Threading back to the summer of 1998, I catch glimpses of my 14-year old self, helping to build the very walls of the school he would be attending in but a few months time; this past I, a skinny American kid with the desire to know and be informed and explore, turned towards the realms of international cinema.

Akira Kurosawa’s Ran, a recommendation from my aunt, was the gateway.

My first encounter with Kurosawa on those war-ravaged plains of Feudal Japan lead to twenty years of an intensely strategic fascination with a long scroll of in-canon minted moviemen like Bergman, Kieslowski, Miyazaki, Teshigahara, Tarkovsky... or other, less frequently cited names like Angela Schanelec, Vera Chytilová, and Bill Forsyth.

Twenty years into my true cinephilia, there remains major gaps back on the silver screen shores of America.

This “lack” may have come about due to my rather adverse reaction to the rather static and stiff Hays Code era. When I began to encounter such films in my adolescence, I was more than happy to give my time and eye towards other cinematic shores. Heh. Chalk it up to black and white thinking.

Despite falling for the likes of Hitchcock and some of New Hollywood, as well as certain indie offshoots like Richard Linklater, my teen snob mind felt pretty confident in the assertion that American cinema wasn’t always the most sophisticated. Looking back, I now realize this all may have something to do with my adolescent self actually reprimanding my childself for watching Ernest and Jim Carrey movies. Teen angst can often mean hating or doubting the time you lived through.

Earlier this summer, I attended a double feature of Milos Forman’s Hair and Taking Off at the American Cinematheque’s Aero Theater.

The rarer film of the pair, Taking Off stars Buck Henry as a father stumbling after his “wild child” daughter played by Linnea Heacock. It is Forman’s first feature film foray after arriving in America from the then called Czechoslovakia. Presented as as a witty reverie of American paranoia and identity in flux post ’68, the film is a moderate production, somewhat akin to a chamber drama. Like Forman’s earlier Czech films, this initial step into American society demonstrates how much the filmmaker finds great rapture with the human face in all its variety, desperation, retaliation and spunk.

Here are two major guideposts for viewers to mark down while considering the film:

The first is a marvelous sequence that follows young female folk singers auditioning for an unspecified gig in a band or perhaps a musical, or talent scout auditions. The exact specifics don’t seem to matter to Forman. He is interested in the people. Their drive and their vulnerability.

Every kind of young woman, coming to sing, to play the guitar, without a man. It does not matter how well they play or sing. These people are seen as themselves.

Later on in the film -- after their daughter has disappeared again into the night -- Buck Henry and wife Lynne Carlin are at a fancy dinner for the parents of delinquent children. It is here that a doctor, and his “patient” played by the one and only Vincent Schiavelli, passes out joints to every single bewildered, be-speckled and bejeweled housewife, dentist, accountant, middle manger, and civics professor in the dining hall. Pairing these suburban husbands and wives, stunned into curiosity by the joint experiment, with the faces of the musical youth in the previous sequences, is the pinnacle of a very sharply drawn film. Considering these two pillars images, it is now about taking stock of just how silly and beautiful and sad this all is. For that’s what the movies do darn well.

In short, I find the film to be a compact masterpiece; a film that keeps things simple in story, plot and place, so as to allow for inner and outer states to merge.

It’s what Forman is all about, and it baffles me why Taking Off doesn’t stand side by side in conversation with some of his later films. Also worth noting is that the film features cameos from Tina Turner, one Kathy “Bobo” Bates, and an early days Carly Simon.

Of course this entry in the CineMage dialog isn’t really about reviewing lost gems or anomalies of 70s American cinema. If you want that, look to our own Peter Martin's 70s Rewind.

What this gets into now is less about film reviewing and more about patterns in film watching.

Looking over these summer months, there are three major patterns in my film watching.

First, the quick aside that I’ve been watching a lot of Ken Russell again, which is a very good thing.

The second, our major part for today, is that I’ve been watching and rewatching American films of various kinds, qualities, movements large and small, from the time my parents were teens (1970-74) to their time in the mid to late 80s when they had children.

