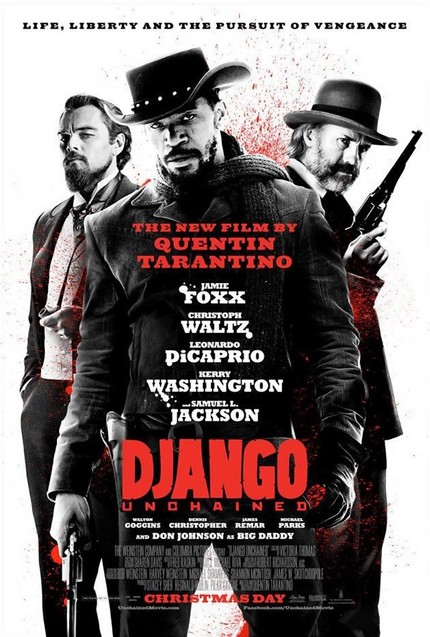

Quentin Tarantino Talks Race And Violence In DJANGO UNCHAINED

I was reading the Playboy interview you did recently and you were talking about how Calvin Candie is the first villain you've created that you really detested. What was it like creating a character like that?

Tarantino: It was interesting. I was a little bit worried. I had to be careful with him because one of the things that I've always like about my villains is that they don't think of themselves as villains. They all have their day in court, more or less. So I didn't want to hate him so much that I skewed it too much against him, or had everyone gang up against him, or put all the worst things in his mouth in order to make everybody hate him. But I couldn't hide my feelings, how much of a gargoyle I thought he was.

And that's one of the reasons I thought Leonardo was so terrific in the role and so good to work with. Because Leonardo thought this guy was as detestable as I did but when we were actually shooting it we didn't have the luxury of doing that [making him detestable], we had to take the guy for who he was. And so we invested in his home life, what it must have been like growing up on this plantation most of his life. Being the fourth Candie to run this plantation. And you get that a little bit when he talks about growing up on Candieland, surrounded by all these black faces for his entire life.

I remember when we did that scene in particular, that take in particular, after hating the guy for so long when he said that - the way he said it - I saw him as a little boy, actually, growing up in this weird bell jar that he had, and it did pose the question, "Can you blame a Borgia for being a Borgia?" I think you can blame a Borgia for being a Borgia but it's not that easy not to be a Borgia when you are a Borgia. And so it did finally get back to what I wanted, to that point where everybody has their reasons. They can be awful reasons but everyone has them.

We could really dig into that but the question I need to ask is about how this is the first film that you've made which is completely removed from cinema. It exists before films, so the characters are denied that frame of reference. I understand that it works for the characters but how did you get into that? Did you find yourself wanting to pull things in? You make cinematic references within the film but the characters are really forced, for the first time, to speak about the text instead of the subtext. How did you decide to abandon that comfort zone?

Well, it just goes without saying with doing a western. I think it highlights how, while it's easier to focus in on those tangents that happen in the other movies, they ultimately are kind of unimportant to the overall story. I don't have the luxury of writing a three page monologue talking about Superman's origins here as a metaphor for something else. None of the characters can be like that.

But frankly, though, Schultz is like that. He's not talking about movies but he's completely erudite and references literature and legend constantly throughout the piece. He has that. It's not about cinema this time but he's a very learned man who's constantly referencing his knowledge on all kinds of subjects. It definitely wasn't something I could fall back on but I don't know if I ever fell back on it before. I didn't have the luxury to weave that stuff in.

I guess what I mean is that there's no more perfect line than in Reservoir Dogs, "Motherfucker looks just like The Thing." It tells us who he is, it tells us where the world is, it tells us everything about everyone in it. Now the characters have to explain themselves more. It gives them monologues but not something that we can instantly relate to.

Well, everything is just much more historical. Like the comment I just made about Calvin Candie. He's not this character from this movie or that character from that movie, he's Louis XIV. Or he's Caligula. Or he's whoever. But it's a historical reference.

This movie - in a way that none of your others have been - throughout the process of making it was really present in social media both in good ways and, I think, in ways that could be very negative for you. And I'm curious about that process for you, when very early in the process the script is out there and then watching the casting process play out very, very much in public. As a filmmaker and as a creator I'm wondering what that experience is like for you and does it make it more difficult to put a deal together or bring a group of people together? How does it feel for you when you know the script is out there and you haven't even made the movie yet?

