INSHALLAH A BOY Review: A Situation To Crack Under

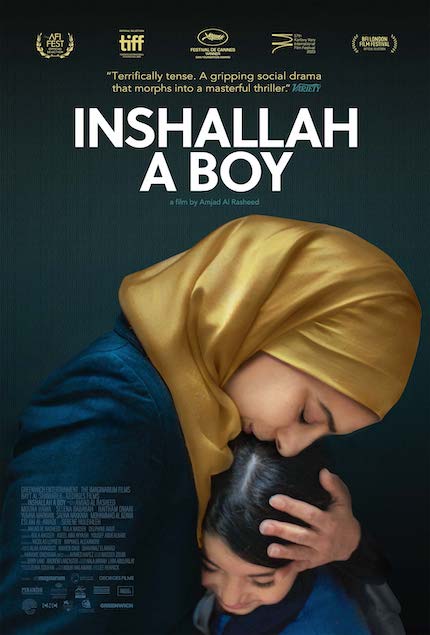

Last year, the Cannes Film Festival crowds screened its first ever Jordanian film, and simultaneously, the debut of director Amjad Al Rasheed. Inshallah A Boy is about the hypocrisy of vultures in times of grief, the societal constraints of a widow in a tight spot, and the resulting defiant struggle.

In modern-day Jordan, Nawal (Mouna Hawa) wakes up to a dead husband. The sympathetic sentiments of those around her come with conditions, mainly, her late husband's brother insisting on an unsettled debt and claiming half the inheritance. It is his lawful right, as Nawal only has one young daughter and no male heirs.

Half of the house is Rifqi's (Haitham Alomari). Nawal pushes back against the ridiculousness and injustice of dividing a house; it would have to be sold, leaving Nawal and her daughter homeless, or Rifqi would switch houses with her. The threat of Nora's (Seleena Rababah) custody hangs in the air.

Grief is turned into an opportunity to exploit those the laws unfavours. To buy time, Nawal states that she is pregnant. The possibility of another heir delays the inheritance being settled, but she must now prove her pregnancy.

It is important to note that Inshallah A Boy is not about the mechanisms of sustaining a lie as much as the emotional toll of it, the choices to be made and prices one must pay when every morning brings in a new problem and staying afloat is the only priority. Nawal is forced to compromise principles like honesty, fidelity to her late husband, and even her stance on abortion. The ensuing moral dilemma leads to an unforgettable conversation about what real sins might be.

This is not a story about surrender to sin. A husband's death can't be fought -- other things can. Nawal begins to confront figures like her boss and her brother-in-law, eventually even saying to him: "I am not your sister." Rarely does a fictional character inspire so much respect.

Mouna Hawa's performance is both incredible and grounded in the human. The director stresses the importance of body language and how he spent several years on the casting process. It shows.

The film's concern with the political's influence on the domestic is well-shown in the contained rooms that most of the action happens in. Even the judge's office is a claustrophobic little room. On the rare instance where we see an open landscape, Nawal has escaped with a coworker who is in love with her, who teaches her how to drive and might lend her money. Seeing the open sky is a change of pace for the audience, and drives home how suffocated Nawal is by her circumstances.

The domestic is crucial and interwoven. Nawal might lose her home and her daughter. There is a mouse in the kitchen no one can get rid of. A neighbour takes care of Nora while Nawal is at work.

Nawal's workplace is an upscale home, taking care of an older woman, where she regularly interacts with said patient's daughter and granddaughter, Lauren (Yumna Marwan). There is kindness and there is throwing each other to the wolves. The point is that Inshallah A Boy does not take a didactic or unitone stance about female relationships or domestic spaces, instead showing their range and complexity as they interact.

Take the well-off Lauren, sometimes a comrade and sometimes rude to her employee Nawal, always with her hair on display, who says: "We are in the same shit." She does this as she slips Nawal some bills after an intimate moment of caring for one another. It's true that Nawal needs the cash, and it's also true that the moment of tenderness is spoiled by re-affirming the employer's position of capital power.

There is a strong undercurrent of the idea of a "superwoman". It's what the granddaughter is accused of, for her views on marriage and sex. It's what we see Nawal taking on scene after scene, complication after complication. It's what no one can do to match the deus-ex-machina ending. Without saying too much, there is an element of the divine and its protection.

When asked about the anticipated audience reaction at a Q&A conducted for Awards Radar, Amjad Al Rasheed responded: "It will help open a conversation." That much is certainly true.

The film is now playing at Film Forum in New York and Mountain Shadow Film Society in Walnut Creek, California, via Greenwich Entertainment, and will expand to other theatesr in the weeks ahead. Visit the official site for more information.