These viewings included Hal Ashby’s vivaciously realist

The Landlord.

Susan Seidelman’s increasingly subversive and whimsical Desperately Seeking Susan. Penelope Spheeris’ heavy hitting

Suburbia. Alan Rudolph’s romantic laments

Choose Me and

Remember My Name. Then there was a rewatch of

Escape from New York: John Carpenter’s dark night of the soul.

George A. Romero’s dollhouse deconstructionist drama, Season of the Witch. Peter Weir’s humanist thriller

Witness. Bette Gordon’s working girl noir Variety

(pictured). The list goes on...

Mystic Pizza.

Heathers.

Maximum Overdrive.

American Gigolo.

Many of the above works cited are bounded by a deeply shared wound of American despondence, apathy, and exhaustion. A body culture and politik seeking lust and transformation, but often finding disease.

With, retrospectives, restorations and streaming, the films from this group directed by women have been gaining proper attention this past decade by cine-literate millennials and the back edge of GenXers, curious as to the world that existed in the years building up to their birth. My generation is like any other. They are hungry for some notion of "life before" and what that does and doesn’t say about them. For cinephiles in such a state of inquiry, that cinematic trace of the world of their parents before they were parents... the world of your grandparents before they were grandparents, is a silver screen sieve to the honest heartache and trauma that the country was facing before Reagan’s Morning in America beckoned the age of cocaine and cable.

With, retrospectives, restorations and streaming, the films from this group directed by women have been gaining proper attention this past decade by cine-literate millennials and the back edge of GenXers, curious as to the world that existed in the years building up to their birth. My generation is like any other. They are hungry for some notion of "life before" and what that does and doesn’t say about them. For cinephiles in such a state of inquiry, that cinematic trace of the world of their parents before they were parents... the world of your grandparents before they were grandparents, is a silver screen sieve to the honest heartache and trauma that the country was facing before Reagan’s Morning in America beckoned the age of cocaine and cable.

Within these films lies a minefield of information on what we ignored, often directly, publicly ignored from the lessons of the 1960s.

This goes for much of the world of course, not just the United States. Except that by 1977, the brief period in American commercial cinema that saw movies made for world-weary, working adults had all but been given the death knell, or at least put in the retirement home (Keep the costs down and let the residents put on a show!).

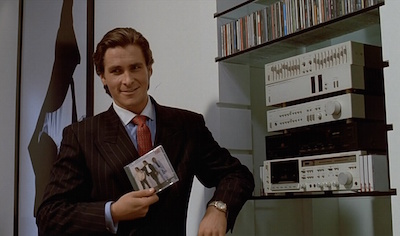

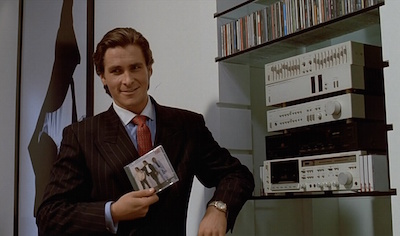

And so we come to the third theme of what I’ve been watching in recent months. I have been revisiting my own childhood and teenage years -- the 1990s and 2000s -- often watching films I had never seen before. These include both English and foreign language works: Alejandro Amnebar’s soapy and serious Thesis. Alex Proyas‘ goth revenger The Crow; Sam Raimi’s Darkman, a man-is-monster adapation of a comic that never existed; American Psycho (pictured), Mary Harron’s seismic bro satire. Then there was pretty much everything by Peter Jackson, including a long over due revisit with the masterpiece that is BrainDead. Heck I even made an honest attempt to rewatch Paul W.S. Anderson’s Mortal Kombat from 1995. When comparing these films to the common vibe of the earlier works cited, this is indeed a very, very different set of films.

So it is here where a curious thread between these two eras began to emerge in my thinking.

If we are to go off of one of Marx’s most famous bits about history repeating first as tragedy and then as farce, one could look at the cinema of the 1970s, and in particular American cinema, as tragic... as living with, learning to cope with a society in denial.

