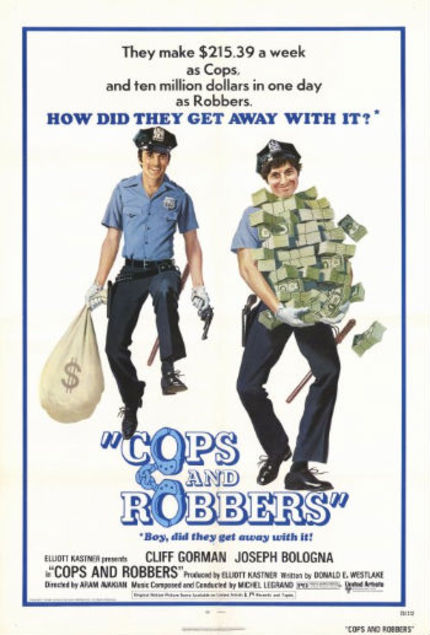

70s Rewind: COPS AND ROBBERS

His books began to be adapted into movies with Jean-Luc Godard's Made in U.S.A. in 1966, followed by The Busy Body, Point Blank, Pillaged, The Split, The Hot Rock, Cops and Robbers, The Outfit and Bank Shot, all within a period of 8 years. As a young reader, I was drawn to his novels because they were straightforward capers and read "fast," i.e. real page-turners; you didn't know what was going to happen next. As an adult, I remained a fan because I appreciated to a greater degree Westlake's craft in establishing mood and his ability to define characters with an economy of words that is often breathtaking in its simplicity.

In part, that's why Westlake's work translates so readily to the cinema. The plots are easy to follow, the people he invents are driven by their own distinctive personalities, the dialogue is sparse, often witty and always to the point. And you're never quite sure if foolhardy criminal behavior will ultimately be rewarded -- or undermined by incompetence and sheer chance.

All those qualities are on display in 1973's Cops and Robbers, a plot that, in the hands of another writer, would have been utterly routine. Westlake adapted his own 1972 novel of the same name, though the screen credit simply says, "Written by Donald E. Westlake." He adapted his own work one other time, with 1990's Why Me?, on which he shared credit. He occasionally adapted the work of others (Jim Thompson's The Grifters, Patricia Highsmith's Ripley Under Ground) and occasionally wrote directly for the screen (Hot Stuff, The Stepfather) and television (Fatal Confession: A Father Dowling Mystery).

Director Aram Avakian had made only a handful of films. His previous effort, End of the Road, an adaptation of a novel by John Barth that featured photography by Gordon Willis and was rated X. According to Roger Ebert, it depended more on "mood and implication" than plots, which makes one wonder why he was selected for Cops and Robbers, which needs a snappier pace to match the jazzy banter of the lead characters. Avakian films the proceedings in a rather static, routine manner that does little to add to the script. His style can best be summed up by Charles Grodin's description of Avakian's next film, 11 Harrowhouse, as "very, very slow." To his credit, Grodin, who was coming off his great success in The Heartbreak Kid, took responsibility for playing the lead role "in an extremely passive manner." He volunteered to write and voice a narration that played to a much more favorable response from test audiences, according to his book "It Would Be So Nice If You Weren't Here." (Published by William Morrow & Company, pages 212-214.) Whatever the case, Avakian never directed another feature film.

Getting back to the movie under consideration: Who else but Westlake would dream up a story in which two New York City police officers decide to steal $10 million by pretending to be criminals who are disguised as New York City police officers?

Tom (Cliff Gorman) and Joe (Joseph Bologna) are best friends and neighbors. They're also good, honest cops who resent the stench of corruption that's rubbed off on them by their colleagues who are on the take. But that doesn't stop Joe from calmly walking into a liquor store and robbing it in the opening scene. Nonplussed, he later explains to Tom: "Hey, I got four kids. Forty bucks is four pairs of shoes for my kids."

Tom is flabbergasted by his friend's actions, and maybe even more so by Joe's casual attitude about the whole thing. It has an effect on him; he starts looking at the daily dangers of his job, the casual lack of integrity among his fellow officers, his own limited income, in a new light. Gradually, he comes around to Tom's point of view.

Tom and Joe are definitely not stupid, but they've never planned a crime before, and their inexperience shows as they seek to set up a job through a well-connected, middle-level Mafia boss. The robbery they then concoct is clever but rife with the potential for going wrong at the worst possible moments. Which, of course, it does, to delightful effect.

Near the beginning of their film careers, Gorman and Bologna make a fine team with good chemistry. Tom and Joe are sweaty, grimy, gritty, and wisecracking, street guys who love their families and have tried to play it straight, but ultimately frustrated by a system that all too often rewards criminals and keeps the police far down in the pecking order of comfortable material prosperity.

Westlake's fingerprints are all over the movie; he's as much the auteur as anyone. Maybe if he'd been in full control of the project, or had a more fitting collaborator on the production side, it would have been better paced and someone other than the ill-matched Michel Legrand would have scored the film and composed a couple of inappropriate soft-rock songs to pollute the soundtrack.

Be that as it may, Cops and Robbers fits well into the early 70s aesthetic of atypical cop movies and deserves attention as a rewarding pleasure.

Credit: Thanks to Lawrence Block for inspiration.

Viewing Note: I saw the film in high definition via cable channel Turner Classic Movies. The source material displayed some speckles and dirt, but otherwise looked very clean and very good. Cops and Robbers is available from MGM on Region 1 DVD.