Montreal Nouveau 2021 Review: ZERIA, A Fractured Story of a Dying World

What are the stories that will be left for humanity, if (or really, when) there is a shift in how we live? Or where we are? What are the ideas, histories, feelings, we need to impart to the next generations, and what would be the purpose of these stories? Do we talk of the grand and epic, or do we tell the smaller stories, of joy and pain, of our lives? What shall we impart for the next world?

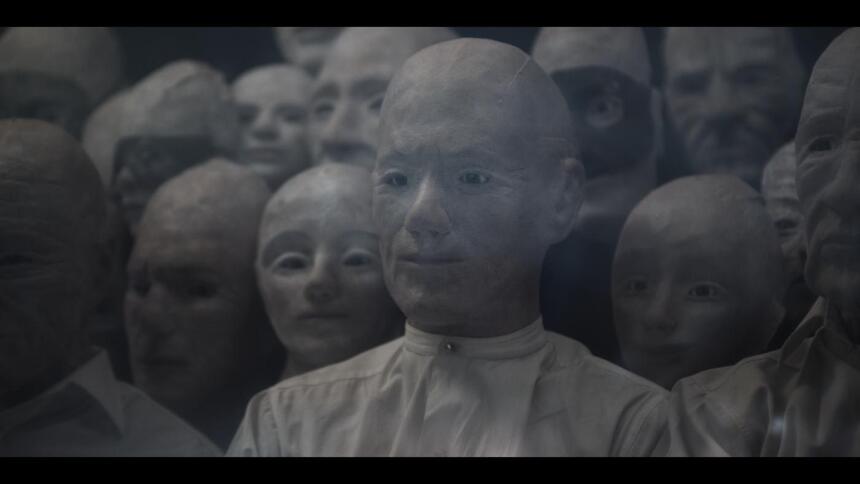

Belgian actor and director Harry Cleven takes a rather experimental and disquieting course of storytelling at a particularly end, or transformation, of humanity and the world, in Zeria. Obstensibly a stop-motion animation film, it combines some puppetry and models along with humans in puppet-like masks to tell its stories of the last days of humans on earth, as a shift in existence means a way of life is lost, perhaps for bad, perhaps for good.

In the not-so-distant future, it seems humanity has finally worn out the planet Earth, and the great migration to Mars is almost complete. Gaspard, an elderly man and one of the last humans left, is composing a letter to his grandson, who will be one of the first humans born on the distant red planet. Gaspard will never meet him, and his grandson will never know Earth, so Gaspard tells his lfie story; but it's not just his life, it's also the life of the planet, as humans have known it, loved it, and abused it.

The film begins with voice over narration (indeed, the only voice we will really hear during the film, which adds to its dislocation and disorientation), as Gaspard introduces himself to his absent kin. A camera slowly glides over a model of a city, overgrown with weeds; an image many will have seen from other dystopian tales, but which keeps us at a distance. So, too, the use of puppets: sometimes full puppets, but frequently people which puppet heads, their movements more like that of a strange dance.

This fragmentation: the voice over, the puppets, the models, sets us in a kind of theatre, in the round perhaps, as we become both the observers from Mars and the last humans judging this story and its telling. And the story that Gaspard tells is one of darkness: a journey of sexual abuse, of longing for the love of a parent, in a world that is disintegrating, both in form and function, mirrored in (and mimiced by) the humans that inhabit it. These strange masks, these strange bodies, set against Caligari-like sets, images that come through distorted, remembered by an aging mind, feel as a strange anthology of a single life.

Indeed, this is a story told by a fractured mind, to a person who would not recognize a story that was told more directly, since there is no context for those who are no longer of the earth. This contextualization of a life that is haunted by trauma and the search for meaning, makes more sense if the identities are disguised; or perhaps, these puppets, these bodies moving in gestures of interpretation, are more accurate to the human experience than any news report or home video that is the usual expected archive.

Like a video art installation that seems destined for a corner of the museum of humanity, Zenia feeds on the strangeness of existence at the seeming end of time, a small report of the apocalypse from an intimate and uncomfortable history, one which grasps for connection as the old world fades away.