If we are to go off of one of Marx’s most famous bits about history repeating first as tragedy and then as farce, one could look at the cinema of the 1970s, and in particular American cinema, as tragic... as living with, learning to cope with a society in denial.

We begin to morph into farce with the early super hero and fantasy films. This begins with titles we don't even need to blink to remember, hits truly uber farce by the 1990s, my decade, and is, in a commercial sense, the element that still grinds the millstone of the major movies today.

The link I am catching here, the thread at the heart of all this, is the need for artists to recognize hard truths from past eras: markers that were laid out by predecessors, and, in large measure, ignored or forgotten en masse, perhaps in part because we were so busy enjoying the spectacle of it all.

Watching Forman tackle parental inability, generational divides, the mind and emotions of youth and a dozen other topsy turvy little stingers in Taking Off, I truly wondered what my own parents were thinking and feeling during the vector of American Decline and Radicalism.

I've asked them about it. Both have stated something shifted in their thinking during the aftermath of JFK's death in November of '63. As I am sure was the case for most American children about seven or eight years old at the time, a door opened for the both of them... or perhaps it was a window... to a larger world, a world of adult pain and conflict.

My parents were raised by Billy Graham’s Jesus Christ, Television (Batman and Cronkite) and The Bobbsey Twins. They lived for bike rides and the seemingly endless woods that bordered their homes in Maine and Maryland.

I was an indoor kid, raised by whatever art I chose for myself: comic books, movies, radio dramas, science fiction.

In the fall of 1974, my parents both departed for New England and college, where they would eventually meet, becomes friends, date and marry by the age of 23 in 1979.

Here is a snapshot of top grossing, critically praised and cult films released in 1974 America:

The Godfather Part II. The Conversation. Blazing Saddles. Young Frankenstein. The Towering Inferno. The Taking of Pelham 123. Chinatown. Earthquake. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The Paralax View.

Any cinephile can read that as short-hand for a country that was right in the middle of a tragic-farce two-step.

In the fall of 2001, I took the Metro bus and train across the Washington D.C. metropolitan beltway to attend two film courses at a community college... a community college like any other in America, built for the anonymous learner, caught in the twilight of the middle class.

2001 was the first time in the history of the cinema where two films grossed more than $800 million dollars world wide. The films in question are Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

With X-Men, Batman, Superman, and now wizards and witches and elves making their way to the big screen, embraced wholly by just about everyone it seemed, farce had come to ransack our childhoods. Or at least those white masculine childhoods. Indeed, the geeks (liberal-minded technophiles and indoor kids; mostly men who had yet to outlast a stigmatic image of nerd propelled by the alpha male) had inherited the earth with their created worlds. Their fantasies.

At their best, at their truest, these works were complex and engaging reflections of our world. They were, philosophically and emotionally, descriptive works for our society. They were, in short, great stories... parables, allegory, metaphors, satires... a circus, a spectacle... a madman arena the cinema always seemed to readily stumble into.

In the global world America found itself in post 9/11, our canvas for the cinema had to match our canvas for real life conflict at an even greater length. That canvas was stretched far and wide, further than it ever had before. Hollywood was no longer an American mindset.

War, wherever, and of all stripes, proxy or cultural, kept up its hustle with a little more noise than usual.

If Vietnam made America a nation of Television watchers, the second war in Iraq - provided by the son of the father of the first -- made the audience weary of anything but winning and even winning itself. Barack Obama became president. That was considered a win. Donald Trump wanted to win and apparently other people wanted him to win, too.

And so it is that the farce of reality outshines the farce found in films.

Yes, indeed, 2018 is the year Steven Spielberg released his adaptation of a book whose very foundation is built upon the pop cultural rigging of the blockbuster auetur’s early works.

In contrast, most filmmakers live today with iPhones in their hip pockets. A digital cultivation of sustainable communities for creators begins behind the fingertips and on screen.

As always, we live in a curious moment. Perhaps, we’d like to believe an extra curious one.

