Blu-ray Review: MATEWAN Sticks Up For The Little Guy

John Sayles’ retelling of the Matewan Massacre is a vivid look at the perils, and necessity, of organizing.

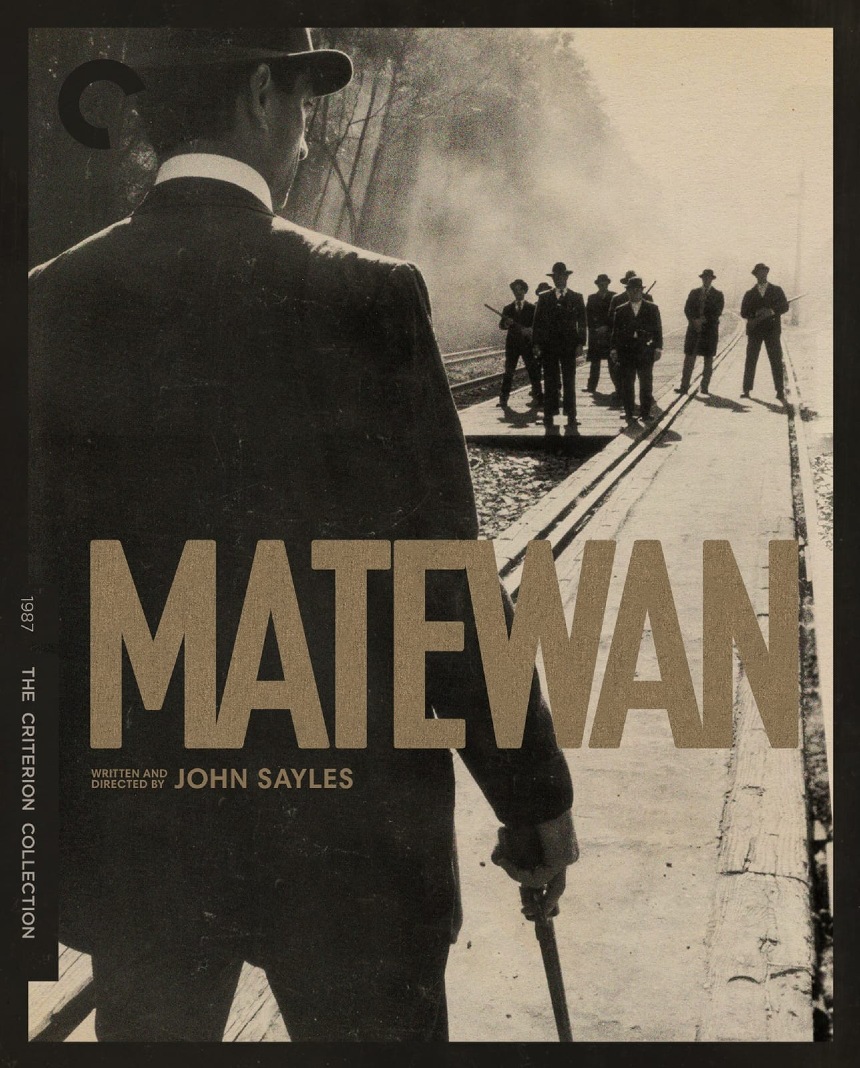

The Criterion Collection rounds the corner on its final three-digit spine number (#999) this week with John Sayles' 1987 union drama, Matewan, before busting our collective eyeballs (and wallets) with spine #1000 -- the Godzilla boxed set -- which hits the street on the same day. Don't let the latter overshadow the former. If the havoc wreaked by irradiated kaiju is oftentimes slyly political, Sayles' take on the Matewan Massacre of 1920 is brazenly so. It's as disturbingly fresh -- and arguably, even more relevant -- as it was when it was released. I wonder if they'll sell it on Amazon.

Taking place entirely in a holler in West Virginia where local miners are attempting to stand up to the mining company that is crushing them under its boot while simultaneously importing outside labour to render them irrelevant, Matewan sees the men band together to try to form a union. With machine-gun emplacements guarding the mine and more than a few Appalachian natives wandering the hills armed to the teeth, all-out war seems like a matter of time.

Into the fray wanders Chris Cooper's union organizer, Joe Kenehan, a soft-spoken pacifist and socialist who works to defuse the natural prejudices between the miner factions which, ultimately, only serve to strengthen the hand of the enemy. The enemy, in this case, is repped in town by a scouting party of two hired mercenaries who precede and foreshadow a much larger, armed force.

The film's central question -- can the workers come together in unified purpose by putting aside petty differences and justifiable anger in the service of something intrinsically unselfish and communal -- rings appallingly true to today's late-capitalist hellscape. Little more than a historical parable, Matewan is nonetheless so clairvoyant that critic A.S. Hamrah's topical essay in the Criterion Blu-ray's jacket directly references Donald Trump, who is merely the latest in a long line of bloated rich men exploiting the idealism of West Virginia coal for selfish, destructive ends.

The superb casting (by Barbara Shapiro) is one of the major draws for the picture. In addition to Cooper's first screen role and a powerful supporting turn by James Earl Jones, the key characters are filled out by masterful actors: Bob Gunton, Ken Jenkins, Kevin Tighe (as the corporate thug so vile you can sympathize with any miner who wants to bury a pickaxe in his head), Nancy Mette, Gordon Clapp, and Mary McDonnell. David Strathairn delivers what is unquestionably the most laconic lawman in the long, cinematic tradition of laconic lawmen. Will Oldham, barely 17 years old, becomes the heart of the picture as McDonnell's son, who becomes quietly radicalized by the growing conflict, and must ultimately choose between retributive violence, and an eye to something more lasting.

Photographed by Haskell Wexler, Matewan could arguably be the best-looking American film since McCabe & Mrs. Miller, sixteen years before, and yet another testament to the fact that for all the things digital can do extremely well, it can't gain something as simple as the gauzy gradations of the town mayor sitting in a bar in the late afternoon, or the rich pastel colours that play over the African-American miners' faces as they are shown their living quarters.

Sayles has overseen a 4K restoration of the film here, based on an archive print supervised by the late Wexler himself. The results are extraordinary. Early sequences are filmed with only the carbide lanterns on the miners' helmets as key light sources, but it is the world of Matewan that is the most striking to me on this rewatch. Rich, damp greens overflow in the frame as the Virginian hills cascade vertically through the frames behind the characters; the forest camp that the miners erect pops with detail, drawing attention to Nora Chavooshian's production design and Cynthia Flint's lovely costumes. Shot independently and written and directed by Sayles, Matewan in this presentation feels appropriately hand-crafted, the diligent work of a handful of key creatives uniting under a shared intent -- which, of course, underlines the story's themes, as well.

Chavooshian is featured in one of the disc supplements, in a 15-minute conversation about how she approached designing a film about an era (and a region) with which she had little familiarity. The film's production is further explored in two new short documentaries, Union Dues and Sacred Words, which bring out Sayles and producer Maggie Renzi, along with much of the principal cast, to recall making the film.

Inevitably, the conversation turns political, as none present are coy about the values their interest in the Matewan Massacre ultimately reinforced. This throughline carries to another featurette on the disc, Them That Work, which looks at how the production and release of Matewan ultimately impacted the West Virginia communities portrayed in the film. There's a tension between approved history (usually written and/or suppressed by the corporations) and the local heritage of work and exploitation that Matewan cracked open. It's important that the disc faithfully remind us of this fact: that for any licenses taken, the Matewan story is real, and in the 99 years since, very little has changed.

The film is available on Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.