Review: THE BALLAD OF NARAYAMA, Kinoshita Keisuke's Parable Of Age

The Ballad of Narayama (1958) is the first film of Japanese director Kinoshita Keisuke's season as part of the Melbourne Cinematheque program.

Running from February 13-27, his retrospective of conservative post-war films highlights a Japan in crisis, but through expertly mixing different genres he voids an iconoclastic approach, instead favoring traditionalism in a modernist setting, despite what effects that has on the society.

The Ballad of Narayama is essentially a parable of age.

This sharp melodrama tells the story of a remote village in Japan's feudal

period. With a drastic food shortage on their hands, a cruel but logical edict

states that anyone who turns 70 is expected to be carried by a relative

to the top of Mount Narayama to perish. The remarkable Tanaka Kinuyo plays

Orin, the protagonist, an old woman who has passed the required age and

struggles with her family and the village.

The traditional-style Kabuki play introduction praises traditionalism, as cold as it may be, and sets the audience's expectations. After the masked figure introduces the setting, the curtain pulls away behind him and we are immersed in a beautiful, studio-based village scene that is both artificial and heightened. The lyrical narrative weaves around the current happenings on-screen.

Kinoshita's patient and measured eye is reflected in the camera as it keeps a

respectable distance, never really investing in the emotions of the family it

highlights. The invisible describing force is more prominent than most features

of the film, as it was in Kabuki plays, and this voice acts as an internal

monologue for the players who cannot express how they feel. The artificial

scenery and village is surrounded by adages of age; blooming flowers, tombstones, and tepid skies that seem to taunt Orin.

Throughout

the film there are some splendid moments, such as when the scene drastically

changes and the foreground becomes shadow. The camera rapidly pans to the right

to a different background entirely and the story continues, truly a remarkable

and original transition, and it is this unique use of camera and lighting

effects that really enhance the film and showcases Kinoshita's superior skills.

The lighting and space he employs also denotes the anguish expressed by the

narrator, and most internal shots feel like the walls are closing in on Orin and

her gloomy predicament.

Despite the

visual intricacies, The Ballad of

Narayama is a contradiction of respect, as old age is presented

as a complex proposition that Orin must fend off. This lament is most obvious

in scenes where Orin interacts with her children and the other townsfolk, who

seem to treat her like a curse. The thought of counting down to an imminent

death fills them with guilt and hate and they often lash out.

For long

periods, traditional non-diegetic instruments take over the film. They

engulf these scenes in despair and longing. The Ballad of Narayama is about the journey and the destination as

the trek into oblivion is approaching and Orin goes through the stages of grief

beautifully; the mise-en-scene accompanies her emotional path.

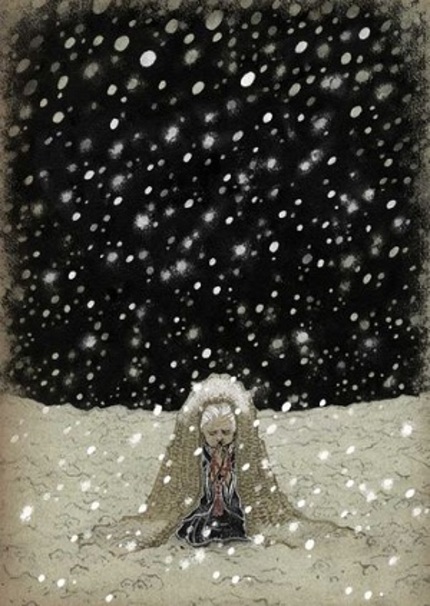

When the

inevitable does occur, the color palette and oppressive environment of the

stark and minimalist mountain harshness heightens the sense of impending

demise. The son carries Orin through to the peak of the mountain, and this is

when the film drastically changes, as the last ten minutes are sublime set pieces, simple yet shocking, and present some devastatingly chilling scenes that

will linger with you.

The Ballad of Narayama is a beautiful and woeful film

about coming to terms with death. The law imposed by the village council is not

particularly highlighted or attacked by Kinoshita, and his approach of a family

that must accept this fate is far more striking than a loaded message, as

people of this era would have had to have faced this sort of treatment in harsh

times.

Please

check the Melbourne Cinematheque guide for the rest of the films comprising

Kinoshita's marvelous season. I will return in March for the next season, the

films of Aleksei German and, especially, his film Trial

of the Road.