By looking back at the cinema of my parents’ young adulthoods, a cinema that explored the lives of lost parents and children, the birth of neoliberal hypocrisy,... a society in great flux... I begin to gain insight into what we were collectively beginning to ignore at the time.

The kinds of bonds I’ve been discussing, at least through a conflict lens, can often be wrought in tragedy. We’ve recently seen it in the blistering nightscapes of Josh and Benny Safdie’s Good Time;The cool malaise of Malik Vithal's Imperial Dreams; the sunbaked backs and inner thigh sweat of the teens in Andrea Arnold’s American Honey. If you turn a page to low-budget cinema, intelligence, anger and compassion reign in Nathan Silver’s Uncertain Terms, while true DIY works like Perry Lang’s They Look Like People plays it candid with the complexities of the male psyche in flux. We get farce and tragedy mixing it up with Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You, Daniels’ Swiss Army Man or the cherry on top that is Rick Alverson’s Entertainment.

And isn’t Thor: Ragnarok somewhat making fun of itself for existing at the expense of... gosh, how much money exactly?

If the narrative of the white man is changing its tune for the better, or else entirely breaking down for good, it makes sense to me that we souls, in a highly instant and meta world, want it as tragedy (remember that dangerously toxic and straight-laced films like the Death Wish remake are also viewed as tragedy by the right audience) and most certainly as farce and! if Netflix has their way, any niche in between...

I pause to look at my current favorite films of the year. There’s the British Paddington 2, a sequel to a children’s film about a compassionate, anthropomorphic bear cub who loves marmalade sandwiches. Then we have Josephine Decker’s marvelously strange and soul-shaking Madeline’s Madeline; a film that could have easily fit into the wilds of American cinema circa 1970. We also have that aforementioned Spielberg on virtual Spielberg feature.

I pause to look at my current favorite films of the year. There’s the British Paddington 2, a sequel to a children’s film about a compassionate, anthropomorphic bear cub who loves marmalade sandwiches. Then we have Josephine Decker’s marvelously strange and soul-shaking Madeline’s Madeline; a film that could have easily fit into the wilds of American cinema circa 1970. We also have that aforementioned Spielberg on virtual Spielberg feature.

It is 2018. The very poster child for modern populist cinema has come full circle in his career.

It is 2018. J.J. Abrams is probably not the new Berg. It is likelier that it is Ryan Coogler. Perhaps it is Marvel super producer Kevin Feige pulling the strings... or rather... even before a woman... no-body... a neural network playing with silver screen ghosts in the digital dark, rearranging past lives to fit new forms behind your sleeping eyelids.

It is 2018. It is a Friday night. I arrive at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre, a few blocks east of the Dolby where the Oscars are held. Before the Chinese was built, the Egyptian is where Grauman’s Hollywood kept their red carpets. The building is designed to specifically look like an ancient temple.

