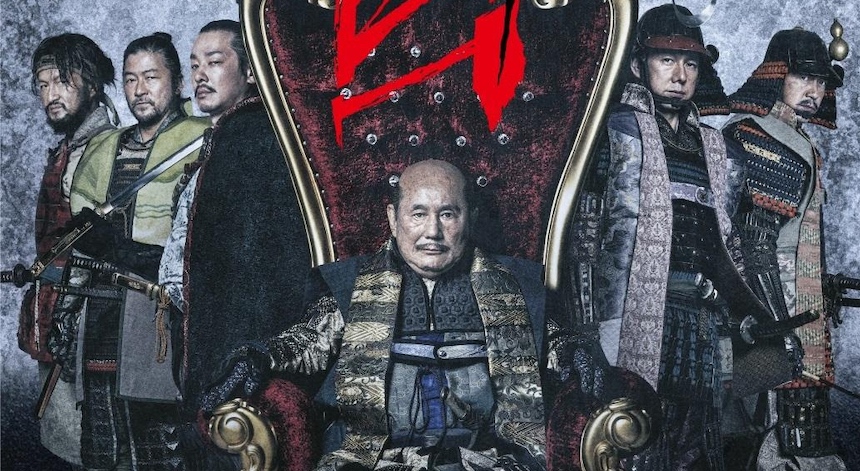

Cannes 2023 Review: KUBI, Masterclass in Absurdist History

Takeshi Kitano's new film.

"From the day you're born, life is one sick joke".

One can imagine many a character in the Takeshi Kitano canon breathing these words or at least feeling this way, but perhaps nowhere are they better suited than in his latest symphony of surreal violence; a rare foray into Japanese history for the now 76-year-old writer/director/actor, who tends to set his absurdist bloodbaths in modern day, aside, of course, from his deep-red splatter take on the blind swordsman, Zatoichi, twenty years ago.

But in Kubi, Takeshi Kitano/Beat Takeshi, the auteur/star with the facial tick of gold, goes full-on epic in his tale of warlords battling it out to become ruler of the Sengoku period. At the film's outset, the power belongs to sadistic warlord, Oda Nobunaga, the forceful unifier of Japan, who after an insurgency from a former disciple-turned-fugitive, Murashige, is feeling exposed, distrusting, and more than a little bloodthirsty.

Ill at ease with the competency of his own kin, Nobunaga tells his vassals that the throne is for the taking by any one of his hardest-working subjects, but the seeming contenders are Mitsuhide, played by Drive My Car's Hidetoshi Nishijima, and Hideyoshi, played hysterically by Beat.

As interested as the film is in its sprawling, oft-told history, far more so, Kitano uses his black sense of unearthly humor, having fun with Japanese period drama in a way seldom seen in these types of epics. One such ongoing bit that never fails to elicit laughs is the fun he takes in perhaps referencing Kurusawa’s Kagemusha (The Shadow Warrior), in which double after double is mercilessly slain only to be immediately replaced by an unending well of would-be daimyō doppelgängers.

Cohabitating the wartorn lands are a host of memorable ensemble players, like a misguided peasant hellbent on becoming a warrior of honor through disgraceful means, a satirically homely geisha madam, and a former ninja, who presently functions as a wandering comedian. But Kitano is at his best when portraying the deranged whims of the excessively powerful, often motivated above all else by boredom rather than conquest, and with his dreamlike presentation of meaningless violence in an existentially frightening landscape.

One highlight of the film occurs during a visit to a surreal woodland festival in which a village ritualistically prays for death without haste. ‘What kind of insane village is this?’, asks a visitor. ‘What kind of insane world is this?’, comes the response.

In a world where power is gained through decapitation and the subsequent collecting of heads, Kitano is having a ball reveling in the random mercilessness of history and the absurdity of royal dominion. Those trained to experience historical epics come to a more typical head may perhaps be confused by the anti-climactic culmination of Kubi, but fans more accustomed to Kitano’s sideways aesthetics ought to find plenty to love within. It’s a highly original and ticklingly amusing take on a genre done to death and that alone is enough for the film to warrant a deserving cult status.

In remembering the many peaks of Kubi, of which I found no shortage, my mind again goes to the ninja raconteur who after every performance asks his audience to throw money his way if they laughed. If Kitano were in front of me, I’d throw him much yen.