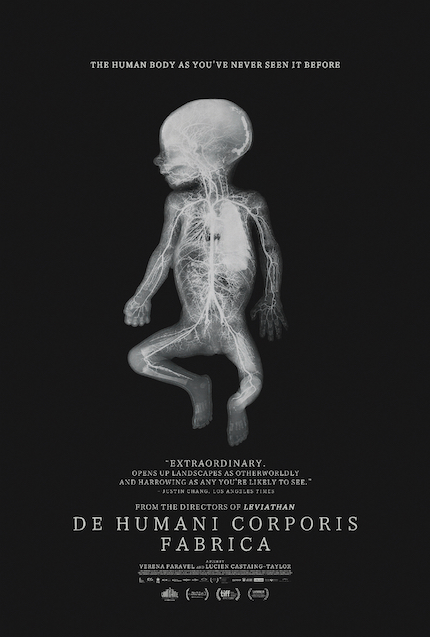

DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA Review: Landscape of Flesh

Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor ('Leviathan') directed the documentary.

Hospitals are places of miracles and horrors. They are also places of office politics, temporary domestic spaces, and a kind of body-repair shop.

The reason why there are so many television medical dramas is that everything about these places is physically and emotionally (dramatically) heightened. Life and death and all that, sure, but also the waiting, the processing, and god willing, the healing.

Anthropological documentarians Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor offer a grimy and profound (or is it profane?) look into the orifices and arteries — the anatomy — of the modern hospital and the human body. De Humani Corporis Fabrica is not an easy watch; you hear the hospital staff at work, and you see their patient’s bodies under repair. Modern high-resolution cameras can penetrate everything from the human eye to penile urethra. Here we are space-voyagers, or perhaps interlopers, into the human body, and it is a strange, squishy place.

Our guides through this strange land are the filmmakers, who are not without a sense of humour, or a sense of compassion, but theirs is a stoic eye as well. Over the course of several major surgeries, from spinal repair to Caesarian section, the camera does not reveal what is happening for some time; it allows us to dwell in the mysteries of the human parts before ‘pulling out’ as it were (literally, figuratively) to reveal. There is a curious humour in the cinematic language here, which makes the film all the more compelling.

David Cronenberg’s Crash used Toronto highways as a visual metaphor for blood vessels and pumping arteries, De Humani Corporis Fabrica juxtaposes the corridors and hallways with human innards. At one point, the similar cameras that are used to see the inside of the small intestine, are attached to the large disposal container for assayed bio-waste, allowing us to zip along the pneumatic disposal system, as if we were watching the final chapter of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

But it is not all experimental abstraction. We see stressed doctors drop instruments, mid-surgery and have to figure out solutions on the fly. Mistakes are made. We see the elderly wards of various Parisian hospitals, one of the wealthiest world-class cities, it is worth noting, where dementia and acute lack of purpose are nearly impossible issues. We see modern institutional inefficiencies and lack of resources, where compassion falls through the cracks.

A rhythmic primal scream will linger and haunt. Nurses and doctors are overworked, patients are overlooked, this is the sort of thing that COVID-19 shoved back in society's face. In a way, De Humani Corporis Fabrica is difficult, essential viewing. Perhaps more than the esoteric (if excellent, and also difficult) fly on the wall obscurities of the filmmakers' previous fishing voyage (Leviathan) and cannibal inquiry (Caniba).

De Humani Corporis Fabrica open and closes with graffiti: Vagrant’s scrawlings on the basement walls, that the security guards walk by barely noticing, and the orgiastic mural the camera lovingly lingers over during a retirement party for one of the surgeons. (To the needle drop of the extended mix of New Order’s Blue Monday.) In these latter moments, it is a very human release to the trauma of the our existence and our maintenance, and those who toil to keep the machine running.

First published during the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2022. The film opens Friday, April 14, in New York at IFC Center via Grasshopper Film. Visit the official site for more information.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.