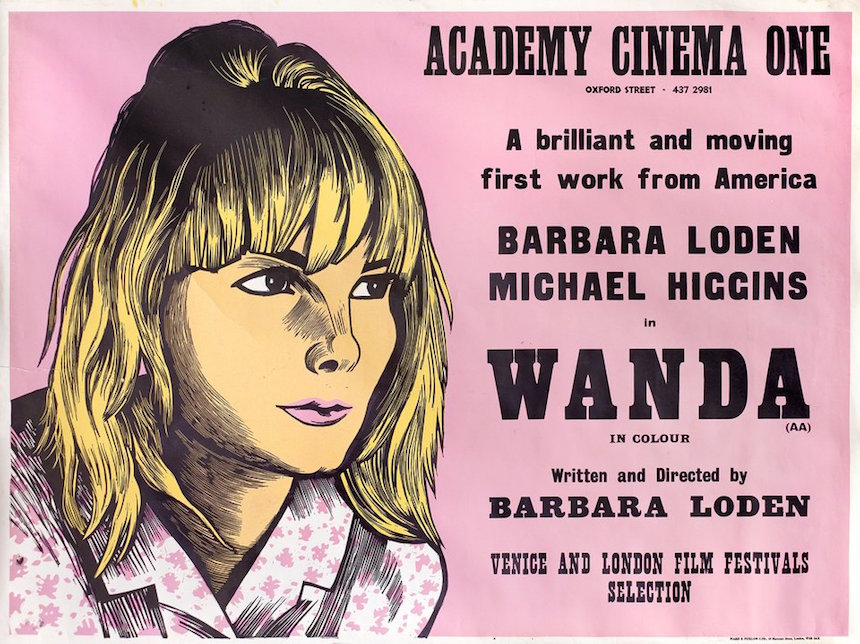

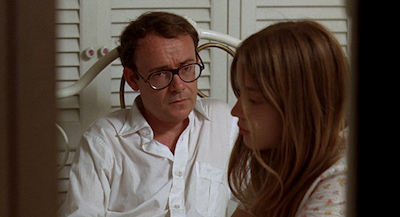

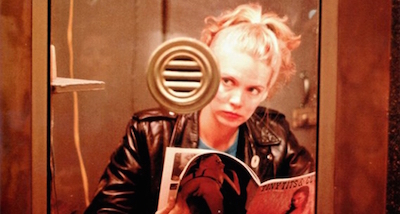

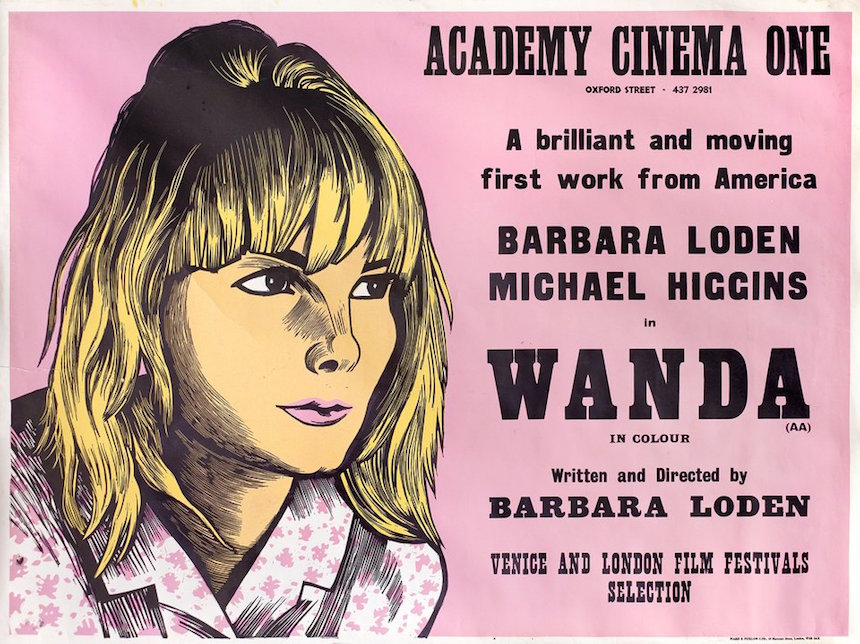

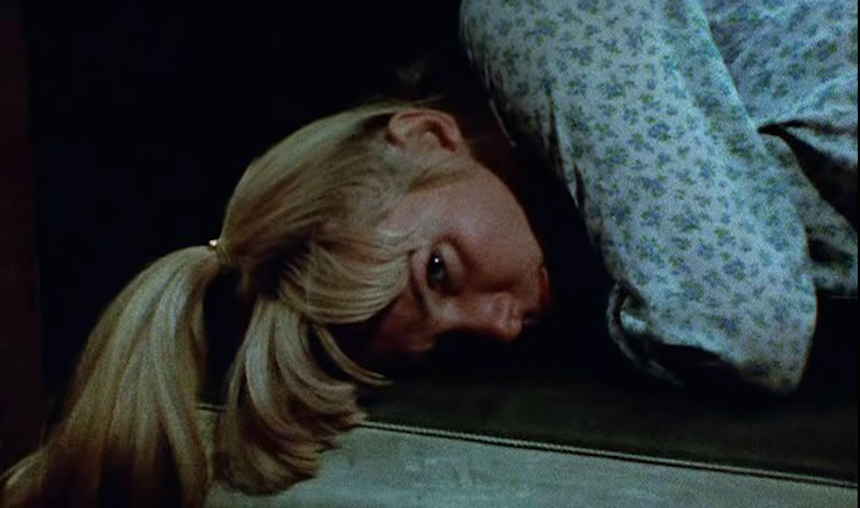

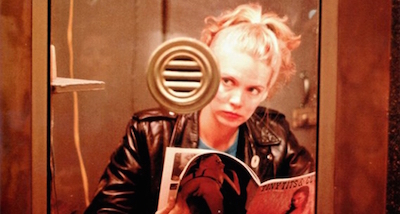

I am here to see the new restoration of Barbara Loden’s Wanda, a winner of the Venice Film Festival in 1970, and a groundbreaking work of Americana realism to rival Easy Rider and Two-Lane Blacktop. It is Loden’s only feature film.

Tommy Wiseau’s overblown cult hit The Room is playing once again in the main theatre. It has 616 seats. For screenings I've attended that do not feature special guests, it is typically a third full. Wanda is playing in the smaller theatre. This room is named after Steven Spielberg. It has 77 seats. Wanda is sold out. There is a stand-by line. As it grows, an employee of the Cinematheque steps outside, looking a bit frazzled at the ballooning crowd of cinephiles on the doorstep.

Perhaps they made a mistake booking Wanda in the Spielberg.

With, retrospectives, restorations and streaming, the films from this group directed by women have been gaining proper attention this past decade by cine-literate millennials and the back edge of GenXers, curious as to the world that existed in the years building up to their birth. My generation is like any other. They are hungry for some notion of "life before" and what that does and doesn’t say about them. For cinephiles in such a state of inquiry, that cinematic trace of the world of their parents before they were parents... the world of your grandparents before they were grandparents, is a silver screen sieve to the honest heartache and trauma that the country was facing before Reagan’s Morning in America beckoned the age of cocaine and cable.

