Tribeca Film Festival: MOON Review

Co-writer/director Duncan Jones’ debut feature Moon (2009) is a modest but nonetheless exciting bit of derivative speculative fiction. As the film’s vision of the future is obviously cobbled together from a myriad sources, most importantly 2001: A Space Odyssey and Solaris, it only really becomes involving after the first half hour has given us sufficient set-up and even then it’s hardly the most original story. Jones and co-writer Nathan Parker add nothing to the mythic canon they’re working in but do provide a very satisfying bit of genre falderal, albeit one that’s a little too literal-minded.

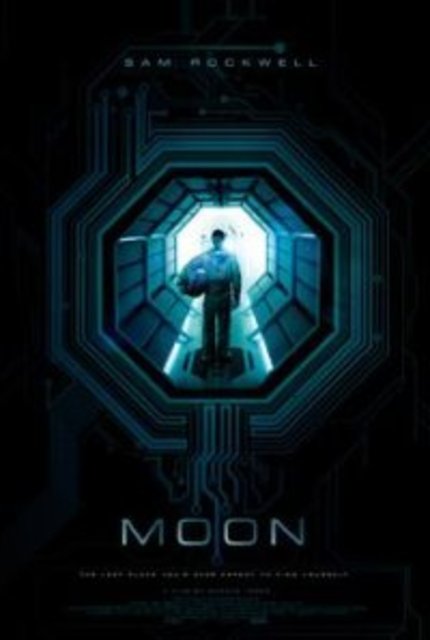

Moon trains in on the fears of loss of personal identity that both of the two major films I name-checked had but through the lens of a one drone against the world story, ala Silent Running. Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell) works alone in a space station on the far side of the moon mining He3, the alternative energy source that 70% of the world runs on. Without any means of direct communication with people back on Earth, Sam’s only human contact comes is supplied by his faithful robot assistant Gerty (Kevin Spacey) and video messages sent to and from his wife and bosses. After almost three years on the station, Sam’s got a bad case of cabin fever, making it only a matter of time before he starts seeing people that aren’t there; unfortunately for both him and us, they aren’t all in his head.

That kind of deceptive matter-of-factness is crucial to understanding why Jones’ film works as much as it does and why it also refuses to go farther in its speculation. Once Sam goes in search of the person he sees stranded in the middle of nowhere, the signs of his mental deterioration take a backseat to the physical toll he’s taking in his quest for answers. Scars and wounds matter a great deal in the film, but instead of being used as mirage-like signs of Sam’s mental state go, they’re used as just some of the “real,” observable clues that inform us that everything he’s questioning is in fact tangible. The blinking lights on the station that insist that certain functions are offline are not hallucinations and neither are the places and things Sam’s visitor’s conspiracy theory ravings implicate. Nothing is left up to Sam’s imagination, making all the clues we have to go on disappointingly objective.

Take Gerty for example (SPOILERS HERE). Unlike a HAL 9000, Gerty has facial features projected via a comic yellow smiley face that shifts with its mood. Gerty’s initially reticent to address Sam’s questions but about mid-way through the film, it starts to not only tell him bits and pieces of what he wants to know but it even eventually starts to help him. In fact, when Sam needs to delete Gerty’s hard-drive to make sure that the higher-ups at Lunar don’t catch wind of his actions, we cry for the selfless toaster because he’s making the ultimate sacrifice to prove that he is in fact on Sam’s side.

I might be able to believe that the computer Sam’s spent so much time with is human after all, but if you removed the moral certainty that that humanity provides, the kind of loneliness that permeates the film would be far more affecting and memorable. Gerty’s just a mechanical construct and the fact that we can see that his actions are really all in Sam’s interest is immediately satisfying but ultimately dispiriting. In the same way, the fact we can see “the secret room” and can observe that the mysterious spire that’s all the way out there is in fact blocking simultaneous video broadcasts means that the world Sam’s living in is in fact grounded in reality. That’s all well and good but when the foundation that that ground is built on is recycled as it is here, something’s amiss, even if everything else in the film feels so damn right.