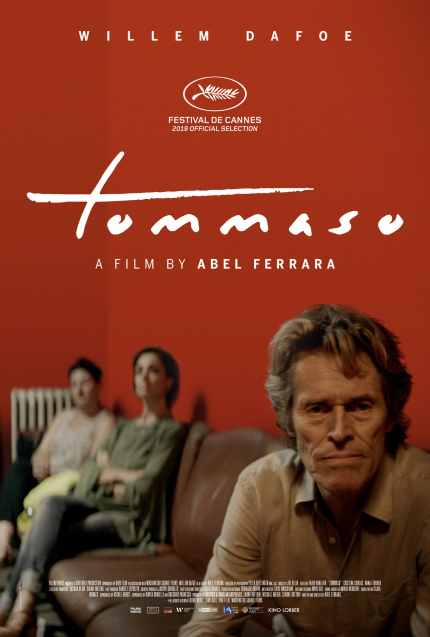

Review: TOMMASO Stars a Riveting Willem Dafoe As Abel Ferrara Stand-In

The unexamined life is not worth living.

The half-examined life isn’t worth living either or - to be more accurate - isn’t worth documenting in narrative film, let alone a character study with a two-hour running time and a loose, unfocused structure that suggests a filmmaker, Abel Ferrera (Body Snatchers, Bad Lieutenant, The Funeral, The Addiction, King of New York) wrestling to find meaning in or meaningfully engage with half-formed, underdeveloped ideas in a lightly fictionalized meta-drama about a filmmaker at a personal, figurative, ultimately spiritual crossroads.

That Ferrara’s latest film, Tommaso, succeeds as a tour-de-force for Willem Dafoe, an oft-underused, underutilized performer, while failing as a character study or meta-drama, comes less as surprise or disappointment then as the not an entirely unwelcome price moviegoers have to pay to see Ferrera still taking risks decades after debuting in 1979 with The Driller Killer, a controversial grindhouse entry at the time that eventually became a cult classic.

Working from a limited, modest budget, Ferrera used his own apartment in Rome where’s he lived for the better part of two decades, cast his wife, Cristina Chiriac, as Nikki, the fictional wife of Ferrara’s onscreen stand-in and title character, Tommaso (Dafoe), and Ferrara’s young daughter with Chiriac, Anna, as Tommaso and Nikki’s daughter, DeeDee. Ferrara introduces the audience to Tommaso’s daily rituals, from waking up, greeting his family, stopping by at a local cafe, learning Italian, teaching an esoteric acting class, and working on a slowly developing, barely glimpsed or heard screenplay for his latest film.

Apparently like Ferrara, Tommaso’s first marriage ended in failure, the casualty of Tommaso’s freewheeling, hedonistic lifestyle that left little for his wife or two daughters. Now drug- and alcohol-free, Tommaso practices Yoga and attends the local Alcoholics Anonymous as needed (i.e., often).

Tommaso’s hard-earned sobriety and stability take an almost devastating blow when he spots his wife (30 years his junior) embracing another man in a public park. It sets Tommaso on a predictable, if slow-motion, downward spiral. Rather, however, than challenging Nikki on what he saw or what he thought he saw in the park, Tommaso opts for an ultimately self-destructive passive-aggressive approach, shifting from conciliatory or confrontational, often within the same interaction with Nikki.

Ferrara creates a set of dialectical oppositions in Tommaso and Nikki’s floundering relationship, from the 30-year difference in their ages, their cultural differences (partly based on age, partly based on their countries of origin, the United States for Tommaso, Moldavia for Nikki), and language (they communicate mostly in English, sometimes in Italian).

Ferrara repeatedly pits Tommaso’s personal anxieties, insecurities, and fears against him, leaving Tommaso in an increasingly, unstable destabilizing position: Even as he fantasizes about the women in encounters in cafes and class, his fear of losing Nikki to another man (a virtual attack on his egocentric masculinity, self-esteem, and self-worth) crystallize into daydreams - or rather the equivalent of sunlight nightmares - that threaten to shatter the boundary between the objective world and Tommaso’s subjective reality.

As Tommaso’s tenuous grasp on reality continues to erode, Ferrara’s film follows suit, adding multiple layers of ambiguity deliberately meant to leave members of the audience in a virtual state of suspended animation. As Ferrara drops in references to a messiah-like figure, a nod to one of Dafoe’s best-known roles as the title character in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ three decades ago and Tommaso’s overinflated view of himself as a martyr to filmmaking art, they’re also meant as a self-critique of Ferrara and his self-image, albeit not a particularly profound self-critique.

Not surprisingly, Dafoe, working from Ferrara’s often schematic, underdeveloped script, adds just enough gravitas and depth to save Tommaso from devolving into self-parody and caricature. He adds shade, nuance, and color to a self-indulgent, borderline unrelatable character, delivering one of the better, more memorable performances in a career that’s spanned more than four decades.

With Dafoe and Tommaso front-and-center, however, that leaves little room for anyone else, including Cristina Chiriac’s near-inscrutable Nikki. At least until the final moments in Ferrara’s film, she’s more object - and object of male desire (and the male gaze)- than a fully rounded character with self-determination or agency of her own.

The film opens on Friday, June 5, 2020, in U.S. virtual cinemas via Kino Marquee.