even when Ferrara is stroking his own ego with overly long shots. Not that many actors could convey vulnerability muddled in such a bleak and rationally cold view of the world, but he does. I suppose when you've done sadist so many times before, a role like Pasolini must feel like home.

Besides Dafoe, the film's big attribute might be the way Ferrara blends the narrative, this day-long telling of a life that's about to end, with some imagination-driven vision of what Pasolini wanted to be his next film after Salò - a political/semi-mythological tale of two men who are en route from Earth to Paradise but don't seem able to get there. So as the older man stops to take a piss and looks back, he realizes, of course, that there is no such thing. These strange segments, which include a little trip to Sodom full of the absurdity and ecstasy of open-air orgies, help put the film together and make it precisely more open, shining a light on what might've been going through Pasolini's mind on that fateful day.

There's a sly danger with these types of biopics - that of expecting it to be some sort of unbiased, fact-driven portrait of someone who you assume you know because you know their work. That should hardly be the point of this film, and it hardly should be judged according to its historical accuracy. I'm sure there are plenty of documentaries on Pasolini's life and work, and you could probably get more information by simply going through his Wikipedia page (that will imply a lot of reading, beware), so the way I see it you have a lot more to gain by looking at it as merely a portrait - a personal, biased one - of a man who left an incomparable mark in film history by being the troubled, deeply flawed provocateur that he was (which is what Ferrara is interested in). Whenever the focus is on the man and not the man's life-work or who killed the man or whether the man was gay or not, Pasolini becomes a little more interesting.