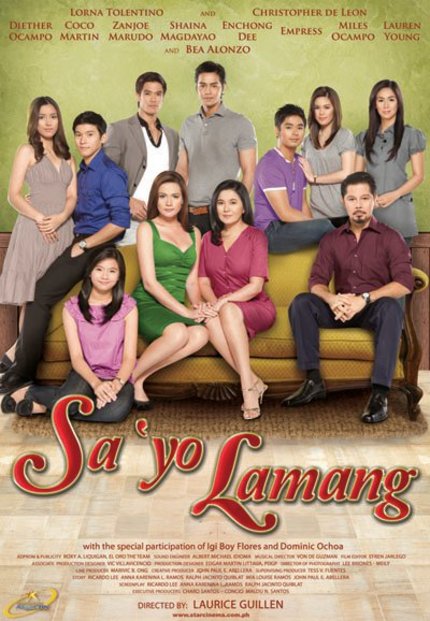

SA'YO LAMANG Review

The story of Laurice

Guillen's Sa'yo Lamang is hardly new.

An imperfect but seemingly stable family disintegrates into chaos as one by

one, the family members figure serious conflicts and secrets, whether from the

past or the present, conveniently unravel, threatening the sheen of normalcy

that has sustained the family through the years. From Jeffrey Jeturian's

low-budgeted but elegantly staged Sana

Pag-ibig Na (Enter Love, 1998),

to Wenn Deramas' lowbrow yet unpretentiously enjoyable Ang Tanging Ina (The Only

Mother, 2003), to Joel Lamangan's middling and intolerably weepy Filipinas (2003), to Brillante Mendoza's

highbrow and provocatively stirring Serbis

(Service, 2008), the Filipino

family has been exposed, crumbling in the midst of dire needs or expanding

generation gaps or the simple passage of time.

The family, considered as an

invaluable social element, is a persisting Filipino need. In the absence of it,

a typical Filipino, in his desire to find personal comfort by means of being

part of a social circle, would always seek a replacement. Thus, the idea of the

concept of family dissipating to irrelevance because of

very-real-to-the-point-of-being-cliché eventualities like infidelity, jealousy

or something as natural as death is a gold mine for cinema. The threat to the

family is a fear that is always relatable, no matter how fantastically

conceived. Translated to cinema, where there is always the protection of the

knowledge that whatever tragedy happens onscreen dissipates as soon as the

credits roll and the lights are turned on, the viewer is allowed to be emphatic

to aches of the cinematic family despite the differences between his familial

history to the fictional one depicted onscreen simply because he can relate.

Sa'yo Lamang,

like Guillen's Tanging Yaman (A Change of Heart, 2000), an

earnestly-made soap that explores long-repressed aches among siblings as they

claim their respective shares in the estate of their still-alive mother who is

slowly losing herself to Alzheimer's Disease, borrows its title from religious

songs whose words, if taken away from the backdrop of Catholicism, can also

play like a secular song about love. Sa'yo

Lamang, as opposed to Tanging Yaman which

is explicit in its religiosity in a way that God actually becomes an actual

participant in the narrative, wears its religiosity within the context of a household

of sinners. It's a tricky premise that Guillen interprets deftly and without

having to place judgments by sudden changes in moral perspectives and

personality. In the film, faith, a concept that is as human as the moral

dilemmas and sins that continue to turmoil the film's various characters,

instead of the saving power of the Catholic God, is the thematic center.

Because of this utility of something as universally appreciable as faith

instead of belief systems that are endemic to the Catholicism, the film's often

brushes with prayers and rituals are never obtrusive. Instead, they become rousing

centerpieces of the effectively contoured ensemble drama.

Guillen intelligently frames

her actors during the film's most sublime moments to emphasize their commendable

performances. When Coby (Coco Martin), frustrated that his pregnant

ex-girlfriend (Shaina Magdayao) has been allowed to stay in the family home,

rapes her and in the middle of the rape changes his hateful stares to looks of

pity, mercy, and perhaps, love, Guillen communicates the surprising change of

heart via an extremely tight close-up, allowing her actors, Martin with his

invaluably expressive eyes and Magdayao with her exquisite turn as a woman who

has suffered enough to accept anything as simple turns of fate, to take part in

the storytelling. In another scene, Dianne (Bea Alonzo), after being sobered by

her mother's wishes that she reconcile with her father (Christopher de Leon),

quietly yet achingly explains to her father why it is so difficult to do so.

The room is dimly lit, and Guillen smartly makes use of the limited light and

the persisting shadows to dictate the mood. From a close-up of Alonzo's stoic

face while uttering words that can only devastate her father, the camera zooms

out to reveal De

Lorna Tolentino, who gives

life to the character of Amanda, the mother who single-handedly raised her

children for ten years, consistently delivers a tremendously moving

performance. Starting out as a seemingly weak character as she is left in the

background by Dianne who dominates the household, she shapeshifts, and little

by little, exposing cracks to her character, some of which are reprehensible.

By film's end, without transforming inexplicably, she becomes the most human of

all the characters. Inasmuch as Guillen has poured her mastery of the

filmmaking craft and her personal convictions as a Catholic mother who has

suffered and survived familial hardships through faith to the making of the

film, she generously allows her film to also belong her actors who portray

their roles with a proficiency and sensitivity that is pleasantly surprising

even from the cast-members who've already established reputations as great

actors.

Midway through the film,

Guillen makes use of a flashback, awkward because of the sudden marked

difference in aesthetic but awesome in the sense that it is not only a

flashback for the character, but also to the film's viewers. Illuminated

differently with the faces of Tolentino and De Leon giving off a cool bluish aura

instead of the warm golds and yellows, scripted in a way that every shouted

word contains a powerful emotional charge, blocked in a way that recalls the

most typical of melodramas, the flashback allows a glimpse of an era where

dramas, despite their lack of affinity with how the real world works, always

had something to say, or if it didn't, were at least beautiful pictures that

earned every tear, every sob, and every peso they asked from their viewers. The

flashback felt like it was scene from Guillen's earlier films, films where female

characters were liberated from the bounds of a male-dominated society and took

control of their lives resulting to shouting and crying expeditions, films that

can be very good despite the commercial preconditions of their bankrolling

studios.

Sa'yo Lamang

gives me confidence that Star Cinema and these other mainstream studios will

start respecting the genres they mine for cash. It allows me to believe that capitalist

and artistic aspirations, although theoretically always at war, can also

co-exist as long as integrity, instead of profit motives are the primary

consideration. Star Cinema, there is hope for you yet.

(Cross-published in Lessons from the School of Inattention.)