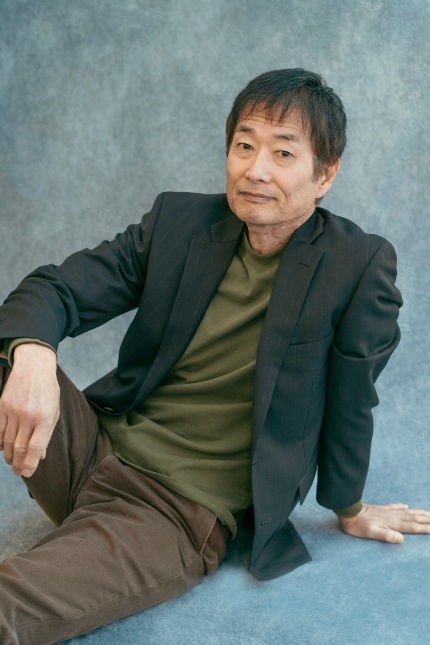

Berlinale 2025 Interview: THE LONGING Director Toshizo Fujiwara Talks Social Realism, Mentorship, and Learning From Each Other

Toshizo Fujiwara is leaning forward in his Zoom window as I speak, listening intently and smiling in recognition. We’re discussing the warmth that he demonstrates towards people in his filmmaking, and the more that he shares, the more the rhythms of his cinema make perfect sense.

Fujiwara has worked in past decades as a theatre director and as an actor. In the film world, he’s spent much of his career on the sidelines, playing a small part in narratives driven by people and their interpersonal bonds, and observing their directors and how they motivate actors to deliver those stories. This history informs The Longing (Mikusu Modan), Fujiwara’s third feature as director, which celebrated its World Premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival this month.

Society at large would easily abandon young offender Yuto (Daiki Ito), but 53-year-old Okonomiyaki restaurant owner Hiro (Fujiwara) has other ideas. Upon Yuto’s release from prison, he’s put to work in the restaurant, strengthening his ties and his work ethic as he readjusts to the everyday. But Yuto is searching for something. His mother abandoned him as a child, and his father has since left town. He soon finds the connection he craves in Yukiha, a young dancer that he meets at a nightclub. But Yukiha is a kindred spirit in more ways than one.

Filmed in the real-life locations that inspired it, The Longing is a film that’s enriched greatly by delving into its contexts. Propelled by our love of unsung people, the interview leaves us both smiling.

I'm curious as to what sparked your interest in filmmaking, as you were in front of the camera in the decades prior.

When I was a student, I made experimental films and had a dream of becoming a film director. When I was in my mid-20s, there was an audition for a smaller part in Kurosawa’s film Kagemusha. Naturally, I was very interested. I joined that production for a month and a half, and it sparked my interest in filmmaking yet further.

You've appeared in films by Akira Kurosawa, Takeshi Kitano, Shunji Iwai, and Hal Hartley. It’s a broad spectrum of directors. Has your work with any of these filmmakers influenced your own style?

Yes, I think they really have, especially Kitano. I joined his production [A Scene at the Sea] as one of the central characters, so I had a rich experience working with him. I learned that we don’t have to force actors to play their roles. You should instead respect the uniqueness of their personality and character, rather than pushing them to act a certain way. Kitano always told me that.

Your first film was adapted from your own play. Does stage theatre influence your approach to filmmaking? There's something in the way that you give a very rich inner world to your characters.

I have over twenty years of theatre experience, and that shaped my approach to advising my actors. Rather than writing a complete script and giving it to them, I prefer to create the script together in rehearsal — to keep it collaborative, rather than concrete. Most of the cast in this film were selected through auditions, and we worked together to craft characters that matched their own personalities.

Tell me about your young actors. It's beautiful symmetry, because you're mentoring these characters off-screen as director and also on-screen as their guardian figure.

I spent a lot of time searching for an actor that matched what I had in mind for the protagonist, and I’m glad that we found him. When developing the character, rather than saying to the actor that the character has to be such-and-such, we spent a lot of time probing “how would you do it”, and “if you were the character, how would you react in this given situation?”. We kept that conversation going throughout the process.

As an actor myself, with more experience, I meet him at his level rather than asking him to reach up to me. I try to see his perspective. The relationship between myself as a director and him as an actor was indeed quite similar to our two characters in the film.

It’s a really lovely collaborative process, and it imbues the film with a living, breathing feel. I found myself reminded of the English filmmaker Ken Loach. Is he an influence on your work?

Ken Loach is one of the directors that I respect the most. His films greatly inspired my directorial style. I once saw a behind-the-scenes featurette about one of his works. He too spends a lot of time rehearsing with actors before shooting. Seeing that told me that my approach to directing actors isn’t wrong. That was the moment that I became more confident in my directorial style.

What draws you to exploring social issues in your films, personally speaking? There's a real warmth that you feel for your characters evident in the film. You want to give these characters a chance.

When I was a teenager, I wasn’t a ‘good boy’, per se. I see myself in this film’s protagonist. I made a lot of mistakes when I was young. If I start explaining each, it would take too long. But every time, there was an adult who would support or rescue me from those situations.

Ten years ago, I saw a TV programme about the president of an Okonomiyaki restaurant that employs people who have recently completed their prison sentences, helping them to reenter society by giving them a job. That was the model for this film’s premise. I was deeply impressed by his activities, and I wanted to make a film related to that topic.

Tell me about your cinematographer, Mamoru Gomi. A lot of the framing here is quite unusual and inventive.

This is our second time working together, the first being my previous feature, The Sky and Beyond. We leaned towards a documentary style for this film in the lighting and camera movement.

What did you shoot this film with? This film has a really nice, slightly grainy, textured look to it.

The original footage was shot with a Blackmagic camera in 6K. But, in the editing suite, we added a film damage filter, as we wanted to evoke the texture of older cinema.

What do you hope that this film brings to the lives of the people that watch it?

I hope this film shows people that they should never disregard the smallest possibilities available to them. If you keep searching, you will see light within this darkness.

The Longing had its World Premiere at the 75th Berlin International Film Festival. With thanks to Kanako Fujita for interpreting and to Amane Oshima for facilitating.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.