It's kind of a two pronged answer to that.

One, it doesn't stop the deal at all. We made a deal lickety split, as soon as I finished the script. Didn't stop anybody from wanting to be in the movie, nothing like that. So that's that.

Two, how do I feel about people reading the script? I want people to read the script! I worked my ass off on that, you know? I'm real proud of it, so I like people reading it. I have no problem with that. To me, when I write a script it's not a blueprint for the movie. It's meant to be a piece of literature that is an artistic work unto itself. So that's why I can't be cagey about it and stamp a bunch of crap on it that makes the reading experience less enjoyable when people read it. I want people to read it and enjoy it. I'm real, real proud of it. The movie's gonna be the movie, that'll come out later.

It's easy to get locked into thinking that everybody in the world has read your script when it gets leaked out like that, but no. A lot of people have read it but not everybody in the world. It did feel a bit like doing an adaptation of a novel on the New York Times best seller's list more than just a script that nobody has. But all that media - the social media and stuff - it doesn't mean anything to you if you don't read it. And I didn't read it. I'm not going to engage in any of that stuff, I'm making my movie.

I noticed that the movie had the cover of Fangoria, among others. And there are some very strong scenes, like the eye gouging scenes - which they cut away from in the version we've seen. Were there any particular censorship problems with this one and how did you approach the violence given that most of it is tied into slavery which, for a lot of people, is still a sensitive issue.

I didn't have any censorship problems in this movie whatsoever. Not in terms of censorship. The MPAA got this movie immediately. They actually gave an R rating to a more rough, more violent version than what we're actually presenting to the public as the released film. They got it right away. So I didn't have any problems with the MPAA whatsoever. I had more problems with the studio than the MPAA.

Basically what kind of happened was I could handle a rougher version of the movie than what exists right now. I have more of a tolerance for it. But I kind of realized when I watched that version of the movie with audiences that I was traumatizing them too much. I traumatized them. And I want people to enjoy the movie at the very end of it and after I traumatized them with the dog scene and traumatized them with the mandingo fight scene ... I cut their heads off. They grew another head and they continued watching it but they were traumatized and they weren't quite where I wanted them to be at the very end because of that trauma. And so, as rough as it is right now it's a little easier to take.

I guess piggybacking off that, I heard in the scene where they're whipping Kerry Washington you kind of traumatized yourself a bit and had to scale it back.

No, I didn't scale it back but I was affected by it. Yeah. I was operating the camera in one of those scenes and she got to me. She got to me. I was completely blind because my eyepiece was filling up with tears and I couldn't see anything anymore. That was a rough scene because of her performance. We weren't whipping her, it was all make believe, but because she went there and because we were dealing with what we were dealing with, everyone on the crew was feeling it.

It was where we were doing it at ... When you see that scene you'll see shacks behind her. Those were the actual slave quarters, where the slaves lived in those plantations. There is blood in that grass and there is flesh in those trees. And we felt the ancestors that had once walked there, we felt their ghosts and their spirits watching us do this. It was heavy stuff.

[Time is called]

Look, let me say something. Put your recorders back down. What I was actually trying to do with this movie in particular, when it comes to this kind of thing is this.

One, I wanted to tell an exciting story that dealt with a man who, on page one starts off as a slave and then gets all the way to the other end and by page 170 is a cowboy and a bounty hunter and a hero who goes on a romantic quest and saves his woman.

But beyond that, a lot of people have asked me today if there was a message I was trying to get across about slavery. I wasn't trying to get a particular message across so much as I was trying to paint a realistic picture of what America was like at that time and create a world where slavery is the norm, and to the people who are dealing with it - the slaves and the slave owners and the slave handlers - that that is how it's going to be for the next few hundred years, at least, if not a thousand years. This is just the way it is. And then create that version of America that existed then and just put you right in the middle of it so you have to deal with that America. That is what I was trying to do rather than make some soapbox speeches about slavery or make points against America, I just wanted to set up America at that time and just take you back to that time, one hundred percent, and stick you in the middle of it. That was the idea.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.