With, retrospectives, restorations and streaming, the films from this group directed by women have been gaining proper attention this past decade by cine-literate millennials and the back edge of GenXers, curious as to the world that existed in the years building up to their birth. My generation is like any other. They are hungry for some notion of "life before" and what that does and doesn’t say about them. For cinephiles in such a state of inquiry, that cinematic trace of the world of their parents before they were parents... the world of your grandparents before they were grandparents, is a silver screen sieve to the honest heartache and trauma that the country was facing before Reagan’s Morning in America beckoned the age of cocaine and cable.  If we are to go off of one of Marx’s most famous bits about history repeating first as tragedy and then as farce, one could look at the cinema of the 1970s, and in particular American cinema, as tragic... as living with, learning to cope with a society in denial.

If we are to go off of one of Marx’s most famous bits about history repeating first as tragedy and then as farce, one could look at the cinema of the 1970s, and in particular American cinema, as tragic... as living with, learning to cope with a society in denial.

I pause to look at my current favorite films of the year. There’s the British Paddington 2, a sequel to a children’s film about a compassionate, anthropomorphic bear cub who loves marmalade sandwiches. Then we have Josephine Decker’s marvelously strange and soul-shaking Madeline’s Madeline; a film that could have easily fit into the wilds of American cinema circa 1970. We also have that aforementioned Spielberg on virtual Spielberg feature.

I pause to look at my current favorite films of the year. There’s the British Paddington 2, a sequel to a children’s film about a compassionate, anthropomorphic bear cub who loves marmalade sandwiches. Then we have Josephine Decker’s marvelously strange and soul-shaking Madeline’s Madeline; a film that could have easily fit into the wilds of American cinema circa 1970. We also have that aforementioned Spielberg on virtual Spielberg feature.